Discreetly tucked away in a back street on the outskirts of Almaty, the former capital of Kazakhstan, lies a remarkable laboratory where wonderful objects, some of them dating back almost 3,000 years, are brought back to life. Ostrov Krym (‘The Island of Krym,’ as he likes to call it) is not just a treasure-trove of humanity, but also a testament to the remarkable skills of its founder, 72-year-old Krym Altynbekov.

Nick Fielding with Krym Altynbekov at his laboratory.

Personally supervising every stage in conservation and reconstruction, Krym is a spritely septuagenarian, his sparkling eyes incessantly darting from one beautiful object to another. Even his name somehow connects him to his profession. Altynbekov – ‘Honoured Golden Son’ – is particularly appropriate for a man who started life as a jeweller, before gradually moving on to the restoration of antiquities, including many from the period of the Scythians – or Saka, as they are usually referred to in Kazakhstan.

He made his name with his interpretation of the golden remains and grave goods of the Golden Man – Altyn Adam – a remarkable Saka chieftain, dating back to the 4th-3rd centuries BCE, which was found in 1969 in a kurgan (burial mound) just outside Almaty. Over 4,000 gold objects, as well as silver items, an iron sword and dagger, a mirror and wooden vessels were recovered from the kurgan, only part of which had been robbed in ancient times. Krym was too young to have been involved in the initial reconstruction of the costume, but not convinced by the way it was presented, he set to work himself to present it in a different way, one that was belatedly recognized as far superior by the archaeological authorities.

Nor is this his only work of importance. Krym has pieced together wooden chariots and horse tack including saddles and bridles, as well as the clothing and everyday objects of the nobles that have emerged in recent years from the countless kurgans that dot the landscape of Kazakhstan.

Even before getting into the lab, it is one of his twin daughters, Elina, who greets me at the door of the compound and quickly directs my attention towards a stele in the garden sitting on top of a large turtle. It’s a cast of one in Mongolia, where they are considered symbols of eternity. The great Mongol city of Karakorum originally had one at each corner, although now only two survive, their vast bulk and solidity making it difficult to destroy them.

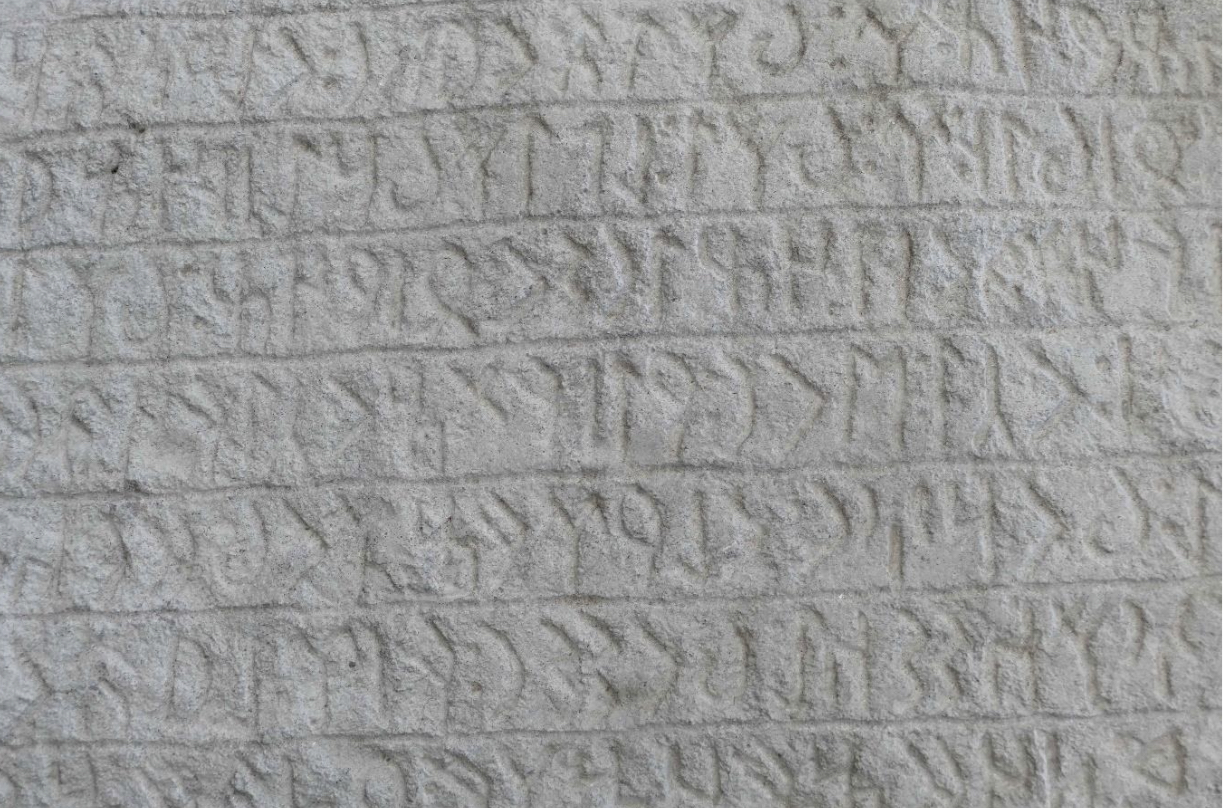

Stele with Turkic runes in Krym’s workshop.

The original of the stele in Krym’s garden, now broken into three parts, once sat in a recess on the turtle’s back. It is covered in Turkic runes, known as Orkhon Script after the valley in which they were first discovered by Russian traveler and Turcologist Nikolai Yadrintsev in 1889, and which was used by the early Turkic khanates from the 8th to the 10th centuries. Danish philologist Vilhelm Thomsen first deciphered the script in 1893 by betting that the word ‘Tengri’ – the all-powerful God of Heaven in the Turkic, Tuvan and Mongolian religious systems – would be likely to appear many times in such an extended piece of writing. He was right and from there he was able to unlock the script’s secrets.

Both the stele and the turtle on the ‘Island of Krym’ are exact fiberglass copies of the originals, “but even that had its advantages,” says Elina. “With angled lighting we found that some of the previously undecipherable letters could be read. For the first time it allowed us to make a complete transcription.”

Her father stands by, peering above his spectacles and waiting patiently to speak. We are taken into the first of several rooms, its walls lined with bookcases overflowing with tomes and dozens of objects, some old, other simple castings. A vast quantity of framed certificates record the patents Krym has taken out for the scientific techniques he has developed to preserve and reconstruct the many items that are brought to his door.

Headress of priestess found in Eastern Kazakhstan (reconstruction).

“Yes, I started as a jeweler, repairing damaged objects that were brought to me. Gradually people began to trust me with more and more items, many of them very ancient, but often in poor condition. As word got around, I found it was increasingly museums that were coming to my door. The items in their collections were either fragile when first discovered or they had deteriorated after not being looked after. That is how it all started.”

In a corner of the second room, in front of the groaning shelves, stands a mannequin dressed in red robes and wearing an ornate golden crown over a red headdress. It is a reconstruction of the body and burial clothes of a 4th-3rd century BCE Saka woman, more than likely a priestess. She was found close to Uzhar, at the foot of theTarbagatai Mountains in Eastern Kazakhstan. Elina explains: “The grave was unmarked, probably because she was a very powerful woman, something like a priestess, and those who buried her wanted her to remainhidden.”

In one hand she held what appear to be fern leaves – a typical motif for such a person, as they signify knowledge of medicine. (Later we see little gold bands from another burial in which cast fern leaves are clearly visible.) On the other hand she held a small bowl full of seeds. “We found seeds from 12 or 13 different medicinal plants,when we examined them under the microscope,” Elina adds.

A close-up of the headband.

The remarkable crown is made from gold, fashioned into the shape of a bird – possibly a pheasant, says Elina,but just as likely a representation of some mythical creature such as a phoenix or simurgh. Krym walks over to highlight the golden symbols in a band across her brow. But as Elina points out, it is not really the goldwork that is important about this reconstruction: “Gold can only tell us so much,” she says. “Organic matter holds so much more information. In this case, we were able to work out from just a few surviving strands that her dress was made from wool dyed with madder to make it red. And her headdress was made of silk that came from China.”

This is fascinating. It is accepted by archaeologists and historians that sheep wool did not reach China until the 2nd century BCE, several centuries after the woman priestess was buried.

Recovering this body was no easy task. She had been buried in a pit in the ground, its four sides marked by large stones, with another three large flat stones laid on top. The gaps in between the stones had been filled with clay to stop the air getting in. Even so, the extraction of this important find presented difficulties. Krym developed a unique technique for stabilizing the remains in situ and lifting out the entire surface area of the grave without disturbing the skeleton and artifacts. This involved supporting it from beneath and packing it from above with thin polyethylene bags filled with dry, finely sifted sand, compressed to remove the air. This method is called kumdorba (“sandbag” in Kazakh).

Next, a protective structure made of 30–40 millimeters thick boards was formed by inserting transverse boards. A “tunnel” was then punched into the ground below the floor level (or bottom of the grave),into which a single board was inserted and pressed tightly against the lower surface of the extracted massif; the free space is again tightly filled with soil. The process was then repeated, thus ensuring that the block being cut out always rested on the ground, and the skeleton and artifacts remained safe. The boards were fastened together with screws or tied with ropes and the shield was reinforced with longitudinal boards. It could then be lifted safely.

Elina shows me pictures of another remarkable reconstruction of a Saka warrior’s coat that had originally been studded with hundreds of tiny golden tigers. The original find was at a kurgan at Baiga-tobe in Eastern Kazakhstan.

Original grave showing golden objects similar to those from Baiga-tobe. Arzhan-2, Tuva.

On the back of the tigers there were two loops for sewing on clothes. However, due to the fact that the mound was plundered, it was difficult to determine exactly where the tigers and other decorations were located, and precisely how many there were. Usually, in such cases, scientists rely on data from similar unplundered kurgans.

One of the tiny golden tigers sewn onto the coat.

In this case it was the famous Arzhan-2 kurgan in Tuva. The excavations of Arzhan-2 were completed in 2003. The Joint Russian-German expedition, directed by Konstantin Chugunov and Anatoli Nagler, found a rich burial of two people – a man and a woman – with very similar decorations for clothes. The decorations from Arzhan-2 were also made of gold and in the form of tigers, also had two loops on the back. The researchers of Arzhan-2 had already made their own reconstruction.

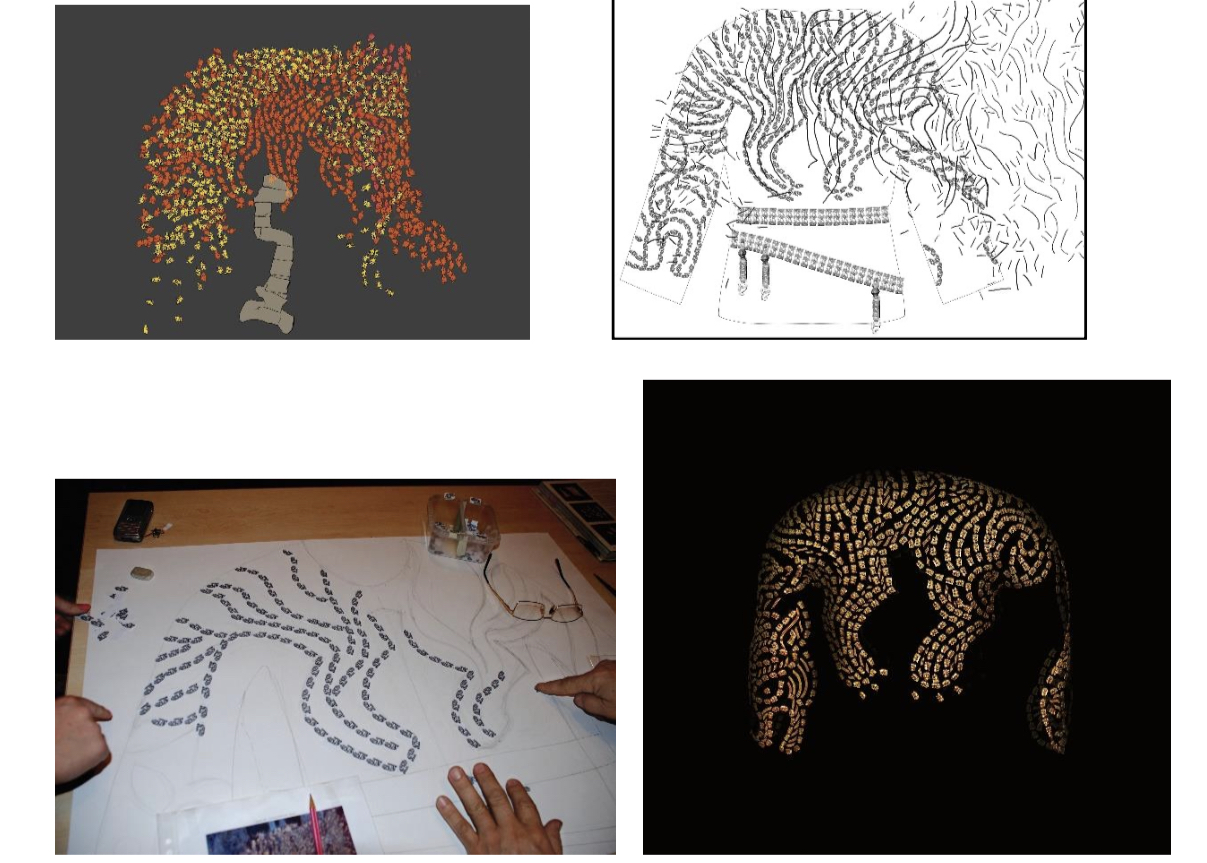

How the pattern was reconstructed to create the design of a tiger.

Much of the initial analysis of the remains took place in St Petersburg. But with little remaining of the woolen coat to which the golden tigers had been attached, the archaeologists had been faced with a pile of the tiny metal beasts in what seemed to be a jumbled heap.

Final version of the jacket with tiger medallions attached.

It was initially thought that the ornamentation in Arzhan-2 was some kind of flame-shaped design. But Krym was not convinced by the reconstruction, having noticed that some of the little tigers were facing up and others down. By using photographic scanning techniques, he and his team worked out the near-exact position of each of the tigers on the garment. Those facing down must have come from the back, he surmised, and those facing up were from the front.

Soon they realized that all the little tigers were themselves in the shape of a single tiger, as if it was draped over the shoulders of whoever was wearing the coat. Other embellishments looked as if they were the tiger’s stripes. When originally worn the coat must have been a remarkable and impressive garment as its golden tigers sparkled in the sunlight. The reconstructed coat is now in the National Museum in Astana.

We continue our journey through Krym’s lab and find out that it is not just the ancient Saka artifacts that he restores. In the third room are two of the doors from the inner sanctum of the Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yassawi – a renowned Turkic poet and Sufi mystic – in Turkestan, southern Kazakhstan. This great building was originally commissioned by Timur in 1389 and although unfinished, it remains one of the best preserved Timurid Buildings in Central Asia. The wooden doors, inlaid and carved by Persian craftsmen with intricate patterns at three different depths, are more than 600 years old.

At first, there was skepticism that the doors needed much work. “They told us they were fine and would last for many more years,” says Krym. “But X-Ray analysis showed huge hollow spaces inside where termites had been busy.” To repair the damage Krym soaks the wood in a patented solution of alcohol and polyethylene glycol to strengthen its structure. Using a hypodermic syringe, he injects the solution into existing cracks in the wood so that no further damage is caused to the doors. Pareloid is used to fill the holes and thus strengthen the wood. Already the work has taken six years and is not yet complete. When finished the doors will go to a museum close to the mausoleum, rather than into the building itself. An exact replica will then be fitted back into the mausoleum.

One room follows another. In the next one we find a life-size model of a horse dressed in all the finery of Saka decoration, with huge ibex horns attached to the horse’s head. The wooden bridle is covered in gold leaf and rams’ horn motifs decorate the red woolen bands that hold the elaborate headdress in place. There are no stirrups, but a crupper neatly holds the decorated saddle in place.

Elsewhere we are shown swords and spears, some made of iron. The wooden shaft of the spears and scabbards of the swords can clearly be seen, providing organic evidence of age and the species of tree wood that was used. Krym specializes in reassembling objects from organic material, and we see an almost perfect wooden pillow that was little more than a pile of flakey brown material when it was first discovered.

With a lifetime of work behind him and the respect of archaeologists around the world Krym has ensured the continuity of his projects; his wife Saida and both his daughters, Elina and Dana, work with him and a team of a dozen or more skilled craftsmen. He remains independent on his little ‘Island of Krym’ and as eager as ever to continue his work. How does he feel when he wakes up every morning, I ask him. “I’m up at five and in the lab by six,” he says without hesitation. “This is what I love to do.”

The author is a British author and journalist.