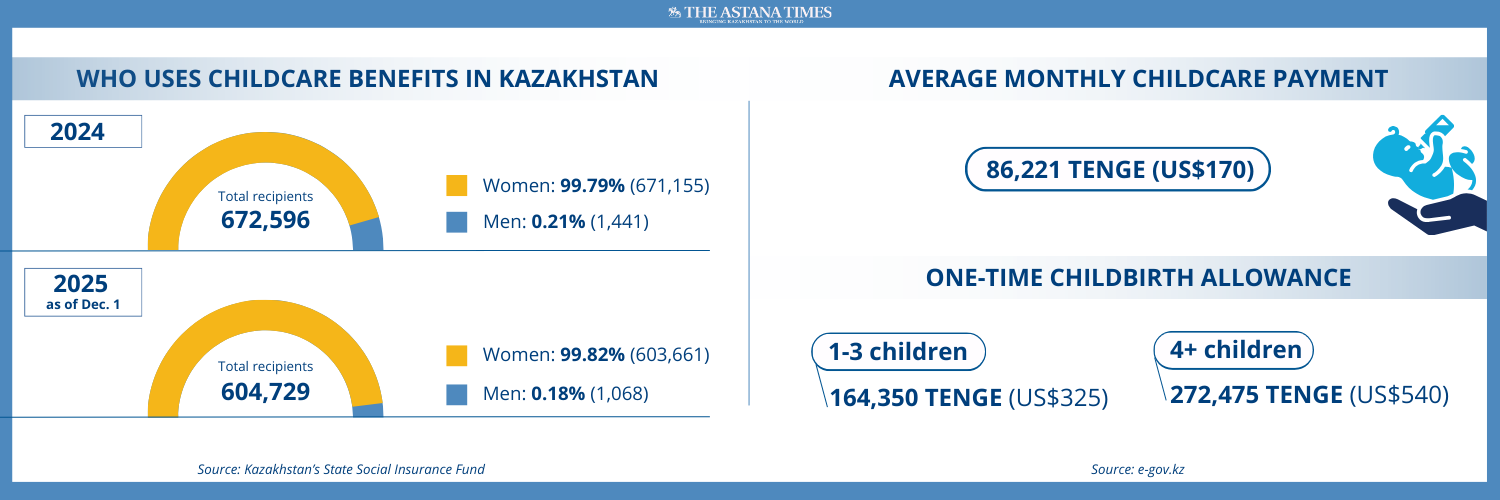

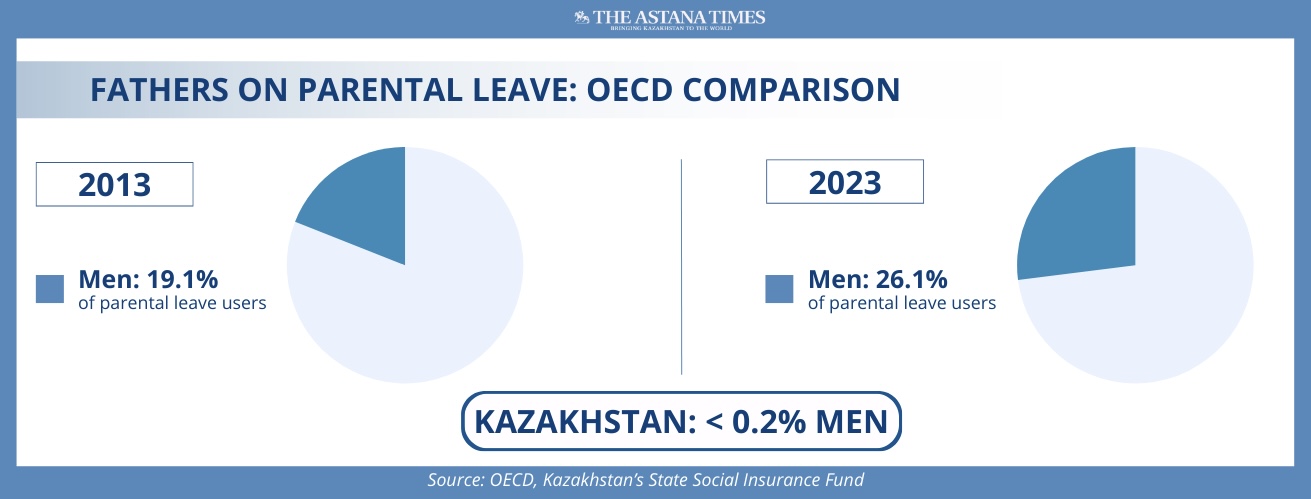

ASTANA — Kazakhstan’s social protection system formally promotes equal parental responsibility, including access to childcare leave and state benefits for both mothers and fathers. Despite laws allowing both parents to take childcare leave, women made up more than 99.8% of benefit recipients in 2024 and 2025, while men represented fewer than 0.2%, according to the State Social Insurance Fund.

Photo credit: Shutterstock

As of Dec. 1, 2025, 604,729 people in Kazakhstan received childcare-related social benefits, including 1,068 men and 603,661 women. In 2024, the total number of recipients was 672,596, with men accounting for 1,441 people, or 0.21%, and women for 99.79%.

Legal framework: maternity and childcare leave

Kazakhstan’s system distinguishes between maternity leave, unpaid childcare leave and social payments linked to income loss during childcare.

Under Article 99 of the Labor Code, women are entitled to 126 calendar days of maternity leave, or approximately 18 weeks. This includes 70 days before childbirth and 56 days after. In cases of complicated childbirth or multiple births, the postnatal period is extended. This leave is paid and counted toward work seniority.

At the same time, the Social Code regulates social payments linked to income loss during childcare. These payments remain available until the child reaches 18 months of age and are administered through the compulsory social insurance system.

After an 18-month maternity leave, either parent may request unpaid childcare leave until the child turns three. Article 100 of the Labor Code permits this leave to be taken by either mother or father. Employers must grant the leave upon a written application and submission of a birth certificate or an equivalent document.

How childcare payments are administered

According to Inna Stratulat, deputy chair of the board and chief of staff of the State Social Insurance Fund, the social childcare payment is assigned to an insured participant who provides care for a child until the child’s 18th month. The right to payments begins on the child’s date of birth.

“The amount of the childcare social payment is determined individually for each participant and depends on the recipient’s income over the 24 months preceding the month when the right to the payment arises, from which social contributions were paid to the fund,” Stratulat told The Astana Times.

The average actual monthly childcare payment for January-November 2025 was 86,221 tenge (US$170).

The fund does not collect statistics on how long parents take childcare leave by gender or how many return to work in the first year after childbirth. While receiving childcare payments, a recipient must inform the government within 10 working days of any changes to their eligibility, including a return to work. Once such a notice is submitted, payments stop from the first day of the following month.

State benefits at birth and during childcare

In addition to leave provisions, Kazakhstan provides several state benefits related to childbirth and childcare, funded either from the state budget or through the compulsory social insurance system.

All women who give birth, regardless of employment status, are entitled to a one-time state childbirth allowance paid from the national budget. In 2026, the allowance amounts to 38 monthly calculation indices (MCIs), or approximately 164,350 tenge (US$325), for the first, second, and third child.

For the fourth and subsequent children, the payment rises to 63 MCIs, or approximately 272,475 tenge (US$540). The MCIs for 2026 are set at 4,325 tenge (US$8.55).

Separate monthly childcare benefits are provided to parents who are not employed and are not participants in the compulsory social insurance system. These fixed monthly payments are also calculated using the MCIs. In 2026, they range from approximately 24,900 tenge (US$50) per month for the first child to 38,500 tenge (US$76) per month for the fourth and subsequent children, and are paid until the child reaches 18 months of age.

For working women, income support during maternity leave comes as a one-time social payment for income loss related to pregnancy and childbirth, financed by the State Social Insurance Fund. The payment is linked to prior earnings rather than a flat rate.

For example, a woman earning below minimum wage, which is set at 85,000 tenge (US$166) in 2026, could receive approximately 612,000 tenge (US$1,210) in net income during the standard 126-day maternity leave period. For higher earners, the payment is capped, with the maximum one-time benefit in 2026 reaching approximately 2.25 million tenge (US$4,440).

Employers can also increase maternity payments to full salary if stipulated in employment or collective agreements. The fund’s payment is then deducted from the total amount.

How Kazakhstan compares internationally

According to World Population Review, maternity leave duration varies widely across countries.

According to World Population Review, maternity leave duration varies widely across countries.

Bulgaria provides the longest minimum maternity leave at 58.4 weeks, followed by Norway at 49 weeks and Greece at 43 weeks. The United Kingdom offers 39 weeks, while Ireland and New Zealand provide 26 weeks.

Many countries allow parents to extend leave beyond the minimum period. In Estonia, mothers receive 20 weeks of fully paid maternity leave, followed by up to 62 weeks of optional parental leave. Austria offers 16 weeks at full pay and an additional 44 weeks paid at 73.1% of income.

Several countries require maternity leave to be paid at or near full salary. For example, Germany, France, Spain, and Austria, among others maintain full or near-full wage replacement during maternity leave. Norway replaces approximately 94% of income, while France and Bulgaria replace nearly 90%. These systems often combine maternity leave with broader parental leave options, allowing families to share care duties over a longer time.

Maternal and paternal leave: OECD patterns

According to a policy trends report published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in October 2025, most OECD countries provide paid leave for fathers through paternity or parental leave schemes. However, these benefits are usually shorter than those for mothers, and usage varies.

OECD data show that in 22 countries with available statistics, men accounted for 19.1% of parental leave recipients in 2013. By 2023, that share had increased to 26.1%. Luxembourg is the only country where men are more likely than women to take parental leave.

In Nordic countries such as Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Iceland, men account for a large share of recipients, although they still take fewer total leave days than women. In other OECD countries, including Australia and Poland, male participation remains limited.

“Fathers’ use of leave benefits not only parents and children but also promotes a more equal division of care responsibilities and other unpaid work at home and supports gender equality in the workplace, fairness and women’s economic self-efficacy,” reads the OECD report.

Public sector perspective

According to Assel Gutova, a graduate student at the Nazarbayev University Graduate School of Public Policy, the structure of childcare leave in Kazakhstan has broader implications for public sector staffing and career continuity.

“Every year, more than 235,000 women in Kazakhstan go on maternity leave. But returning to work after it is rarely accompanied by real support,” Gutova writes in her opinion piece for The Astana Times.

She noted that many countries have developed mechanisms to support women’s return to work after maternity leave.

In Norway and Sweden, parents often return through phased arrangements, starting with reduced working hours and gradually moving back to full-time schedules. In Germany, employers receive state compensation when women return to work after maternity leave, creating financial incentives to support reintegration. In France, a gradual return to work, combined with easy access to nurseries and kindergartens, helps many women return to work a few months after childbirth.

Gutova also noted the lack of systematic data on post-maternity employment in Kazakhstan.

“We know how many women take maternity leave, but we do not know how many lose their jobs or are forced to move to the private sector. (…) It is time to admit that supporting women after maternity leave is not charity or benefits. This is a matter of strategic sustainability of the public sector,” writes Gutova, highlighting flexible work arrangements, skills renewal programs, childcare infrastructure and systematic data collection as possible solutions.