NEW-YORK — Kazakh civil society organizations took center stage at the third Meeting of States Parties (3MSP) to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) on March 3-7, urging the United Nations (UN) to act for nuclear-affected communities. The delegation delivered powerful statements and policy recommendations, calling for global commitment to justice and disarmament.

3MSP TPNW. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

Advocating for nuclear justice

In collaboration with the Steppe Organization for Peace (STOP), the Friedrich Ebert Foundation (FES) Kazakhstan, the Center for International Security and Policy (CISP), Committee Polygon 21, and international organizations, Qazaq Nuclear Frontline Coalition (QNFC) organized panel discussions, documentary screenings and forums, amplifying the voices of nuclear-affected communities.

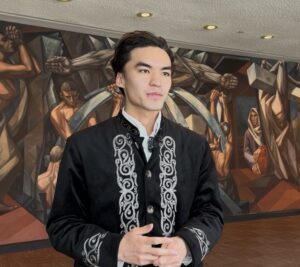

Yerdaulet Rakhmatulla, the QNFC co-founder. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

Yerdaulet Rakhmatulla, the QNFC co-founder, highlighted the coalition’s mission at the 3MSP, emphasizing the significance of independent civic engagement.

“Our alliance brings together civil society leaders and affected communities in Kazakhstan. We work on principles of intergenerational and transnational solidarity,” said Rakhmatulla.

They also prepared a working paper which details the long-term humanitarian and environmental impact of over 400 nuclear tests at the Semipalatinsk Nuclear Test Site between 1949 and 1989. The paper provided policy recommendations on victim assistance, environmental remediation, and international cooperation, advocating for an inclusive approach to nuclear justice.

Rakhmatulla noted that this is also the first time the Kazakh community has delivered a high-level statement at the UN Trusteeship Council.

Statement: Call for action on survivor assistance

QNFC co-founder Aigerim Seitenova delivered the statement on March 4, urging international stakeholders to address the enduring consequences of nuclear testing.

QNFC co-founder Aigerim Seitenova delivered a statement on March 4, urging international stakeholders to address the enduring consequences of nuclear testing at the 3MSP. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

“We stand in solidarity with all the nuclear-affected community members across the world and applaud our common resistance and resilience in pursuing nuclear justice and a nuclear-weapons-free world. It was never our choice to be guinea pigs of the nuclear experiment and exploitation for the sake of the arms race. But it is our determination now to advocate for nuclear justice,” said Seitenova.

The statement emphasized the urgent need for Kazakhstan to modernize its legal framework on victim assistance and compensation. A nationwide survey conducted by QNFC found that over 500 respondents from nuclear-affected regions called for legislative reforms to improve healthcare accessibility, provide free medical treatment for radiation-related illnesses, and implement universal screening programs for survivors.

“For decades, our communities were deliberately excluded from discussions while being subjected to severe harm without our knowledge and consent. This moment presents a critical opportunity to rectify historical injustices through concrete measures of redress,” said Seitenova.

On behalf of the coalition, she urged TPNW states to establish an international trust fund to support those impacted by nuclear weapons. She emphasized that the fund must be inclusive, transparent and survivor-centered, with affected communities and civil society having equal voting rights alongside states.

A fight for recognition and survivor-centered policymaking

Kazakh advocates also discussed grassroots efforts in disarmament, addressing governance gaps, financial constraints and survivor-centered policymaking. Alisher Khassengaliyev, a founding member of STOP and operations coordinator for Youth for TPNW, noted that Kazakhstan’s survivor assistance policies remain fragmented and underfunded.

“The 1992 law on social protection of nuclear test survivors established a framework for survivor assistance, but its implementation has been severely limited by budgetary constraints and the absence of long term financial commitments survivor benefits, medical services and environmental remediation efforts often suffer from inconsistent funding living affected communities without the sustained support they need,” said Khassengaliyev.

STOP founding members Alisher Khassengaliyev (on the left) and Adiya Akhmer (on the right). Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

“If it relies solely on voluntary contributions, it risks becoming another unpredictable mechanism that struggles to meet survivors’ needs over time. To prevent this, the trust fund must be structured around multi-year financial commitments, rather than short-term pledge,” he added.

Khassengaliyev proposed establishing a survivor and civil society advisory board within the TPNW trust fund to ensure affected communities have a direct voice in shaping funding priorities. He noted that survivors must be active decision-makers, rather than passive recipients of aid.

“Nuclear justice is the effort to acknowledge, address and remedy the harms caused by nuclear weapons—ranging from environmental destruction to long-term health impacts—while ensuring that affected communities are at the center of decision-making about their futures,” said Adiya Akhmer, STOP founding member and independent researcher.

She noted that these communities continue to suffer from displacement, trauma and severe health consequences that persist for generations. This collective harm is also deeply gendered, disproportionately affecting women and children. Achieving nuclear justice means acknowledging and addressing these injustices while implementing concrete remedies that account for the specific vulnerabilities of those most affected.

Indira Weavor, peace activist and QNFC member. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

“One of the leading voices in the movement against these tests was the renowned poet Olzhas Suleimenov. He led a truly historic movement against nuclear testing, particularly after illegal gas leaks occurred in Chagan strategic airbase [in Semiplatinsk],” said Indira Weavor, peace activist and QNFC member.

“The Nevada-Semipalatinsk international anti-nuclear movement became the fastest-growing initiative in the world. It united people across nations and continents. The impact of this movement is, was and still is of huge historic significance,” she added.

It directly prevented 11 of the 18 planned tests in 1989, the final of which occurred in October of that year. The Semipalatinsk test site closed on Aug.29, 1991.

“I was born in 1977. I am one of three sisters, and I consider myself fortunate that I have not experienced any major health issues—though I have never undergone specific medical testing for radiation exposure. As a mother of two boys, I often wonder how this legacy might affect my children,” she said, noting the need for continued research, awareness and international commitment to nuclear disarmament to prevent future generations from bearing similar uncertainties.

Raising awareness among the youth

The audience watching Seitenova’s “Jara” which explores the gendered impacts of nuclear testing, sharing the experiences of women who have endured radiation exposure. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova/ The Astana Times

Discussions at the UN also underscored the need to educate and engage young people on nuclear disarmament. A survey presented by Medet Suleimen, program officer at FES Kazakhstan, revealed that while 80% of Kazakh youth support the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), a significant percentage still view nuclear weapons as essential for security.

“This highlights the importance of forums like this, which should play a role in educating young people and countering misinformation. Kazakhstan should consider hosting another international conference on nuclear security to build on these discussions,” said Suleimen.

Rakhmatulla echoed this sentiment, stressing the importance of long-term studies to track young people’s perspectives on nuclear disarmament.

“By investing in their leadership, we will see more young voices emerge as advocates for nuclear justice and policy change,” he said.

Documenting the nuclear legacy

The UN events also featured the premiere of two Kazakh documentaries—“I Want to Live On” and “Jara” (Wound)—which shed light on the enduring consequences of nuclear testing.

Directed by Alimzhan Akhmetov (at the front) and Assel Akhmetova, “I Want to Live On” presents testimonies from survivors of the Semipalatinsk nuclear tests. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

Directed by Alimzhan Akhmetov and Assel Akhmetova, “I Want to Live On” presents testimonies from survivors of the Semipalatinsk nuclear tests, revealing the long-term health and environmental impact. The full 40-minute version premiered at the UN as a side event co-organized by Kazakh permanent mission to UN, Soka Gakkai International (SGI) and CISP on March 3.

Seitenova’s “Jara” explores the gendered impacts of nuclear testing, sharing the experiences of women who have endured radiation exposure. Through self-exploration and six testimonies from women in nuclear-affected regions, the film explores the gendered impacts of radiation, including gender-based violence, the social and cultural consequences of technocratic governance and militarization, and the roles and leadership of women within their communities.

The film creates a space for nuclear-affected communities to share their stories without victimization or exploitation.

Speaking after the screening, Seitenova shared plans to present the film at Harvard University on March 13, followed by a possible European tour in Berlin, Geneva, Vienna, Paris and London.

Danity Laukon, a nuclear justice advocate from the Marshall Islands. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

“This is not just a political or academic discussion—it is deeply personal. By sharing their pain, the women in this film tell a heart-wrenching testament to the collective suffering of millions harmed by nuclear tests.”

The screening resonated with audience members, including Danity Laukon, a nuclear justice advocate from the Marshall Islands, who drew parallels between Kazakhstan’s nuclear legacy and the experiences of her own community.

“Sickness, cancer, fighting, radiation – these words are not unfamiliar to me. In the Marshall Islands, we endured 67 nuclear and thermonuclear tests from the U.S. nuclear testing program. Many of the experiences of these women from Kazakhstan mirror the struggles of our own women,” said Laukon.

“Women in my country gave birth to what they called ‘jellyfish babies’—infants who were deformed, moving, with a heartbeat, but not human. This caused immense psychological and social trauma. I connected deeply with the women in the film on that level. I truly admire their strength. It is not easy to tell these stories,” she added.

Committee Polygon 21 co-founder Maira Abenova (on the left) and Yerdaulet Rakhmatulla, the QNFC co-founder. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

Following the screening, Committee Polygon 21 co-founder Maira Abenova, who is also featured in the documentary stressed that nuclear injustice did not end with the closure of Semipalatinsk test site and that global efforts must prioritize survivor assistance, policy reforms, and the strengthening of international disarmament mechanisms.

“We live in troubling times. The world is once again teetering on the brink of global conflict and today we are not just here to discuss, we are here to act,” said Abenova.

“Thousands of people were affected, and many have walked away before justice was served. But our struggle is not just about the past—it is about the future,” she added, calling for increased international cooperation, accountability from world leaders, and the establishment of a trust fund for nuclear survivors.

“We have already achieved the closure of the Semipalatinsk test site once. We will continue to fight because a world without nuclear weapons is not a utopia, but a necessity,” said Abenova.