How can Kazakhstan’s leader gain respect on both sides of this world’s many barricades? A good question to answer on the Day of the First President.

On the Day of Kazakhstan’s First President political analysts, historians and just people with long memories, who remember what Kazakhstan has been through in the last 50 years – they all ponder on the phenomenon of Nursultan Nazarbayev. How has this man been able to gain the respect of everyone, including bitter opponents, standing on opposing sides of the modern world’s many barricades? If someone thinks this is an exaggeration, just look at the facts.

Nazarbayev is praised and valued by the supporters of the Soviet Union and its passionate critics, by Russians and Kazakhs, by Asian and Western presidents, by communists and anticommunists.. What is his secret?

Dmitry Babich

There is no question about the respect and love for Nursultan Nazarbayev from his own people, Kazakhs and non-Kazakhs living in Kazakhstan. A bright boy born in a simple farmer family at the piedmont of Alatau mountains, he grew from a simple metal worker to the position of the first president of independent Kazakhstan. He gave Kazakhs not just their first independent state (which was an achievement in itself), he made that state a modern, fast-developing country.

But Nazarbayev is also praised and respected by people around the former Soviet Union. They remember and value his quality which in the Soviet times was called “internationalism” and which comprises a variety of positive meanings in modern English language. It is not just tolerance, it is something more. Since his childhood, Nazarbayev lived inside the amalgam of representatives of all ethnic groups inhabiting the Soviet Union (and it was one-sixth of the world’s landmass).

“Boys playing in the street in his native Chemolgan town could be named Richard (Kazakhstan became a new home for hundreds of thousands of Volga Germans exiled by Stalin), Bohdan (a typical Ukrainian name) or Oleg (a Russian). They could be living in the next building of the block, and they made friendships based on merit and soul, not on the native language,” writes Olga Vidova, an author of Nazarbayev’s biography.

Having worked for five years in the “hellish heat” of metallurgical plants of Ukraine and Kazakhstan’s Temirtau, Nazarbayev knew the needs and wishes of working people. He made every effort to preserve the ties between Soviet republics inside the collapsing Soviet Union in 1991, and later he made Russians feel at home inside independent Kazakhstan.

Nazarbayev’s fans in Russia even say the USSR would not have collapsed if Nazarbayev had become the Soviet Union’s prime minister – and he was groomed for this position in 1990-1991. A prominent Russian political scientist Yuri Solozobov was speaking for millions of people in Russia, when he wrote in the year 2000 that Russia could have been much happier under Nazarbayev than under Boris Yeltsin in the 1990s. And Russia’s current president Vladimir Putin was speaking for the whole nation when he called Nazarbayev, and not himself, the author of the project of Eurasian Economic Union and a “tireless promoter” of the idea of Eurasian integration.

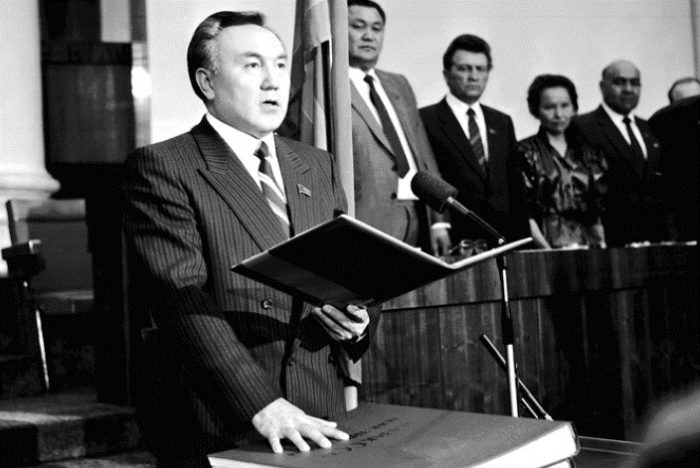

The Supreme Council of the Kazakh SSR adopts a law on renaming the Kazakh SSR into the Republic of Kazakhstan and conducts the inauguration of the President of Kazakhstan on Dec. 10, 1991. Photo credit: Elbasy.kz.

Western leaders and the presidents of Russia and Turkey also give his due to Nazarbayev – if only because Kazakhstan is (correct me, if I am wrong) the only country in the post-Soviet space which managed in the 30 tumultuous years of independence to preserve good relations with both Russia and the West, carefully avoiding confrontation with anyone.

Is there any other leader in the world who could boast of being praised by such different political leaders as president Sarcozy of France and president Recep Tajip Erdogan of Turkey, president Trump of the United States and the former German chancellor Gerhard Schroder?

So, what is the secret of Nursultan Nazarbayev, why is he praised by almost everyone? Let it be my guess, but I stand by it: because he never lets himself be lulled by the praise. For all of his life, Nazarbayev chose the hard ways over easy ones, and warned of dangers looming ahead at the seemingly peaceful moments of general relaxation. This is the secret of his popularity and his longevity in power.

Kazakhstan’s First President Nursultan Nazarbayev delivers historic first speech at the 47th session of the UN General Assembly in New York on Oct.5 in 1992 when he initiated the establishment of the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia. A screenshot from the archive video.

Nazarbayev loved and cherished his native Alatau mountains, he was the elder boy (and, of course, the leader) in his family of four children. But he knew his time had come to leave when he graduated from high school. “I will never forget how my father sold the only little bull that he had. He raised and nourished that animal by his own hands,” Nazarbayev wrote later in his memoirs. “But he sold the bull and all the money that he got for it – 2,800 rubles, I remember – he gave that money to me, so that I could try to pass the entrance exams for Almaty State University.”

The 18 years old Nazarbayev did not pass the exam, entrance rates were pretty low for the “provincial” boys of his type, but he turned this big minus into a big plus. First, he saw how corrupt the system could be. Second, he became a worker. That hardened his resolve, made him a man of the people and later let him enter the ranks of the Soviet party hierarchy, which theoretically was supposed to stand for workers.

Nazarbayev started his “worker’s biography” at a metal plant in Dneprodzerzhinsk, in faraway Ukraine. The work was very hard – he worked next to melting cast-iron, with temperatures running as high as 1000 degrees Celsius just a few meters away. But this was a good “school of life” – Nazarbayev learnt to communicate in Russian like a Russian, he did see real life in the former Soviet Union.

“What are you doing to yourself, son?!” – his father Abish was terrified when the young Nursultan in his early 20s returned to Kazakhstan and showed father his workplace at the metal plant in Temirtau. “It is a real hell! Run away from here!”

Kazakhstan’s First President and chairman of the Nur Otan Party Nursultan Nazarbayev announced plans to nominate Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev as the Nur Otan Party’s candidate for the 2019 presidential elections on April 23, 2019 at the party’s congress.

Nursultan stayed. He loved his native mountains and he felt better next to his kinsmen, the free men of the land, former nomads. But Nazarbayev knew: his Kazakhstan needed industry. This was the future, this was life. So, his place was here, next to the industrial future. There was no way back, even though agriculture remained an important source of income and it would help the future independent Kazakhstan sustain itself through the immensely difficult 1990s. This is also part of Nazarbayev’s secret: never choose the easy way, face the difficulties now to prevent disasters in the future.

Nazarbayev switched to administrative work at the age of 29, in 1969. By that time, he had seven years of “hot metal work” behind him, and people would note it many times in the future, when he would become the prime minister of Soviet Kazakhstan, a position requiring knowledge in both industry and agriculture.

In the 1970s Nazarbayev grew from a regional leader in Karaganda region (this is the region where his Temirtau metal plant was located) to the very top of Soviet Kazakhstan’s government. In 1984 he became the prime minister. People would later remember this period as the “years of stagnation,” when Leonid Brezhnev’s ruling elite helped itself to the “fruits of developed socialism” without caring much about the people’s situation.

But it wasn’t a period of stagnation for Nazarbayev. Kazakhstan was getting its own industry, “the hen laying the golden eggs,” which will save it, when Kazakhstan becomes an independent state in 1991. Magnitogorsk, Karaganda Metallic Plant… Now the golden eggs are being laid for the Soviet budget. But Kazakhstan’s people will profit from them too, when times change. And Nazarbayev knew they would change.

He starts to see the world outside the Soviet Union. During a short vacation in his Komsomol work, he visited the youth festival in Helsinki, Finland. He saw that life could be… so different. Shopping malls and gas stations could be so much better than in the USSR, but people in the West could sometimes be so ignorant about life in his part of the world. Nazarbayev remembers how a Finnish girl could not believe he wasn’t a son of some Soviet boss until he showed her his callous hands of a metal worker. Yes, building bridges with the West will not be easy. But, in the end, human nature is friendly, and humane approaches will overcome ethnic (and historic) barriers. Nazarbayev knew it from the experience of his “multiethnic” early years.

Another part of Nazarbayev’s secret: he never betrays. In his life, he never betrayed people, ideas and countries – unlike many former Soviet citizens. When Nazarbayev was elected the President of Kazakhstan on Dec.1, 1991, the republics of Soviet Central Asia fulfilled their commitments to the Soviet Union long after the Baltics, Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova stopped fulfilling theirs. Nazarbayev fulfilled his commitments too, and even planned to sign a new Union Treaty with Gorbachev on Dec.9, 1991. It was the “troika” of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine that announced the end of the USSR and the formation of the so- called Community of Independent States on Dec.8, 1991. Kazakhstan became an independent state without a single shot fired, without violence, but with uncertainty ahead. The new country is born, but it is very rare that we see a smile on Nazarbayev’s face on the photos from that time. As usual, he was preparing for the worst…

Without trumpeting its successes, independent Kazakhstan under Nazarbayev went ahead of 90 percent of former Soviet republics in its economic and social reforms. Measures to attract foreign investment, which the neighbors are still trying to imitate – check. The pension reform, which Russia and Belarus are only starting to take seriously – check. The education reform, tri-lingual system of teaching (Kazakh, English and Russian languages are all supported and fostered in Kazakhstan) – check. Nazarbayev is polite and respectful in international politics, but he is always active and forward-looking at home: one reform after another, always keeping up to date with the world’s economic, scientific, ecological standards. And there is only one sphere where Nazarbayev language is rough, even abrasive. That is when he speaks about internal peace and stability in the country. “We won’t let turmoil in, even if someone wants it,” he said famously in 2015.

After ceding his position to younger leaders in 2019, Nazarbayev remained THE leader – primarily because of his moral authority. And when he said in the beginning of the coronavirus epidemic in the beginning of the year 2020 that the country should prepare for the worst – oil prices plunging, economic downturn, new burdens on the healthcare system – people knew that he was right. But his strategy of always preparing for the worst worked again. The country is recovering, as always.

The author is Dmitry Babich, a Moscow-based journalist with 30 years of experience of covering global politics, a frequent guest on BBC, Al Jazeera and RT.