Data often sounds distant and pale until it touches your background. Standing in front of installations built from statistics on femicide, violence, unequal pay, and education gaps, I felt something I hadn’t named aloud before.

Ayana Birbayeva

The exhibition “Tirek — The Thread of Her Life,” organized within the UN Women regional program in partnership with the Central Asian Alliance to End Gender-Based Violence and the UN Women office in Kazakhstan, brings these issues into a space where data becomes tangible.

Presented at the Almaty Gallery, the exhibition runs until Dec. 15 and invites visitors to immerse themselves in the lives of thousands of women, revealing the true essence of their existence through works by Central Asian female artists.

In Turkic languages, the word “tirek” means “support” or “backbone.” For me, this word has always had a personal resonance, even before I understood its meaning. Looking at the installations, I let myself listen to the stories I once thought would not move me, as they were stories I’d learned to hold at a safe distance.

One of 14 works presented in the gallery, “Mono,” was represented as a vibrant collage made of 226 children’s drawings, reflecting the lives of monoparent families in Kazakhstan. The drawings were collected during workshops in Taraz, where children were asked to draw their families. Each family was recorded as two-parent, large, or mono-parent, and the drawings were woven into three collages based on these categories.

“Mono” by Galina Shumilina and Maria Krapp (Kazakhstan) is a vibrant collage installation featuring 226 children’s drawings, dedicated to mono-parent families in Kazakhstan. Photo credit: The Astana Times

Standing before “Mono,” I suddenly remembered my own childhood drawings on the same topic. I remembered how confidently I drew my small family – my mother, my sister, and me – without ever feeling that anything was missing. As I stayed longer in front of the collage, the statistics behind the artwork began to sink in, allowing me to see the case in a broader context.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, Kazakhstan was home to over 780,000 mono-parent families in 2021, 1.5 times more than in 2009, while 87% of them were mothers with children. Precisely, one in five children grows up with a single parent, as the art study highlights that such children should not face bias.

I was raised in a single-parent family, but I didn’t realize this immediately. As a child, I never felt less than or incomplete. When you’re taking your first steps in life, you don’t read your path through definitions. The realization came much later, through the subtle details that adulthood teaches you to notice: the early wrinkles on my mother’s face, her constant hurry, the endless work she carried alone, and her determination to ensure I never felt different from children with “full” families.

Back then, I didn’t know she was my “tirek.” I didn’t know I would spend years searching for support in places where tradition told me it should be only to learn, again and again, that the pillars I leaned on most were built by women.

Adolescents tested this understanding. In English or Kazakh classes, whenever we had to describe our families, classmates hesitated when they learned there were only girls in mine. Their curiosity wasn’t unkind, but it carried the echo of a narrative I hadn’t yet learned to name.

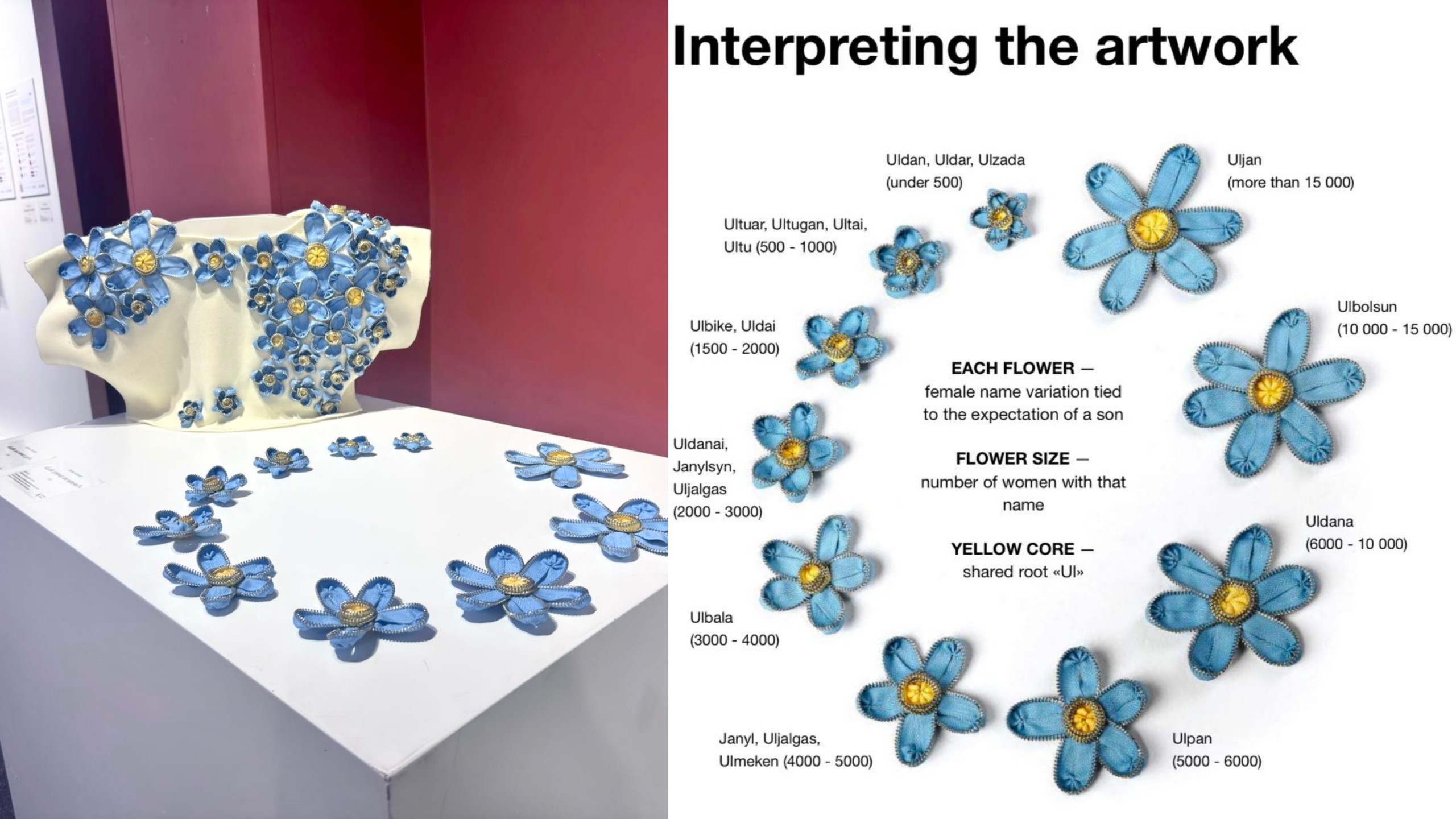

“QizUl: girl or boy?” by Zhanna Assanova (Kazakhstan)

“QizUl” is a conceptual piece of jewelry that combines the words “qiz” (daughter) and “ul” (son), rethinking the tradition of preferring sons and emphasizing the equal value of each child. Photo credits: The Astana Times, UN Women

Later, I met boys who said they could never be with a girl from a “broken” family, as if a woman’s worth depended on a father in the house, as if daughters raised by mothers alone were somehow less well-mannered, less deserving, less whole. But as I grew older, I met girls who did have fathers and carried wounds far deeper than mine. Their stories of anger and control reshaped everything I thought I knew about protection, love, and the myths that surround both.

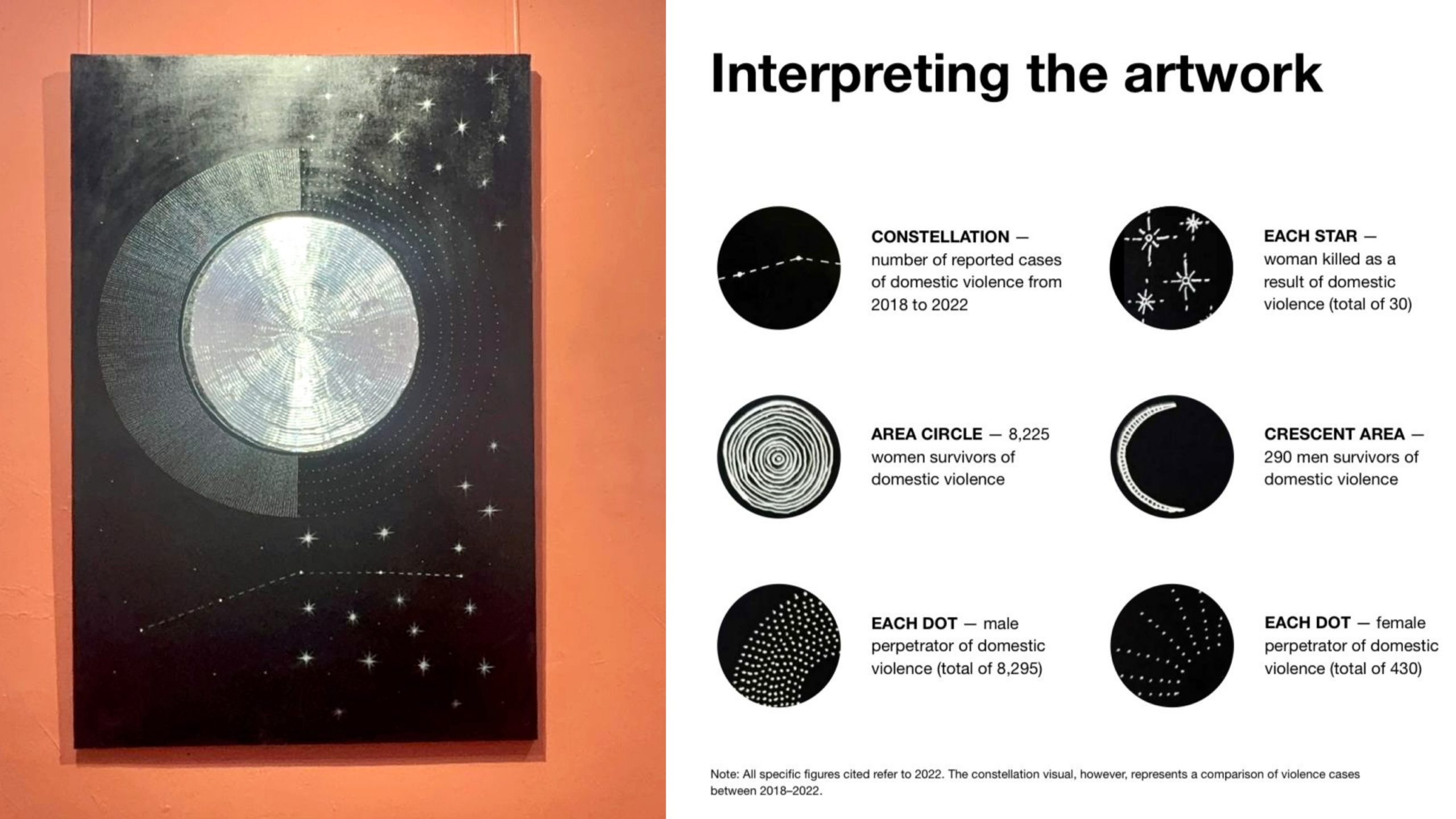

Elvira Sharif’s painting “Voices of Silence” conveyed the stories of those who couldn’t break the silence surrounding domestic violence in the Kyrgyz Republic. Standing before it, I felt as if the texture itself echoes the complexity of stories so many women never speak aloud. Each relief line symbolizes thousands of lives shaped by domestic abuse, with minimalist lines and scattered dots emphasizing how invisible the issue often remains. The small stars scattered across the surface pay tribute to those whose lives were cut short.

The central contrast of the painting struck me the most, containing a large, overwhelming circle representing the number of women who survived domestic violence, and beside it, a tiny, nearly imperceptible mark showing the number of male survivors. A constellation-shaped graph depicts the reported cases from 2018 to 2022, showing a 38% increase and reaching nearly 10,000 cases in 2022. According to the data provided, women accounted for 97% of the victims, and 95% of perpetrators were men.

“Voices of Silence” by Elvira Sharif (the Kyrgyz Republic) is a relief painting that combines data and art to break the silence about the problem of domestic violence. Photo credits: The Astana Times, UN Women

Standing in front of this artwork, I felt the weight of stories my friends once hinted at, the silence behind their eyes, with the emotional landscapes they navigated. Perhaps that’s why the exhibition felt so personal, as it carries recognition and understanding that the private stories we carry within ourselves are shared by so many others. Data art added something rare to the global problem of injustice and underestimation, giving weight, color, and texture to numbers.

The exhibition revealed the systems we need, the support women deserve, and the structures that should hold us rather than forcing us to bend around gaps that shouldn’t exist. But it also reminded me of another truth: sometimes support is not given. Sometimes it is created by mothers, sisters, daughters, by women who learn to speak up and stand together.

In that sense, the exhibition becomes something between art and therapy, the place where recognition meets healing, reminding us that the hidden can always become visible and big enough to care about.