ASTANA — When Dave Miley first set foot in Kazakhstan in 1993, tennis was still a niche sport confined mostly to Almaty. Fast-forward to 2020, when he returned as Executive Director at the Kazakhstan Tennis Federation (KTF), he found a country that had reinvented its approach to the game. In an interview with The Astana Times YouTube channel, Miley reflected on this dramatic transformation — from state-of-the-art facilities to a new generation of players making their mark internationally.

Miley said tennis is the best cardio. Photo credit: The Astana Times

“In my job with the International Tennis Federation (ITF), I visited many countries — from Estonia to Tajikistan — when they joined the ITF. Back then, everything in Kazakhstan’s tennis world was centered in Almaty. Astana wasn’t even the capital. The big difference now is what Bulat Utemuratov, the KTF President, and the government have done: they’ve built tennis centers across the country, brought in tournaments — it’s night and day compared to the past,” Miley told me as I tried my hand at serves on a court along Astana’s right bank.

For Miley, the accessibility of tennis to children across Kazakhstan is the game-changer. As he said, now, kids in Oral, Atyrau, Ekibastuz, Pavlodar, and Petropavl can all play tennis and compete in tournaments.

“It’s no longer just Almaty. Our under-14 boys’ national team currently competing in the Czech Republic includes two players from Aktobe and one from Almaty. The girls’ team features players from Aktobe, Almaty, and Aktau. That’s the big difference — tennis is really accessible now,” he said.

This, he explained, feeds directly into Kazakhstan’s long-term strategy. With experience across 140 countries for major organizations like the ITF, Miley says one principle stands out: to build a strong national program, you need both more players and better players.

“Every federation has two main objectives: more players and better players. You want to increase participation — that means 10-and-under programs, more coaches, more recreational players. And you also want to develop players who can compete in Davis Cup or at the top of the game. It’s not just about money, it’s about having a good system and using resources effectively,” he said.

He outlined the benchmarks for young athletes where a good under-12 player should play around 12 hours of tennis a week, five hours of fitness, and about 60 matches per year — against different opponents, on different surfaces.

I admitted to Miley that I came to the interview with doubts about Kazakhstan’s resources and whether the country could truly build a strong tennis team from scratch. He quickly dispelled them.

“Does Kazakhstan have the ability to develop good players? We’re already proving it. Right now, we have three boys in the world’s top 60 juniors — Amir Omarkhanov, Damir Zhalgasbai, Zangar Nurlanuly, and others — all from Kazakhstan,” he said proudly.

Another positive change he said that drives the progress is the rapid growth in infrastructure since 2020.

“The number of coaches has doubled from 200 to 400. We have many tournaments — not just professional ATP events, but junior competitions too. Players don’t need to go to Europe to develop anymore. Some eventually do for extra training and competition, but Kazakhstan can absolutely develop its own players. Look at Zarina Diyas — she grew up in Almaty, became world No. 40. That’s proof Kazakh players can reach the top,” he explained.

Miley shared with The Astana Times’ Aida Haidar that with tennis courts nationwide, the sport became more accessible. Photo credit: The Astana Times

Crucially, he added, success isn’t tied to wealth alone.

“It’s not just about money. Saudi Arabia is very rich but has no players. Meanwhile, countries like Argentina, which aren’t rich, always produce them. It’s about the system, not just the budget,” he said.

In fact, he emphasized that Kazakhstan now enjoys facilities that rival and sometimes surpass European standards.

“What amazes me is the infrastructure. We have excellent coaches, plenty of clubs, three gyms, indoor clay courts. Thanks to KTF President Utemuratov and the government, we have facilities you won’t find in many parts of Europe,” he said.

When asked about Elena Rybakina and Alexander Bublik, who raised Kazakhstan’s profile with major international victories, Miley acknowledged their significance but also offered perspective on the debate around “homegrown” versus “naturalized” athletes.

“Rybakina and Bublik have been very important for Kazakh tennis. What many don’t realize is that when the Soviet Union collapsed, ITF rules allowed players born in any former republic to represent another. Movement between countries wasn’t unusual. For example, Larissa Shevchenko grew up in Latvia but played for Russia,” he explained.

He shared that after Rybakina won Wimbledon, British journalists asked him about her.

“I said, look — she moved to Kazakhstan four years after Johanna Konta moved from Australia to Britain. Cameron Norrie moved from New Zealand to Britain. Greg Rusedski was born in Canada, but played for Britain. Garbiñe Muguruza was born in Venezuela, yet won Wimbledon for Spain. Many countries have benefited from player movement. And when our top players compete here in Davis Cup or Billie Jean King Cup, they always spend time with juniors, which inspires the next generation,” he said.

Returning to the game itself, Miley emphasized that the true essence of tennis lies in simply enjoying the sport.

“The heart of tennis is simple: rally and score. That was the idea behind the ‘Play and Stay’ campaign we launched in 2007 at the ITF. Once people rally, hit the ball back and forth, play points — they get hooked. That’s why we want every player, whether competing or watching, to ‘experience amazing.’ If they do, they’ll come back,” he said.

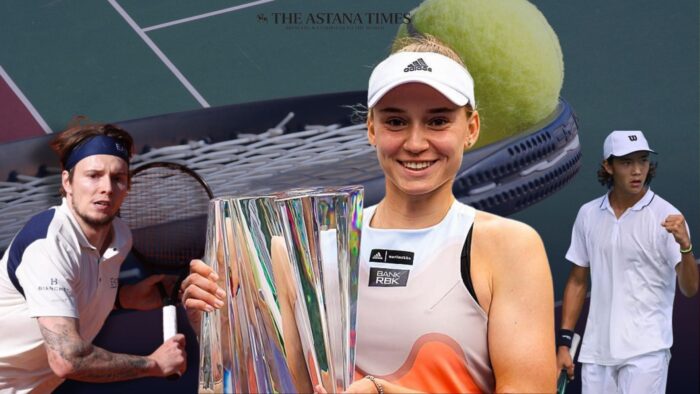

Rybakina, Bublik and many others raised Kazakhstan’s profile with major international victories. Photo credit: The Astana Times

This philosophy extends to coaching and player development.

“Every tennis center here now has a pathway. Just like in school — you start at five, you might finish with a degree, maybe a master’s or PhD, though not everyone does. In tennis, it’s the same: a child can begin with baby tennis, become a strong junior, maybe play professionally, Davis Cup, or Billie Jean King Cup. Not everyone will reach the top, but there’s a clear pathway, and parents can see it,” he concluded.

For full conversation, please watch the interview at The Astana Times Youtube channel.