ASTANA – The recent 2018 Central Asian Documentary Film Festival (CADF) in Almaty explored themes of environment, identity and migration in the region.

The documentary festival was part of Almaty’s fifth Clique Film Festival and included short and feature-length film directors from Canada, Germany, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, the Netherlands and Russia. They were evaluated by jury members, including Oxford Brookes University lecturer Rico Isaacs, International Documentary Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) Bertha Fund head Isabel Fernandez, film director Tinatin Gurchiani and IDFA programmer and producer Viktoriya Kalashinkova.

Zaheed Mawani’s documentary “Harvest Moon” was awarded best picture, which also recognised the work of operator Sebastián Hiriart, and the best director award went to Denis Shabayev for his documentary about a young Tajik, “Not My Job.”

“‘Harvest Moon,’ a film about a family that harvests walnuts, was shot beautifully and told in a way in which it was a universal story about a family, which I think is important – to not present Central Asia as an obscure and oriental ‘other’… It could have been a story told anywhere in the world, but Central Asia was the setting,” said Isaacs in an exclusive interview with The Astana Times.

In addition to considering technical aspects such as cinematography and character development, the jury paid close attention to the films’ substantive content.

“To what extent do you have an emotional relationship with what you are watching?” he asked regarding the jury’s criteria for awards. “There was a very charming protagonist in the documentary ‘Songs of Abdul’ about a Tajik from Pamir who goes to work in Moscow. He really won you over and was a joy to watch. Life is difficult for him, but through song and dance, he manages to accentuate the positives in life.”

“One key theme [across the documentaries] was the question of migration, explored in different ways,” he added. “In terms of labour migration, there were a few films about Tajiks migrating to Russia for work, the difficulties that imposes upon them and what that tells us about Tajikistan and its economic situation. There were also two films about the return migration of Germans who had left Kazakhstan after the collapse of the Soviet Union and come back 25 years later and were exploring the things that had changed.”

Isaacs sees a space for Central Asian content produced by Central Asians themselves, which may facilitate a more balanced representation of life in the region rather than the predominant focus on drug trafficking, rural life in the mountains and Aral Sea degradation.

“Another element to life in Central Asia is that lots of people live in cities. In fact, Almaty has grown immensely over the last 20-25 years because people were migrating to the city looking for work and there could be stories told about urban life in that way,” he said.

He singled out the documentary “Sing your Songs/in Kazakhstan,” about the Qazaq pop group Ninety One, as an insightful look into how Kazakhstan balances the global and the local.

“There’s a concept in cultural theory called hybridity, which is this idea that global influences arrive at a particular country and are then modified within that context with traditions and particularities,” he said. “I think that the band Ninety One is an example of that with their commitment to singing in the Kazakh language. But their influences are also global, and that does not necessarily mean Western, as their biggest influence is the K-pop movement in Korea. To me, they are an embodiment of this very abstract concept of hybridity in cultural studies.”

Local filmmakers, too, are balancing the global and the local in shaping the country’s cinema. Kazakh films produced in the mid-1980s-early 1990s have been particularly formative for recent Kazakh art house cinema, but there are challenges.

“Given the ways in which cinema is a global and universal medium, to carve out something that is distinctly Kazakh in cinematic language is a very difficult thing to do,” he noted.

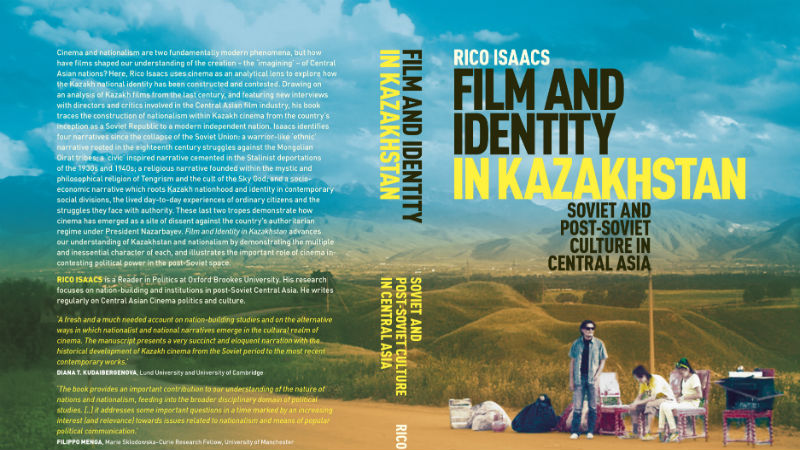

Film and Identity in Kazakhstan: Soviet and Post-Soviet Culture in Central Asia. Photo credit: brookes.ac.uk.

In his recent book “Film and Identity in Kazakhstan: Soviet and Post-Soviet Culture in Central Asia,” Isaacs relies on cinema as an analytical lens.

“Cinema reflects what is going on in society at any given time,” he said. “Since 2005, there has been an emergence of more [Kazakh] films with greater state funding, and the film studio Kazakhfilm became a joint stock company… With independence, important social questions emerged in Kazakhstan that were reflected in cinema, such as nation building, the country’s multi-ethnic demography, Soviet-era political repression and finding and defining what it means to be Kazakh… Watching these movies, representations of these questions seem to come out directly – in ‘Nomad,’ ‘Myn Bala: Warriors of the Steppe’ and ‘The Gift to Stalin’ – and indirectly – in ‘Racketeer’ or even ‘Kelinka Sabina’ (‘Bride Sabina’).”

Through analysing 20th and 21st-century Kazakh films and interviewing directors and critics, Isaacs identified four such interpretations of Kazakh nationhood and identity – ethnic, civic, religious and socioeconomic narratives rooted in Mongolian Oirat tribe conflicts; Stalinist deportations; the Tengrism religion and contemporary socioeconomic divisions, respectively.

“These narratives demonstrate that there is no correct or single reading of Kazakh national identity, as there is no right reading of any nationality around the world. Nations are made up by different groups, interests and classes, each with different ways of understanding and interpreting nationhood. Thus, how we understand national identity and the ways nations come to being is ultimately through social construction,” he added, encouraging additional narratives to be found through film analysis.