ASTANA – The conversation with architect and multi-disciplinary artist Asif Khan and his wife, Kazakh architect Zaure Aitayeva, took place under the white pavilions of the Islamic Arts Biennale in Jeddah earlier this year. The western terminal of Hajj airport, turned into a creative space for the biennale, offered a calm atmosphere to talk about life, art, and architecture. With sunlight casting soft patterns through the open-air structures, Khan spoke openly about his journey, the role of memory and feeling in his works, and shared commitment to shaping cultural spaces like the Tselinny Center in Almaty.

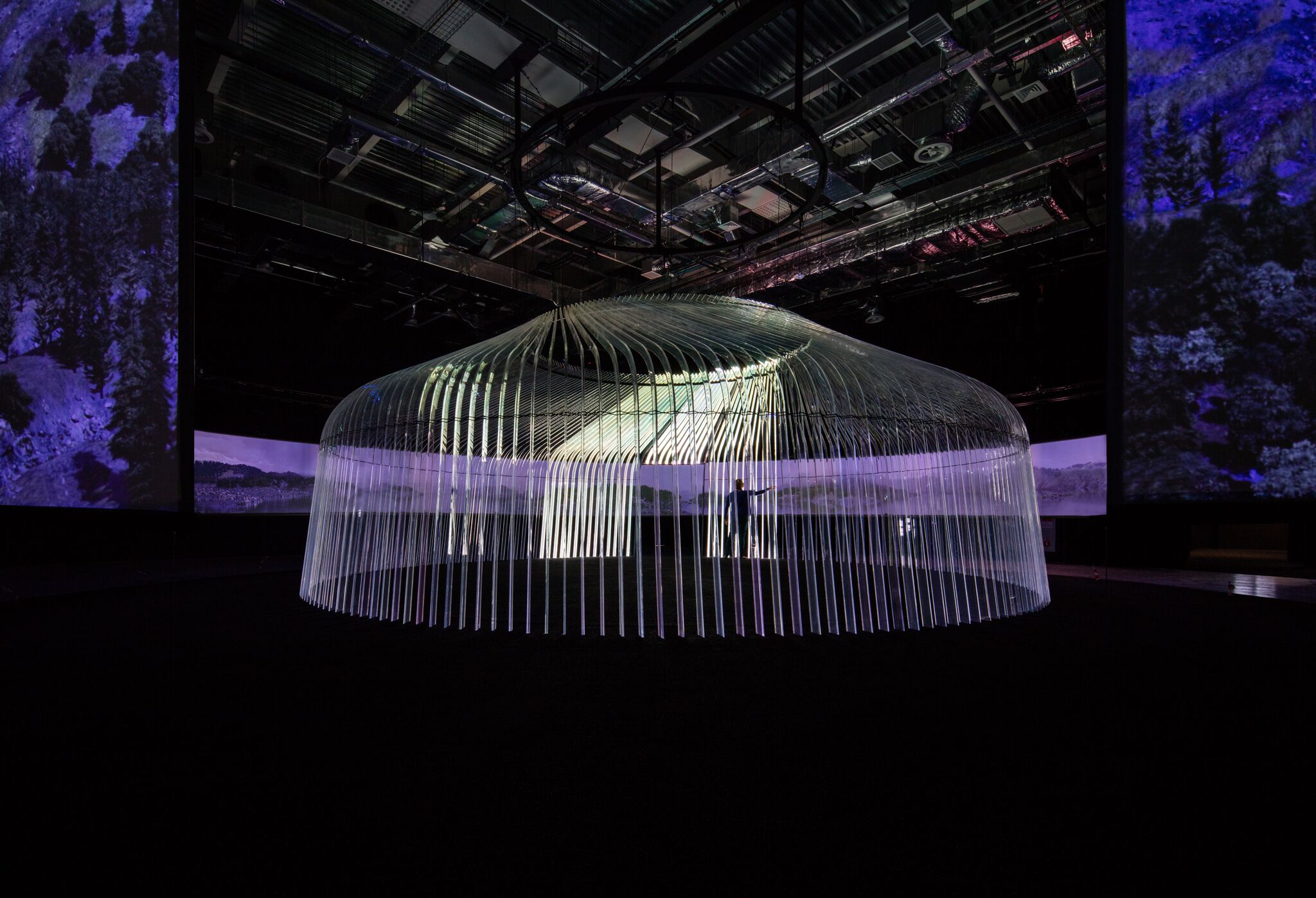

UK Pavilion at Expo 2017 in Astana. Photo credit: Luke Hayes

British architect Khan is widely known for creating the U.K. Pavilion at Expo 2017 in Astana, inspired by the theme of the Great Steppe and sound waves. Khan was awarded a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for Services to Architecture in 2017.

Below is the Q&A with Mr. Asif Khan.

Can you share your inspiration behind blending architecture with sensory experience and cultural exchange?

Asif Khan. Photo credit: Jérémie Souteyrat.

I spent much of my childhood deeply attuned to my surroundings. Growing up next to the Horniman Museum in London, I was constantly surrounded by the textures, sounds, and smells of diverse cultures and histories. It’s one of the early experiences which helped me become sensitive to how physical space interacts with sensory perception.

This sensitivity has stayed with me throughout my life and is central to my work today. Architecture, to me, can be a bridge between people and their environments. I am interested in what a space makes you feel and do. The texture of a wall, the echo of footsteps, the smell of the air, the light that filters through the windows. These sensory experiences are integral to cultural exchange because they communicate more than just information—they evoke emotion, memory, and connection. These memories are what makes each of us unique and inspire the creativity in us. I want to help people gain these kinds of experiences.

On beauty in design

“I believe that beauty, in its most fundamental form, is rooted in nature and in experiences that transcend the individual. In my designs, I seek to tap into those deep, primal feelings—like the sense of relief you feel when you finally reach a cool stream after a long walk on a hot day. The beauty of the sound of water flowing over stones, and the way the sunlight dances on its surface, connects to something innate in all of us. I believe this connection is universal, whether you are in a desert, a forest, or a city. Beauty, for me, is not just about aesthetics but a shared, almost spiritual, experience that brings us back to something timeless and elemental.”

What emerging trends or technologies in architecture excite you the most, and how do you incorporate them into your projects?

I’m not particularly concerned with trends, but I find it fascinating how technology can be used to deepen human experience. It’s important to remember that technology isn’t a new thing. The wheel, the yurt, the arch—all of these were once new technologies that transformed the way we live. In my practice, I aim to use contemporary technologies thoughtfully, to enhance the human experience without overwhelming it. It’s about creating solutions that work with nature and history, not against them. The real challenge is in finding a balance between innovation and tradition. I don’t think the future will have all the answers—sometimes the most profound solutions come from looking back, from learning how ancient civilisations like the Egyptians built structures that still awe us today.

Glass Qur’an. Photo by Marco Cappelletti / the Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

On creating the Glass Qur’an

“There is an idea described in the Qur’an that describes the nature of God as not only light (Nur) but as Nūr ʿalā nūr “Light upon Light.” I find this very powerful. Try to visualise what “light upon light” looks like in your mind. You might find yourself at the limit of your imagination, with this idea just beyond reach. I think that’s the wonder of the universe. It is really so far beyond human perception, that it makes us realise how small we are. Perhaps light, in its purest form, is both a physical and spiritual experience.

The Qur’an, as a spiritual text, has long been associated with light —whether in the light of understanding, or in the sense of divine illumination. With the Glass Qur’an, I wanted something that felt as though it were floating between the material world and the metaphysical. By making every page from extremely thin glass, light is able to travel through the entire Qur’an, illuminating every word simultaneously even when it is not opened. Some of that light reflects back to us, and some of the light reflects back to the universe. I think of it like the universe speaking to itself, or the creator speaking to us, its creation.”

What role did Arabic calligrapher Uthman Taha play in the artistic process, and how did his contributions enhance the essence of the piece?

The calligraphic work is fundamental to the work. It adds rhythm, clarity, and a deeper beauty. Because the appearance of work is made by the overlayering of 604 sheets of text, it requires absolute perfection of geometry and precision so that the viewer can have no distractions within the culmination of hundreds of thousands of letterforms.

Uthman Taha’s contribution was fundamental. His calligraphy is known as one of the most legible and perfect modern renditions of Qur’anic arabic. I wanted the words themselves to become a part of the physical space.

You’ve described the Glass Qur’an as transcending cultural and linguistic boundaries. What reactions have you observed from people encountering the work at the biennale?

It’s been moving to see how universally people have connected with the work. The Glass Qur’an seems to speak to people from different walks of life—Muslims and non-Muslims alike. It seems to transcend the divisions of culture and language, and it’s been heartening to hear people from all backgrounds describe how it resonates with them. I’ve seen people come back several times to experience the work again, often bringing friends or family along. That’s the kind of response I hoped for—a piece that feels personal and universally accessible at the same time.

The Tselinny Center is set to become Kazakhstan’s first independent cultural institution. What inspired you to take on this project, and how do you see it shaping the cultural landscape of Central Asia?

My personal story with the Tselinny Center began in 2017 at the World Exhibition in Astana where I presented the UK pavilion, and even before that, when I was doing my research about the Great Steppe culture as a part of the design process. The vastness of the landscapes, the philosophy of the nomadic civilisations to venture beyond the horizon, their motion in synchronization with natural cycles – this is what I found fascinating to explore in my work and to share with others through it.

That year I met my future wife Zaure who was the Chief Architect of Astana Expo. At the time she introduced me to Jama Nurkaliyeva who was running the Astana Contemporary Art Centre (ACAC) at Expo, and who was later appointed director of the new Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture in Almaty. It’s been a seven-year journey of shared visions about shifting perspectives on art, architecture, history and public discourse. I’ve always believed that artists play a central role in shaping the future of any society. Whether through visual arts, film, music, or dance, they are the ones who stretch the limits of what we can imagine, and in doing so, they stretch the limits of society itself.

Tselinny Center, Almaty. Photo credit: Asif Khan Studio.

Tselinny represents a new horizon for artists in Kazakhstan, a place where they can challenge the old ways of thinking and make new paths forward. My wife, a brilliant Kazakh architect, has been instrumental in this project from the beginning, believing in the importance of this new cultural place to elevate, to inspire, and to heal. Her belief that we can discover a new kind of architecture for Almaty, and for it to be a catalyst for artists and creative talents in the city to flourish, has kept me deeply committed to this cause. I often think of us as Tengri and Umai – the union of the creative forces of Sky and Earth in nomadic cosmology. As we found inspiration in the ancestral land and its layered history, there was also a dream about Tselinny being a boundless canvas inviting to add new stories, traditions and dreams.

The Tselinny Center, in my mind, will be a symbol of the region’s potential—a place where new ideas can be born, and where history can be reimagined.

How do you balance preserving the historical essence of the Tselinny Center with creating a contemporary and innovative cultural space?

The historical essence of the Tselinny Center is loaded with complex, colonial legacies, and it has been difficult to imagine how art could thrive in a place so burdened by its past. The building itself was so altered in the 1990s and 2000s, however, that it gave us a rare opportunity to see it with fresh eyes. It’s almost like reading a book whose last chapter is missing—where you’re left to imagine what it could be. This allowed us to bring a contemporary, open-ended vision to the space without the constraints of its original function. We’ve worked hard to respect its history while making it a place where art can move freely and boldly, unconstrained by its past.

On the legacy of Tselinny

“I hope that the legacy of Tselinny will show that it is possible to take old structures, which might be seen as obsolete, and re-imagine them as spaces for cultural growth and artistic exploration. It’s also about encouraging other cities and regions to invest in new spaces for art and culture, spaces that can create dialogue and exchange, rather than destruction. Tselinny isn’t built on a western template, it is really the beginning of its own template. An alternative future of Kazakhstan and Central Asia is in the hands and minds of artists, and I hope Tselinny can serve as an inspiration for how we can use our shared past to build something new.”

With a career spanning diverse geographies and mediums, how does working in Central Asia differ from your experiences in other regions like the UK or Saudi Arabia?

Each place I work has its own unique landscape, culture, and history, and I approach each project with the same openness and curiosity. But I think what makes Central Asia different is the profound sense of history here, the tension between the past and the future. The work is not just about design or architecture—it’s about uncovering the emotional and cultural landscape that exists in that place. In the UK, for example, I often feel the weight of history as a series of layers to peel back. In Central Asia, there is a different kind of rawness, an opportunity to search for and nourish identity. And this personal connection, this search for meaning, is what drives my work here.

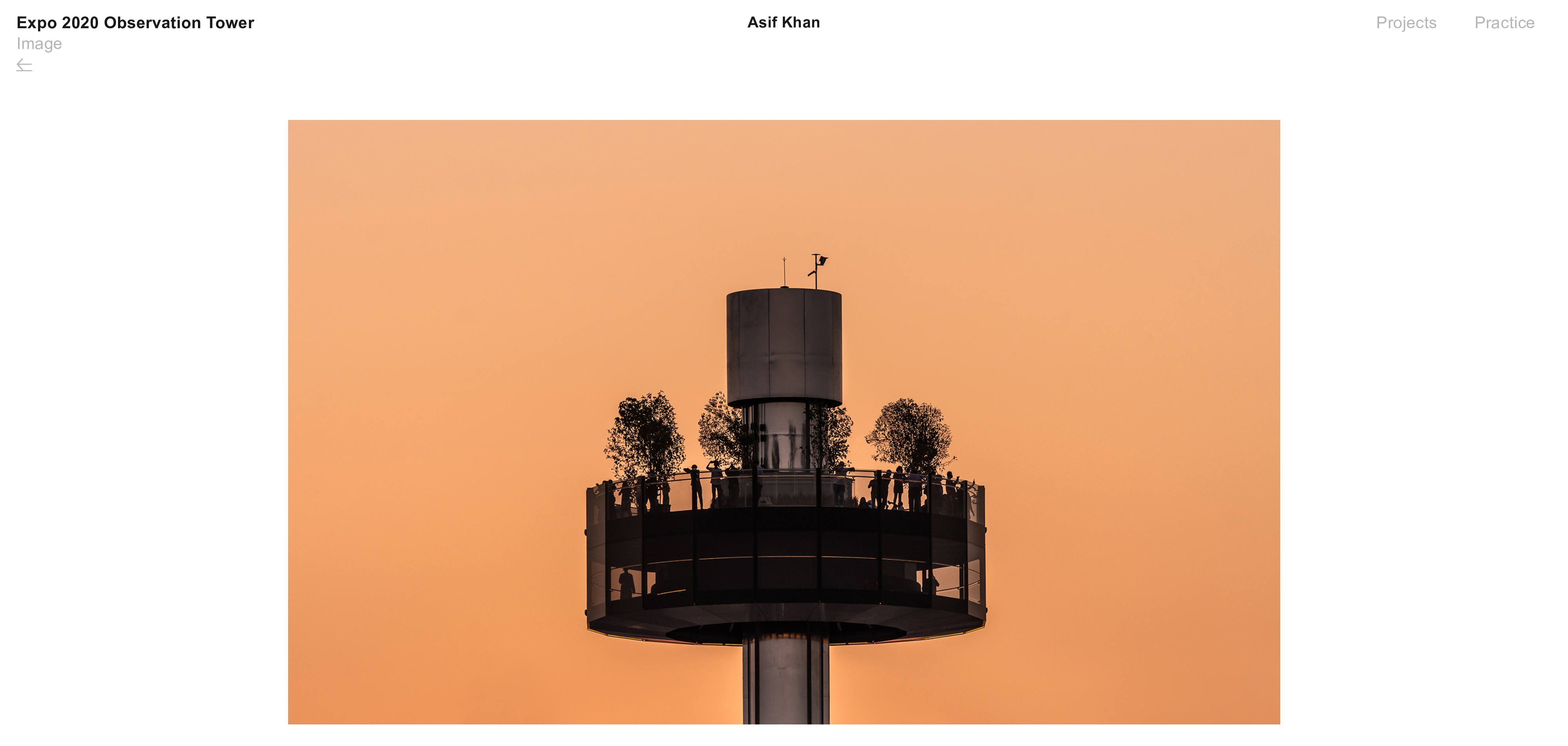

Expo 2020 Observation Tower. Photo credit: Asif Khan Studio.

What role do you think architecture and art play in connecting people to their spiritual and cultural heritage in the modern world?

Editor of The AT and author Zhanna Shayakhmetova during the opening ceremony of the Islamic Arts Bienniale in Jeddah on Jan.25, 2025.

Art and architecture are perhaps the most enduring means we have to connect with our deeper selves and our shared histories. In the chaos of modern life—wars, struggles, constant noise—art becomes a refuge, a way of grounding using something eternal. It allows us to connect with our past, to reflect on who we are, and to imagine who we can become. Art, at its core, is a form of spirituality, a way of reaching out into the unknown, and through that process, discovering a deeper truth about ourselves and our place in the world. This connection to culture and heritage is what will ultimately guide us through the turbulence of modern life.

***

Some accolades of Mr. Khan include the Coca-Cola Pavilion at the 2012 London Olympics, a transparent structure made from biodegradable materials. His studio also created the Hyundai Pavilion at the PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympics and the West Pavilion of the Dubai Expo 2020 entrance gates.

His works have been exhibited at the Serpentine Gallery, V&A Dundee, MAAT Lisbon, Vitra Design Museum, Royal Academy of Arts, Milan Salone, Milan Triennale, Federation Square Melbourne, London Design Week, Design Miami, Tokyo Design Week and Sharjah Architecture Triennale.

He was awarded the Architect of the Year 2018 by the German Design Council, and received the Grand Prix from Cannes Lions in 2014. He received the FX award for outstanding contribution to Architecture in 2024.