LONDON – Oxford University scholars use Kazakh and Malay proverbs in pedagogical approach for storytelling about sustainability. Olga Mun, a doctoral researcher at Oxford University from Kazakhstan, and Aizuddin Mohamed Anuar, a writer and lecturer at Keele University from Malaysia, developed an arts-based project based on the analysis of traditional proverbs on environmental responsibility, economic efficiency and social solidarity.

Aizuddin Mohamed Anuar, Olga Mun, and Molly Drummond, a U.K.-based zine artist. Photo credit: Olga Mun.

“While the global community is impacted by climate change and many initiatives have the potential to address them, the Global South countries are persistently painted in a deficient light and in need of rescuing. However, our educational project shows that communities in Malaysia and Kazakhstan historically had a wealth of knowledge on sustainable living,” said Mun in an interview with The Astana Times.

With master’s and doctoral degrees from Oxford University and work experience in corporate philanthropy, Anuar is focused on comparative and international education. As for Mun, epistemic injustice in higher education across national borders is the main research interest. She is a co-convenor of the Philosophy of Education Reading Group at the Oxford University Department of Education.

Mun and Anuar researched more than 30 books and scientific works about proverbs in Kazakhstan and Malaysia. Funded by the Institute for Sustainable Futures at Keele University, the work resulted in the publication of a zine (short for fanzine), a small amateur-produced magazine most associated with popular cultures or related to a specific subject.

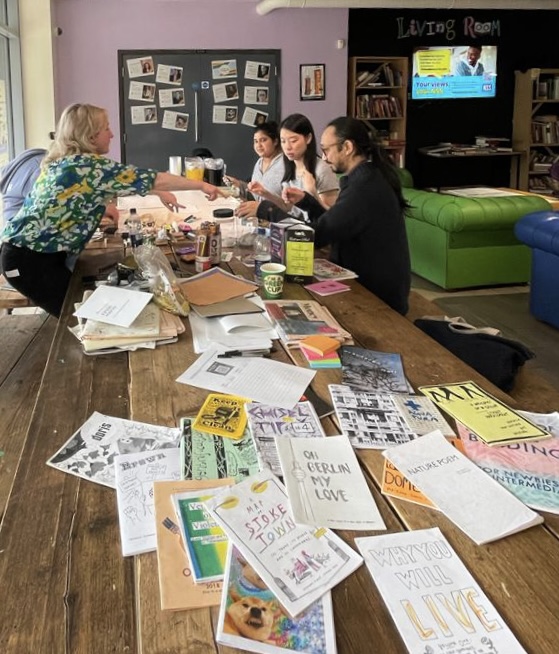

The process of zine-making. Photo credit: Olga Mun.

The zine, which was published this July, is called “Telaga Zher.” The title proceeds from the combination of Malay and Kazakh words – “telaga” in Malay means “well” or the “water spring,” and “zher” is translated from Kazakh as “soil.”

A zine-making workshop at Keele University was the major workspace for the scholars. In London, they visited the Stuart Hall Library, the special collection at InIVA (Institute of International Visual Arts), and Housmans Bookshop, the longest-running radical bookshop in the United Kingdom, to study zines from all over the globe and address the range of interests and audiences.

Explaining the uniqueness of the zine, Mun noted that “rooted in traditions of dissent such as antiracism, feminism and punk culture, they may serve as a critique of contemporary knowledge production divorced from crises outside the comfort of the ivory tower.”

“Unlike academic books and articles, zines are affordable to publish and distribute,” she added.

A zine-making workshop at Keele University. Photo credit: Olga Mun.

Overall, they have collected 30 proverbs on the three key topics – economy, society, and environment. The work is still in progress.

Kazakh proverbs contain interesting examples of collective wisdom – since ancient times, people have known how to live in harmony with nature.

“Sustainability knowledge in proverbs predates the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),” said Mun.

The proverbs highlight the importance of fostering social inclusion, long-term planning, resource management, and environmental protection. They represent the fundamental part of present-day law and ethics.

Many Kazakh and Malay proverbs focus on the human ability to use natural resources without undermining the integrity of ecosystems to reduce the burden on the environment. For example, one of the Malay proverbs says that nature expands to become a teacher – “alam terkembang jadi guru.”

The Kazakh proverb “būlaq bolmasa, özen bolmas edı” is translated as “if there is no spring (a source), there would be no river.” In that sense, even a small well can become the origin of a larger environmental flourishing. Another proverb “kün ortaq, ai ortaq, jaqsy ortaq” says that sun, moon, and kindness are infinite resources available for everyone.

Living in a low-resource setting should not be embarrassing and pursuing a wealthy lifestyle does not provide a human being with superiority. This is the meaning of the Kazakh proverb calling for equality – “joqtyq ūiat emes, toqtyq mūrat emes.”

“Students and colleagues were very curious to learn about the project and reached out to use the zine in the British higher education context. At the risk of not being humble, the project turned out to be a great hit with the students. Some are working on their own zines and are staying in touch. For others, it was their first encounter with Kazakh culture. I am happy it was a positive one,” said Mun.

The project’s idea originated from the overlap of Mun’s and Anuar’s interests in knowledge passed down through generations in the form of proverbs. Traditional sayings represent a vital part of Kazakh and Malaysian cultural heritage, reflecting the wisdom of people.

“We are very familiar with the theories coming from the Global North contexts. Zine pedagogy through our project is utilized to suggest the potentials of educating for sustainability within and beyond the academy by foregrounding global epistemic diversity and an arts-based approach to knowledge production and dissemination,” said Mun.

According to the zine, “people are living in a world with challenges associated with climate change, widening inequality, the curtailing of democracy, and social isolation despite increased connectivity.” Proverbial wisdom can help people reimagine ways of tackling contemporary problems in the hope of living more sustainably.