ASTANA – Turash Abuov is one of Kazakhstan’s few composers who fought in World War II, using his music to capture both the darkness of war and the resilience of bravery. He continued to compose afterward, but his work has long been overlooked.

Abdulkhamit Raimbergenov. Photo credit: raimbergenov.kz

Today, his compositions are finally being reassessed and getting long overdue recognition, thanks to the new book written by Abdulkhamit Raimbergenov and Erbolat Alimkul. In the interview with The Astana Times, the authors shared the inspiration behind this extensive work.

Abdulkhamit Raimbergenov, dombra player and researcher, spent around a decade gathering and reconstructing Abuov’s biography—an exuberant, comprehensive work—after meeting him in 1983 during the expedition to collect kuis (traditional musical compositions) in the Zhambyl Region.

“In 1983, while on an expedition, I was searching for another kuishi-composer. One day, as I was sitting in a restaurant, a man named Turash approached me and invited me over, saying he had something artistic to share. We grabbed our tape recorder and went to his house—that was the first time I met him,” recalls Raimbergenov his first encounter with Abuov.

“Turash had an almost military-like presence, with a straight posture and a strong voice. He told me that his deepest emotions found expression through the kui and that he had been singing and playing the dombra since childhood. As he played, I noticed his distinctive style. He blended different kuis seamlessly, weaving together with songs and poetry, creating new forms of kui-song,” added Raimbergenov.

Erbolat Alimkul. Photo provided by author

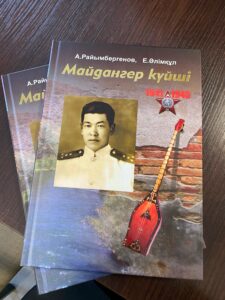

The result of that expedition is a book, “Maidanger Kuishi” (Front-line Musician), co-authored with Erbolat Alimkul, who have studied numerous regional archives to find the recordings and information on Abuov. Alimkul, a dombra player himself, was first drawn to studying Abuov because they shared the same hometown.

“I come from the same village in the Zhambyl region as Turash Abuov. While studying at the conservatory, I chose to focus on him for my thesis. We often listened to his ‘Arnau’ (Tribute) kui, but at the time, I had no idea he was from our own village,” said Alimkul.

“Arnau,” also known as “Kazakhstan Komsomol,” is one of Abuov’s most well-known kuis. Alimkul shared the story behind its creation.

“At the height of the [Second World] war, a group of young soldiers arrived from Kazakhstan. They were all sent straight to the front lines—and every one of them was killed. Turash Abuov was wounded as well and he lost consciousness. Just before blacking out, the last thing he saw was a tank bearing the name Kazakhstan Komsomol (Communist Youth League). That image stayed with him,” said Alimkul.

“When he came to himself in a hospital, the soldiers around him told him the heartbreaking news: none of the others had survived. The experience left a deep mark on him. Later, he composed a kui in their memory and named it Kazakhstan Komsomol, dedicating it to their sacrifice,” he added.

According to Alimkul, Abuov’s kuis do more than just reflect the experiences of war—they offer a deeply personal and vivid portrayal of the Kazakh soldiers who fought.

“Among the great Kazakh kuis, many were born during the Great Patriotic War. In this man’s work, the kuis dedicated to the war stand out as particularly remarkable,” said Alimkul.

“Turash Abuov was a man who fought on the front lines of World War II alongside many veterans of the Great Patriotic War, including Manshuk Mametova (machine gunner and Hero of the Soviet Union) and Ibraim Suleimenov (Kazakh sniper). This book preserves the memories of those individuals, along with the kuis dedicated to them and the handwritten notes left behind,” he added.

The book’s contents are pages of musical composition, memoirs, letters and handwritten notes.

“Maidanger Kuishi” (Front-line Musician). Photo provided by Erbolat Alimkul

“Additionally, this book includes the kuis composed for his closest friends, such as Azilkhan Nurshaykov (poet and front-line soldier), as well as those created after the war—telling the story of the war itself and the peaceful times upon return to the village once the war had ended,” said Alimkul.

Continuing his military career, Abuov spent many years living in Turkmenistan until he had to retire due to health reasons. His doctor gave him advice to return to his homeland even if it’s just for ten days.

“‘The soil of your birthplace will heal you,’ said the doctor. Abuov took these words to heart and he went back home. He lived there for another 25 years, and in gratitude for his return, he poured his emotions into music. That’s how Serpin kui was born,” said Raimbergenov, adding another story behind a famous kui.

Unlike traditionally structured kuis, Abuov’s compositions flowed with an unrestrained, almost improvisational quality, according to Alimkul.

“Turash Abuov’s kuis also contain the traditions of Karatau, Arka, and Zhetisu [regions]. His kuis were remarkably free—both in melody and structure. He wasn’t formally trained in a specific kui school; he was a self-taught musician, a naturally gifted kuishi. That’s why there were no boundaries in his performance—he played with complete freedom, creating truly unique works,” said Alimkul.