ASTANA – The shrinking of the Caspian Sea is no longer just an environmental issue but an economic one. While sea levels have fluctuated for over a century, recent decades have shown a steady decline, driven by climate change and human activities, according to Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources.

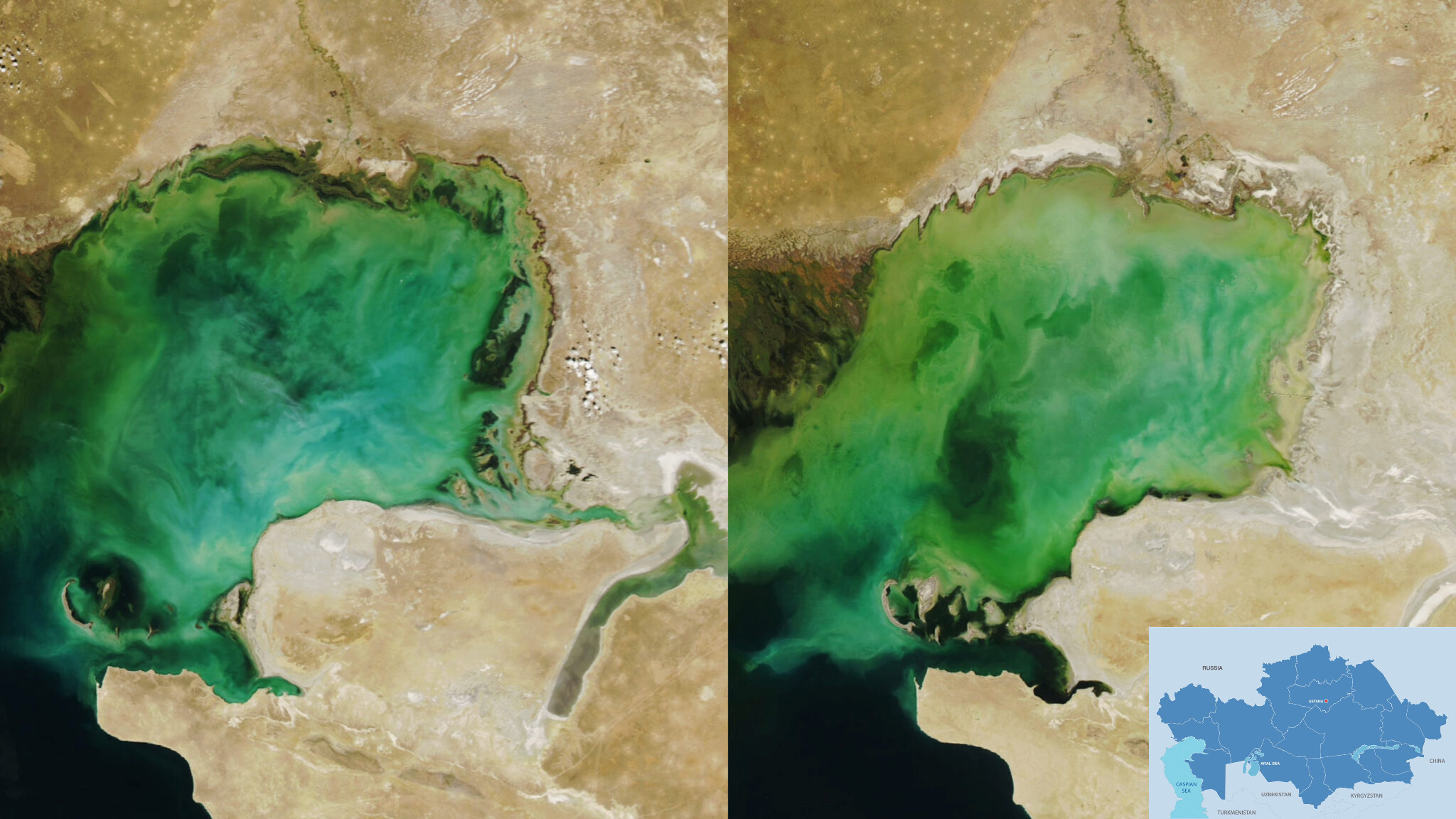

NASA satellite images of the Caspian Sea as of September 2006 (L) and September 2022 (R). Photo credit: NASA Click to see the map in full size. The map is designed by The Astana Times.

A new phase of shallowing began after a sharp rise in the mid-1990s. Between 2006 and 2024, sea levels fell by more than two meters. In the first half of 2025, the average level in Kazakhstan’s sector dropped to minus 29.3 meters, with the lowest readings recorded in the eastern Caspian. Over the past five years, levels in the Northern and Middle Caspian have declined by nearly one meter.

Climate change and human impact

Laura Malikova, chair of the Association of Practicing Environmentalists, noted that dredging operations conducted by the North Caspian Operating Company (NCOC) and its contractors to support navigation and cargo deliveries have contributed to rapid shallowing.

Laura Malikova, chair of the Association of Practicing Environmentalists. Photo credit: Kazinform

“Photos and videos clearly show how far the water has retreated. The northern Caspian is becoming shallow at an extremely rapid pace,” said Malikova, as quoted by the Kazinform news agency.

According to the Kazakh ministry, climate change remains the main driver of the long-term decline. Precipitation in the Caspian region is decreasing, while evaporation is increasing. Because of its continental climate and its distance from the oceans, the region is particularly vulnerable to global warming.

From 1976 to 2024, global temperatures rose by an average of 0.19 degrees Celsius per decade. In Kazakhstan, the increase was 0.36 degrees, while in the Caspian region it reached 0.51 degrees, nearly three times the global average.

“It is crucial to conduct economic activity, from oil production to other sectors, in strict compliance with environmental and technological standards,” Malikova said, warning against repeating the Aral Sea disaster.

Economic pressure on coastal regions

The economies of Caspian coastal regions remain heavily dependent on logistics and oil production, creating a challenge: expanding economic activity increases environmental pressure, while falling water levels cause economic losses.

Lower water levels of the Caspian Sea complicate access to offshore fields, increase transportation and maintenance costs, and reduce vessel carrying capacity.

According to the Mangystau Region akimat (administration), the greatest losses are felt in oil and gas production, shipping and coastal infrastructure. Lower water levels complicate access to offshore fields, increase transportation and maintenance costs, and reduce vessel carrying capacity.

At the Aktau port, tankers now carry up to 3,100 tons, feeder vessels up to 300 tons and grain carriers up to 1,200 tons. Re-berthing grain vessels costs around one million tenge (US$1,957) per ship, while annual dredging costs reach roughly 400 million tenge (US$782,870).

Dredging at the Kuryk port has increased channel depth to around seven to eight meters. In Aktau, the average depth is 4.5 meters, below the 6.5-7 meters needed for full operations. Dredging began in 2025 and is expected to restore full capacity.

Effects and risks

Retreating shorelines are also affecting tourism. Smaller beaches and declining visual appeal have forced developers to revise projects and increase infrastructure spending. Officials say the sector is shifting toward ecotourism, cultural routes, and desert and adventure tourism.

Public health risks are increasing as dried seabed areas become sources of dust and salt storms that carry pollutants, including oil residues and heavy metals. These storms increase the incidence of respiratory illnesses and strain the health care system.

The shrinking sea also threatens Aktau’s water supply. Reduced water intake affects drinking water, heating and electricity generation.

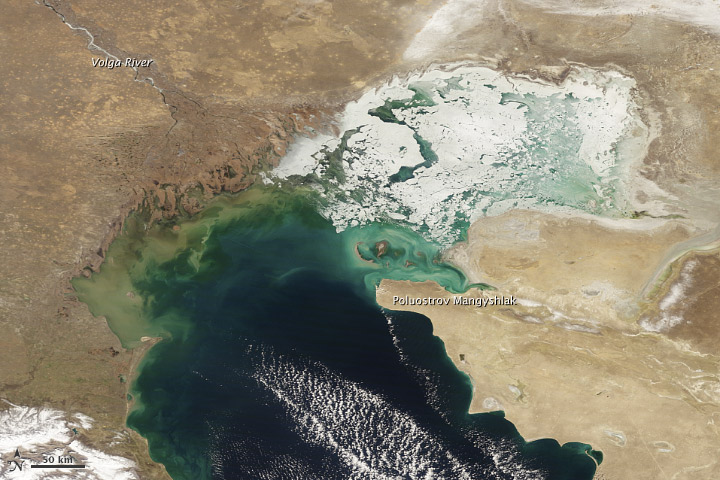

The northern part of the Caspian Sea. Photo credit: NASA Earth Observatory.

“Due to the shallowing of the Caspian Sea, the volume of water entering the Thermal Power Plant (TPP)-1 and TPP-2 channels is decreasing, and accordingly, water production is also declining,” said the akimat. Several projects are underway to deepen and extend the channels.

The ecosystem and the fishing industry are also under strain.

Malikova highlighted that dredging in the northern Caspian by NCOC disrupted feeding grounds for fish and seals, accelerating shallowing.

“At the same time, work in the ports of Kuryk and Aktau is a necessary measure to ensure navigation and infrastructure operations,” she said.

The Mangystau administration is supporting fisheries through marine cages, fish farms, modern vessels and annual restocking of the Caspian Sea.

Regional cooperation

Kazakhstan is working with other Caspian states under the Tehran Convention on marine environmental protection and has ratified four protocols covering oil pollution response, land-based pollution, environmental impact assessment and biodiversity conservation.

A new monitoring and data-sharing protocol is under discussion, along with a joint environmental monitoring program. Five Caspian countries are also developing a 2025-2035 action plan to address sea-level fluctuations.

The Regional Environmental Summit is scheduled to take place in Astana on April 22-24, and will include a panel dedicated to the declining Caspian Sea. The Caspian Sea Research Institute has been operating since September to monitor environmental conditions and conduct scientific studies.

Malikova noted that negotiations with Russia are essential, as many reservoirs now retain water that once flowed into the Caspian.

“In recent decades, many reservoirs have been built in Russia, such as Iriklinskoye, and a significant share of the water remains there. It is important to coordinate larger water releases through rivers such as Zhaiyk and other rivers to feed the northern Caspian,” she said.

She added that progress has been slow and that technical experts, not only politicians, should be involved in the talks.

The article was originally published in Kazinform.