ASTANA – An interplay of musical performance and a tiny bit of puppetry magic is unveiled in the ancient Kazakh traditional orteke art form, which last month was included in the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

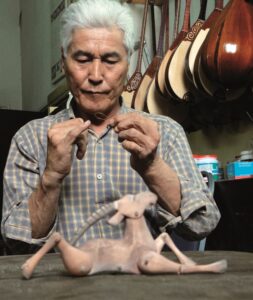

The secret to a masterful orteke performance also lies in the skill of the master woodcarver. Photo credit: Studio Mergen, ich.unesco.org.

In the hands of a skillful dombra (Kazakh traditional instrument) player, the inanimate objects on the surface of a drum begin to take on a mysterious dance of their own. From afar, the performer might look like a magician or a snake charmer playing the flute to a wriggling snake.

Yet there is no magic. The principle of orteke is very simple: the player controls the puppet (usually a wooden goat) through a string tied to his or her finger that plays an instrument, most commonly a dombra. While playing the musical instrument, the puppet performs rhythmic movements intact with the melody.

Some say the Kazakh puppet theater originated with orteke, but certain differences prevail. In classical puppet theaters, the puppet actor leads the puppets directly himself or herself, in orteke puppetry, the musician conducts the figure or several figures indirectly through the instrument.

In 1935, Akhmet Zhubanov, a well-known researcher and scientist in the field of music, published an article in the Kazakhstanskaya Pravda newspaper, describing the orteke art form.

“During the play, the figures jump, bend, and make various twists and turns. Sometimes, the figures of horses, men and women are used by the player as well. They dance to the rhythm of the music. The skillful performer created a mood and brought the above-mentioned figures to different shapes, sometimes jumping up and sometimes running,” he wrote.

Zhubanov mentioned such an exquisite and unusual art form is nothing without an equally talented dombra player. In the past, musicians could play up to five-eight figures of goats simultaneously, which was considered a sign of a masterful performance.

Orteke puppetry, however, has become far less visible today, as only few people can engage more than one figure in a performance. The fact that UNESCO has added the genre to its collection of intangible cultural heritage shows that the art form is deemed worthy of protection and promotion in the future.

Symbolism in orteke

Orteke has absorbed the musical, playful, but at the same time sacred components of the traditions of the nomadic people. According to Yerkin Zhuasbekov, a renowned Kazakh theater playwright and an art history scientist, orteke has brought a wide variety of theatrical styles and unique “steppe theater” to Kazakh folklore.

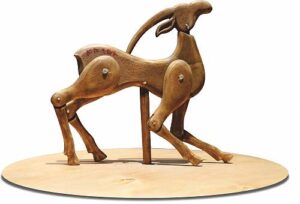

Orteke might serve as a window into the once flourishing Kazakh hunter experience, symbolizing the movements of a trapped mountain goat. Photo credit: Studio Mergen, ich.unesco.org.

The word orteke derives from two components: “or” is, in this case, a prefix, which means a pit, ditch, ravine, trap, and grave, and “teke” means a mountain goat.

Here one can see a clear resemblance to hunting experiences, where an animal trapped in a pit, usually a mountain goat-teke trying to free itself, would jump, twirl and perform other abrupt movements, which probably formed the basis of orteke.

Orteke thus might serve as a window into the once flourishing Kazakh hunter experience.

Despite the wealth of detail behind the performance, the experience is quite calming and meditative, with steady rhythms that are also rooted in the ancient shamanism practices in the culture of the nomads.

Besides preserving the Kazakh hunting phenomenon, orteke also strives to represent ancient symbols in images of animals, particularly the mountain goat.

The tradition of depicting zoomorphic images in Kazakhstan has an ancient history beginning with petroglyphs of the early era and ending with the traditional Kazakh ornamentation where the ornaments of goat horns prevail.

From ancient times, the mountain goat symbolized man’s power, and its horns were understood as an accessory of the chief or strongest warriors.

On the other hand, the goat was also symbolized as a carrier of divine chaos. In orteke, a man can control it, delivering a message that a man can control the goat’s “wild” nature if necessary.

A puppet could be a far more compelling story narrator than an actor. Strings pulled by a trained musician and backed by dance make the inanimate doll relay a message like no live actor can. The goat is an important and popular character in Kazakh fairy tales and is often portrayed as intelligent and witty: it often helps and guides the slow-witted rams.

The orteke dance adds a unique flavor to the experience of a story-telling genre.

An art form that requires mastery of all

The celebration of culture is not only present in the music or puppetry of orteke, but also other vibrant elements of the production — from the making of a doll to the choice of materials and the table.

Orteke parts are carved out of wood and require craftsmanship mastery. Photo credit: Studio Mergen, ich.unesco.org.

The secret to a masterful performance also lies in the skill of the master woodcarver. The Orteke doll’s joints must be mobile so that the figure can jump and gallop like a real mountain goat. This is achieved through the special engineering of the orteke’s joints, which are divided according to the animal’s anatomy into at least three parts.

In the past, the moving parts were connected by gut strings. Modern craftspeople prefer to fasten them with wooden rivets. The legs of the figure are attached to the body loosely, dangling. Only the body of the animal is solid in the doll. The head of the goat with horns is carved together. The neck section is sawn out separately and attached to the body with rivets. The whole figure is then mounted on a steel pin.

The flat surface of the field on which the orteke dances is usually a circular or quadrangular leather membrane made of fine goatskin. In addition to their knowledge of leather dressing and drying, nomadic Kazakhs were well-versed in the acoustic properties of leather.

Due to its material properties of thinness, durability, and soundness, goatskin is still widely used in many cultural traditions worldwide in making musical instruments, particularly drums. Goatskin enabled musicians to make their instruments sound resonant, bright, and clear, while the thinness and durability of such leather allowed a wide sound range to be produced.