ASTANA – Kazakh traditional ornaments are a vital part of culture, commonly seen in clothing, jewelry, and household items including rugs, blankets, and pottery. The intricate designs, featuring geometric patterns, floral motifs, and animal depictions, serve as decorations and amulets.

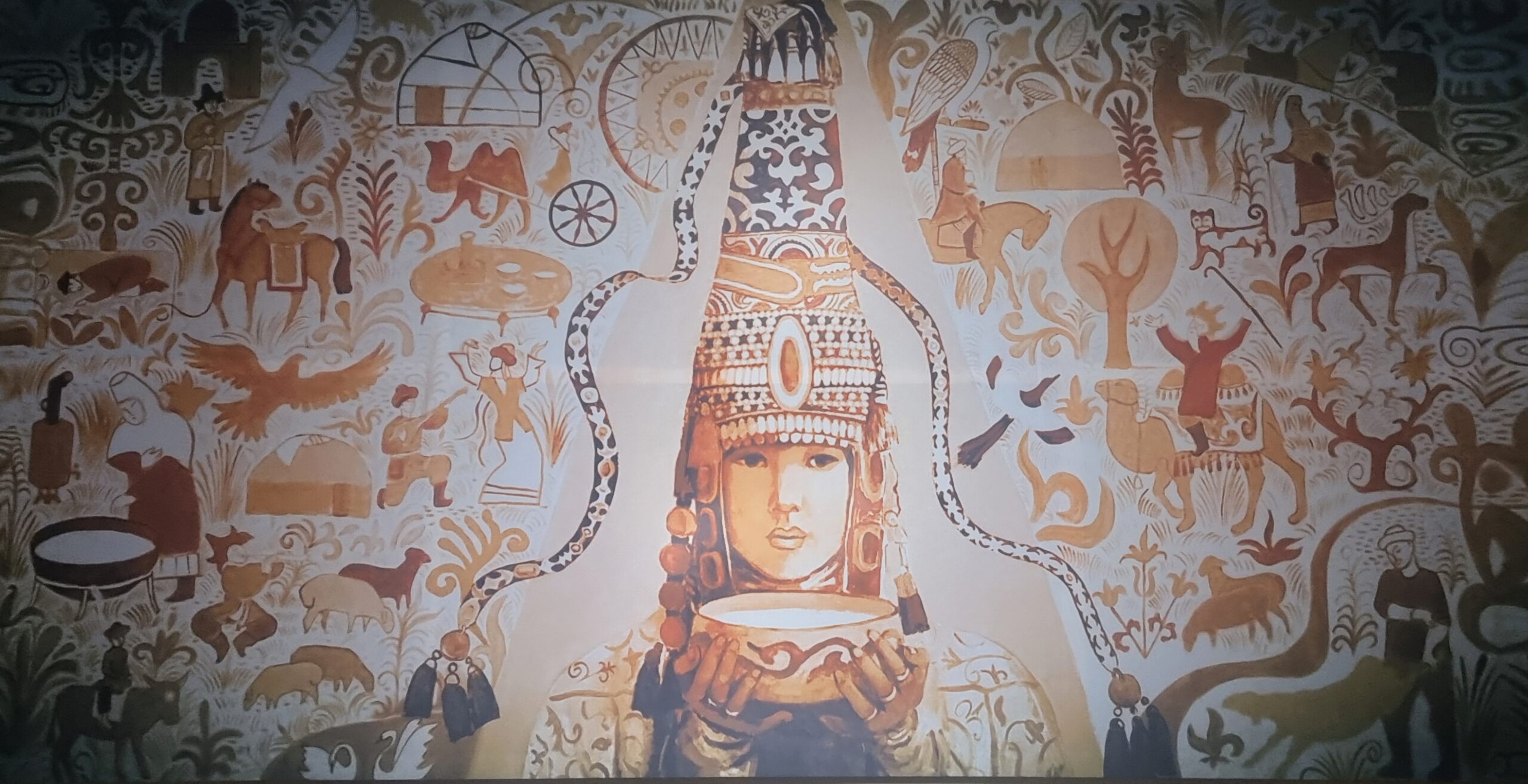

Picture at the National Museum in Astana. Photo credit: The Astana Times/Aiman Nakispekova

In an interview with The Astana Times, Aizhan Kurbanova, a junior researcher at the Central State Museum in Almaty, explained the cultural significance of these ornaments, emphasizing their role in preserving cultural heritage and showcasing artisans’ craftsmanship and creativity.

“For the Kazakhs, ornament became the main form of fine art, capturing the essence of their people and their deep connection to nature. A few centuries ago, nature was revered as a nurturing force that provided sustenance, clothing, and healing,” she said.

More than decoration

Aizhan Kurbanova, a junior researcher at the Central State Museum in Almaty. Photo credit: Kurbanova’s personal archieve

According to Kurbanova, since ancient times, people have depicted signs of heavenly bodies, warming fire, water, green shoots, ripe ears of corn, and fat herds on household utensils and home decorations as symbols of children’s health and the earth’s fertility.

Kazakh ornaments date back to the Neolithic era, with early examples found in the Andronovo culture of the 16th-17th centuries BC. These designs often included geometric shapes, animals, and natural patterns, serving as artistic texts that conveyed ancient people’s understanding of the world.

“The nomads perceived the world through the sun, represented as a circle. That is why the shanyrak (the upper part of a yurt) is in the form of the sun, a symbol of Tengri. At the same time, people knew the yurt should be placed with the door facing east so the sun’s rays could penetrate inside. The shanyrak served as a compass: the rays fell on the yurt’s skeleton, determining the time of day,” said Kurbanova.

Elements of Kazakh ornaments could indicate belonging to a clan or a zhuz (alliance of Kazakh nomadic tribes), and their symbolism often conveyed a message.

Baskurt is a patterned woven braid used for decorating a yurt. Photo credit: Kurbanova’s personal archieve

“According to ancient Turkic beliefs, the bird symbolizes heaven, the fish symbolizes water, and the wood symbolizes earth. The masters tried to accurately convey images taken from nature in their masterpieces. The products depict animal body parts, horns, hooves, and plants,” said Kurbanova.

Symbolism and color in traditional ornaments

Kurbanova noted that scientists have identified about 230 types of Kazakh ornaments, divided into four main categories: floral, zoomorphic (animal), geometric, and cosmogonic (astrological).

Korzhyn, a bag is made of felt using a mixed technique, featuring zoomorphic, floral, and geometric patterns. Photo credit: Kurbanova’s personal archieve

“The “muyiz” (horn) is considered the primary element, serving as the basis for other ornament types. Only the names have changed, such as “koshkhar-muyiz” (ram’s horns), “argaly-muyiz” (argali horns), “bugy-muyiz” (deer horns), and “kyryk muyiz” (forty horns),” she said.

Floral ornaments feature various plant forms, such as leaves and flowers, both individually and in combinations called “zhapyrak” (leaf) and “ush-zhapyrak” (three leaves). One notable example is the “ayshyk gul” (moon flower).

“Geometric ornaments include shapes like rhombuses, squares, and triangles, frequently used in woodwork. These patterns often consist of broken lines ending in oval curves, known as “irek” or “ireksu” (winding, zigzag). Cosmogonic ornaments, or those related to astrology, feature elements like “dongelek” (circle), “shugyla” (sun ray), “bitpes” (infinity), “ai” (moon), “kun” (sun), “zhuldyz” (star), “shimai” (spiral), and “tortkulak” (crosspiece),” said Kurbanova.

Like many ancient cultures, the nomads viewed images of revered animals as talismans. Instead of depicting the entire animal, they often represented only parts of its body, such as horns, which were believed to hold special power.

Kurbanova noted that horn-shaped ornaments in Kazakh folk art commonly symbolize vitality, grace, prosperity, and well-being.

“The presence of arched and spiral-shaped horns in animals was viewed as a divine mark and a symbol of their peaceful role in serving humanity. Additionally, well-known zoomorphic motifs such as “kargatuyak” (crow’s foot), “ashatuyak” (cloven hooves), “kusmuryn” (bird’s beak), and “kus kanat” (bird’s wing) have deep roots in ancient Saks art, reflecting vivid depictions of animal life,” she said.

Kurbanova said that when wishing someone happiness, people would give gifts adorned with symbols like “kusmuryn” or “kuskanat”. If a married woman sent her parents a gift decorated with a bird’s beak pattern, it indicated her contentment in her new home.

Kise is a waist bag for hunters, adorned with cosmogonic and geometric ornaments. Photo credit: Kurbanova’s personal archieve

In ancient times, the choice of colors in ornaments carried symbolic meanings and expressed various concepts and ideas.

Kurbanova explained that the three primary spectral colors—blue, yellow, and red—and the two achromatic colors—white and black—each symbolized different desires and feelings.

“Blue represented the sky and reverence for Tengri, red symbolized fire and the sun, while white stood for purity, joy, and happiness. The yellow color indicated intelligence, black represented earth and green signified spring and youth,” she said.

Dyes were made from natural sources such as cattle blood, black liver, and various fruits and plants, including cherry, hawthorn, currant, blackberry, and rosehip. Craftsmen often used methods of cooking and staining processes to achieve the desired hues.

Ornaments as essential cultural artifacts

Kurbanova emphasized the importance of preserving and sharing knowledge about traditional ornaments, noting their omnipresence and their role as a cultural record for future generations.

Onirzhiek – silver made chest jewellry. Photo credit: Kurbanova’s personal archieve

“Traditional ornaments reflect the intellectual and aesthetic worldviews of our people, capturing the essence of natural phenomena. Historically, these decorations served as both art and functional symbols,” she said.

Kurbanova also highlighted that one of today’s key challenges is reviving cultural and historical heritage, including spiritual traditions and customs.

“While ornaments once held significant ritual and functional roles in daily life, their meaning has diminished over time. However, modern folk artists are infusing new content and transforming these traditions into contemporary forms,” she said.

“Ornaments serve as a cultural chronicle for the Kazakh people, much like oral folk art. They deserve recognition alongside other art forms, including applied, fine art, and architecture. Regardless of the beauty of the craftsmanship, no creation is complete without ornaments and patterns,” added Kurbanova.