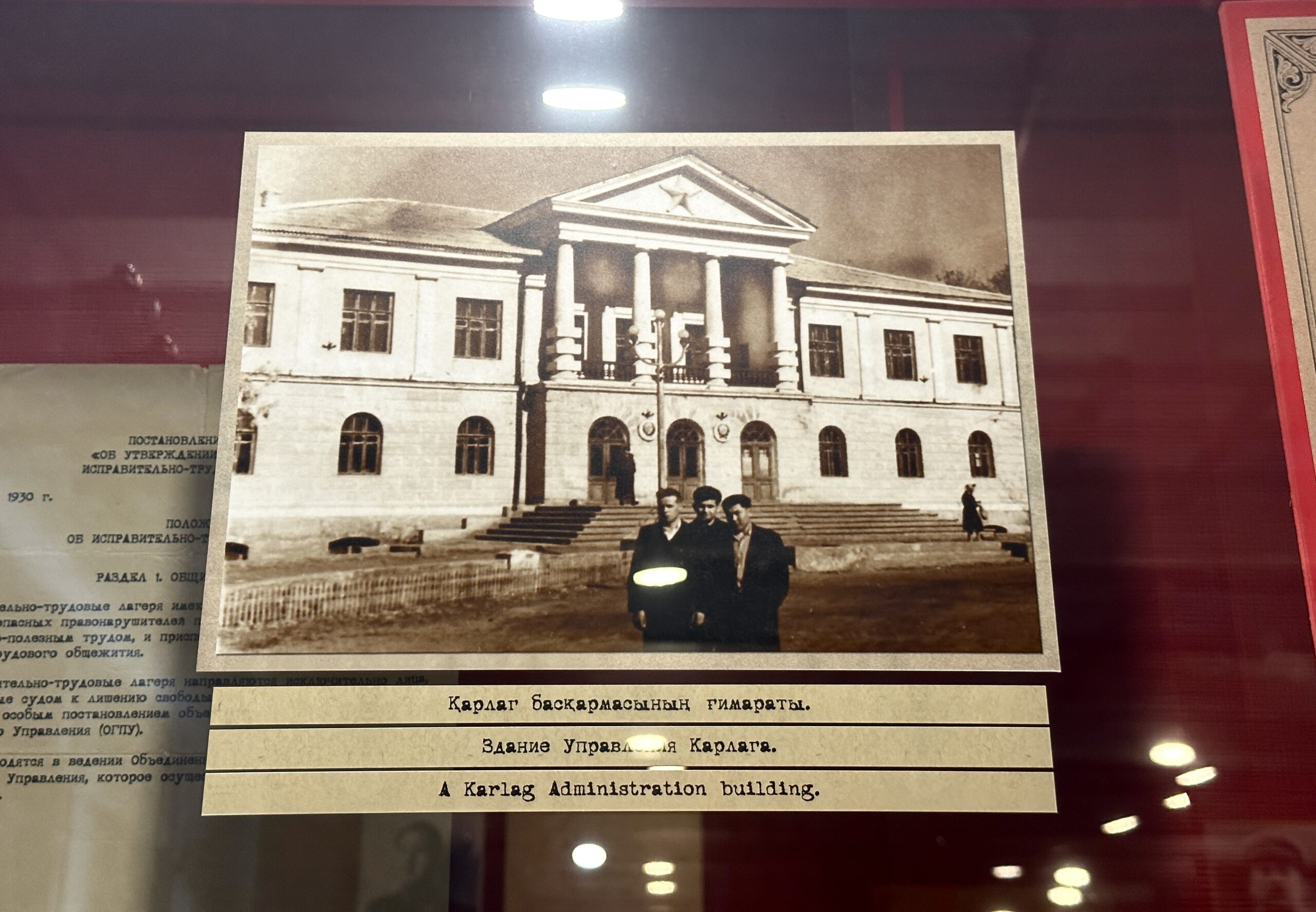

KARAGANDY REGION – The museum of memory of victims of political repressions, known as Karlag (Karagandy corrective labor camp) museum, is housed in the original administrative building of one of Joseph Stalin’s largest Gulags (Main camp administration). The museum memorializes the victims of political repressions that took place in the 1930-1950s in Kazakhstan. It is a sobering reflection of the horrors of an unchecked regime.

Karlag museum is housed in the original administrative building of one of Joseph Stalin’s largest Gulags in the Karagandy Region. Photo credit: Aibarshyn Akhmetkali/The Astana Times

Falling under the dark tourism category, the Karlag museum is a tragic history of the Soviet past, a system of labor camps, which claimed and displaced millions of lives.

Today, the museum preserves the historical heritage not only of the region but of the Soviet gulag system with the aim to educate the world about how far a regime can drift from the path of human rights.

Society cannot learn from history unless this history is learned, tour guide Yelena Pystina said as she started the tour for a group of media representatives on July 23 organized by Kazakh Tourism national company.

“Karlag is a memory for the sake of the future. Such things cannot be forgotten, as we have no right to repeat them,” she said.

The history of Karlag

The guide points to a large layout of a watchtower with grids and barbed wire placed against the wall.

“Such watchtowers stood all around the perimeter of the camps and a guard was stationed there 24 hours a day. Our tower is against the background of Stalin’s portrait. Stalin is painted in such a way that no matter where you go, it will seem that he is watching you,” Pystina said.

Archive photo of the Karlag administrative building. The building remains largely unaltered up to this day. Photo credit: Aibarshyn Akhmetkali/Karlag museum

Karlag camps were first established on Dec. 19, 1931, in the Dolinka village, which is 40 kilometers from the city of Karagandy.

Overall, 478 camps were established on the territory of the Soviet Union as part of the gulag network. With 26 branches and 192 camp points, Karlag was one of the largest local concentration camp networks spread across a vast area.

“Karlag covers a distance of 300 kilometers from north to south and 200 kilometers from east to west. Along with this region, there is also the Akmolinsk branch in the north, as well as Balkhash and Zhezkazgan branches. Its territory combined with its branches and arable lands is equivalent to the size of modern-day France,” Pystina explained.

“Around 4,000 Kazakhs and 1,200 families of other nationalities used to live on the site of the future camps. All were forcibly evicted from their places,” she added.

The Karlag museum is located in the main administrative building of the camp, which opened its doors in 2011.

The museum recreates a copy of a labor camp interior, replete with solitary confinement cells, torture rooms and barracks.

The main exhibit of the museum is the building itself, said Pystina. “The building remains largely unaltered.”

Living conditions inside

A corridor full of turnstiles, displaying real inmates’ personal files, is another reminder of the horrors of those years.

Over one million prisoners passed through the Karlag over the years of its existence.

Torture room. Thirty-one types of torture took place in Karlag. Photo credit: Aibarshyn Akhmetkali/The Astana Times

Living conditions in the camp were severe. Hard labor conditions and malnutrition afflicted most people in the camps.

“Prisoners lived and worked in the barracks, which were long one-story buildings. Most often they were built from saman (adobe), which is a mixture of clay, dung and straw. The furnishings in the barracks were very primitive. Benches, roughly chipped tables, sometimes stools or nightstands, and work equipment in the workers’ barracks,” Pystina said.

One striking area is an original pit built in the building. Although no documents remain that explain the purpose of this pit, the guide believes it was likely used for torture.

A pit supposedly built for torture. Photo credit: Aibarshyn Akhmetkali/The Astana Times

“This is a very ancient form of punishment. In the East and the Caucasus, such pits are called ‘zindan’. These pits were not deep. You could only sit in them. Cold water was poured at the bottom to increase the dampness. The prisoner would receive only 100 grams of bread and a glass of cold water a day. The bars were closed. The prisoner stayed in the pit for two or more days. Then he would come out broken, both morally and physically,” Pystina explained.

Conditions inside shared men’s and women’s cells were dire as well. To counter the monotony of the cells, women used to decorate them with hand-made paintings or embroidery.

“The women tried to keep the cells tidier and to decorate them in some way. These paintings were made by hand by female prisoners,” said Pystina.

No less frightening are the investigator’s office and the torture room.

“Thirty-one types of torture took place in Karlag. We know about torture from the memoirs of [Russian writer] Aleksand Solzhenitsyn [who was an inmate at Karlag] and from the notes of the Prosecutor General. The most used types of torture were hot and cold cells. Women were put on high stools to make their legs drain,” said Pystina.

“Tortures were finally abolished a month after Stalin’s death. Whether torture was abolished immediately here we will never know,” she added.

Women and children in the camps

Often overlooked among the victims of Karlag were women and children.

On Aug. 15, 1937, a law on family members of traitors to the Motherland was passed by the Soviet authorities. The law stipulated that all relatives of people who had been convicted of treason or arrested as an “enemy of the people” were also to be arrested and sent to labor camps, including women and children.

Women’s cell. Photo credit: Aibarshyn Akhmetkali/The Astana Times

The most infamous unit for women was the Akmola concentration camp of wives of traitors to the motherland, better known as ALZHIR.

“Several women’s wards were built in Karlag. Women were brought here, sometimes pregnant or with babies. They gave birth locally and the children were sent to orphanages. There were four orphanages on the main territory of Karlag. There were also nurseries and kindergartens built later on,” said Pystina.

“The babies were very poorly cared for and often died. Many of them were buried not far from Dolinka in the Mamochkino (Mother’s) cemetery. This cemetery is now protected by the state. It is looked after by both local residents and the staff of our museum,” said Pystina.

The picture of Stalin and Vyacheslav Molotov (Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs) surrounded by children with the inscription ‘Thank you, Comrade Stalin, for our happy childhood’ next to the empty cradles in the museum is not free from irony.

According to statistics, 924 children died between 1941 and 1944 in Karlag, 114 kids died in 1939, and 1,130 children died between 1950 and 1952. Around 3,000 children born in Karlag survived.

Scientific discoveries

“When the Karlag was established, the government solved three problems. Firstly, it provided food for the new industrial area, because Karlag is primarily an agricultural camp. Secondly, it provided free labor through prisoners. And thirdly, it contained a large number of scientists from many different fields,” said Pystina.

The fact that some of the greatest scientific discoveries emerged from Karlag is often overlooked.

The guide tells gripping stories about the many Soviet scientists who went through the Karlag camp system.

“Alexander Chizhevsky, a famous biophysicist and future Nobel nominee, invented his famous Chizhevsky chandelier in Karlag, which ionizes the air. This contributes to the prevention and treatment of lung diseases. This chandelier was tested for the first time by our miner from Karagandy in 1940,” said Pystina.

Other brilliant scientists who survived Stalin’s purges in Karlag include Anna Lanina, who developed a new breed – the Kazakh white-headed cattle, Igor Fortunatov, who invented many varieties of vegetables and gourds, Vasily Pustovoy, who grew about 40 varieties of sunflowers and other produce.

Prisoners also worked in mines and on railroads. “Among them were a couple of design engineers, Lily Palman and Mikhail Tseturov. They were the only couple who were allowed to marry and live legally here. They converted car engines from gasoline to biogas, which is produced by rotting vegetables, sawdust or manure,” said Pystina.

End of Karlag

Although the labor camps were not closed after the death of Stalin in 1953, the number of inmates was reduced and the degree of state terror was attenuated.

“Karlag was reorganized on June 27, 1959, to be transferred to the Ministry of Internal Affairs. By the end of the 1950s, there were few political convicts in Karlag, the majority of prisoners were criminals,” Pystina informed.

Most of the barracks at Karlag that housed the prisoners have long been destroyed or rotten away.

“Many campsites continue to operate as prisons for actual criminals. They are located on the perimeter of the settlements near Karagandy, including about five around the village of Dolinka,” Pystina said.