ASTANA – One month before the parliamentary election in Kazakhstan, political engagement has reached an unprecedented level, the result of changes the nation has implemented over the past year and a half.

Almaty. Photo credit: shutterstock.com.

The past two years have been increasingly eventful for Kazakhstan’s political life, with constitutional changes and elections following one after another. The nation voted for constitutional amendments that changed nearly one-third of the country’s basic law on June 5. Six months later, the citizens voted in the presidential election on Nov. 20, which saw incumbent Kassym-Jomart Tokayev garnering 81.2 percent of the votes.

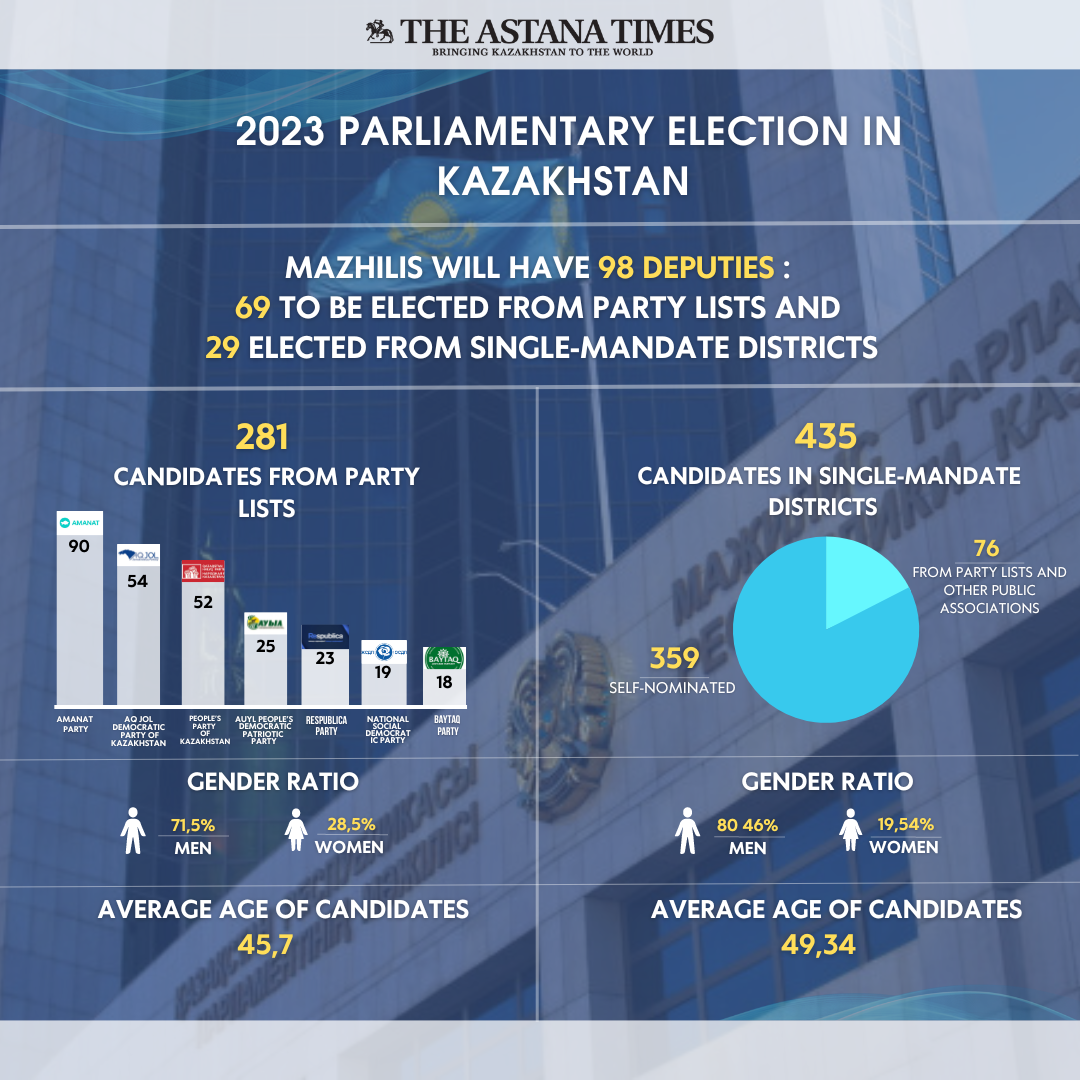

On March 19, Kazakh citizens will head to the polls to vote in the elections for the Mazhilis, the lower chamber of the Kazakh Parliament, and the maslikhats, local representative bodies. The competition is going to be fierce, with 283 party list candidates and 435 single-mandate candidates for the Mazhilis.

Kazakhstan will have election to the Mazhilis on March 19. Photo credit: The Astana Times

In a Feb. 8 interview with the Kazahstanskaya Pravda newspaper, Andrei Bodrov, a Ukrainian political consultant with 25 years of experience conducting election campaigns in Ukraine and other post-Soviet countries, emphasized the growing democratization of public life and the revival within the political field of Kazakhstan.

“When talking to voters, I notice that people often do not even know who their deputy is. And now they get their own representative – a specific person, whom they can address and solve issues, and whom they can ask personally. This contributes to easing social tension and the fact that the politicians become more responsible,” said Bodrov.

He sees the significant impact of the mixed proportional-majoritarian electoral system on this process. Stemming from last year’s constitutional changes, out of 98 deputies in the Mazhilis, 29 are to be elected from single-mandate constituencies, where citizens, given that they meet the necessary requirements, can self-nominate themselves.

Andrei Bodrov. Photo credit: apkpolit.tech.

Bodrov also sees a correlation between rising political competition and higher accountability among politicians.

“In the conditions of political competition, people who will not take care of their electorate will simply cease to be in demand. Accordingly, this seriously reduces tension, increases the personalization of responsibility and consequently, improves the quality of politics itself,” the political expert said.

Easing social tension is particularly paramount in Kazakhstan, one year after the tragic January events sent the country into turmoil.

“I believe this moment [January events] was critical. You saw how precarious peace is in society and how it should be protected. In Ukraine, unfortunately, it was not [preserved]. The tension in the ethnic and religious areas, stirred up by politicians in their electoral interests and heated up by outside players, has led to sad and terrible events,” he said, commending how Kazakhstan has maintained peace and stability between the ethnic groups within the country.

Civil society continues to grow in Kazakhstan

The expert noted the increased civil society participation, commending a well-developed system of public organizations, councils, and advisory bodies.

“Of course, I have heard comments about their decorative nature, but they are still social lifts, opportunities for self-fulfillment for a whole range of public leaders, primary responses to the request for participation in decision-making. People go and do something – useful for themselves and society,” he said.

He said it is “absolutely normal” when people choose to stay out of politics. “If everyone were a potential leader, we would have destroyed each other long ago,” he added.

Parliamentary election as a chance to involve people in decision-making

The March 19 election will take place earlier than scheduled. Bodrov said it is a common practice worldwide, as a “new mandate of trust is needed under the new system.”

“There is an attempt, on the contrary, by democratizing the political field, to increase grassroots activity and encourage people to be more informed, more responsible. The authorities seek to share responsibility with citizens. And the President has the opportunity tomorrow to say, ‘you voted for this, you elected these people, so their actions are taking place with your approval’,” he said.

The key goal of the election is to “legitimize power,” but legitimacy is more than that. “It is a matter of social trust,” he added.

One of many other changes in the upcoming election is the inclusion of an against-all option, which, according to Bodrov, offers an opportunity to engage a group of the population who otherwise does not have a motive to go to the polls.

“Let those who feel that they need to speak out come forward and do so, and the introduction of the ‘against all’ option will encourage them. The percentage of those who vote this way is an important indicator of dissatisfaction with the quality of decisions made, a crucial indicator for the authorities, and an opportunity to reduce social tension,” said the expert.

Political parties in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan has seven political parties, and two of them, Baitak and Respublica, achieved registration following the simplification of party registration procedures.

“Ukraine has 365 political parties, and this has not been very successful. The United Kingdom and the United States do well under a two-party system. In this case, we have as many as we need now,” he added.

The party’s essential goal is not to gather people who are “eager for power” but rather to reflect the hopes of a certain core segment of the population. The goal is to communicate with them and make sure their needs and demands are part of the political agenda going forward .

“The core of the party should be people who can come to the people, put forward the ideas they like, gain their trust and support them for five years. Single-mandate candidates are fully dependent on the voter, unlike those who run on a list and are heavily dependent on the party’s top leadership,” he said.