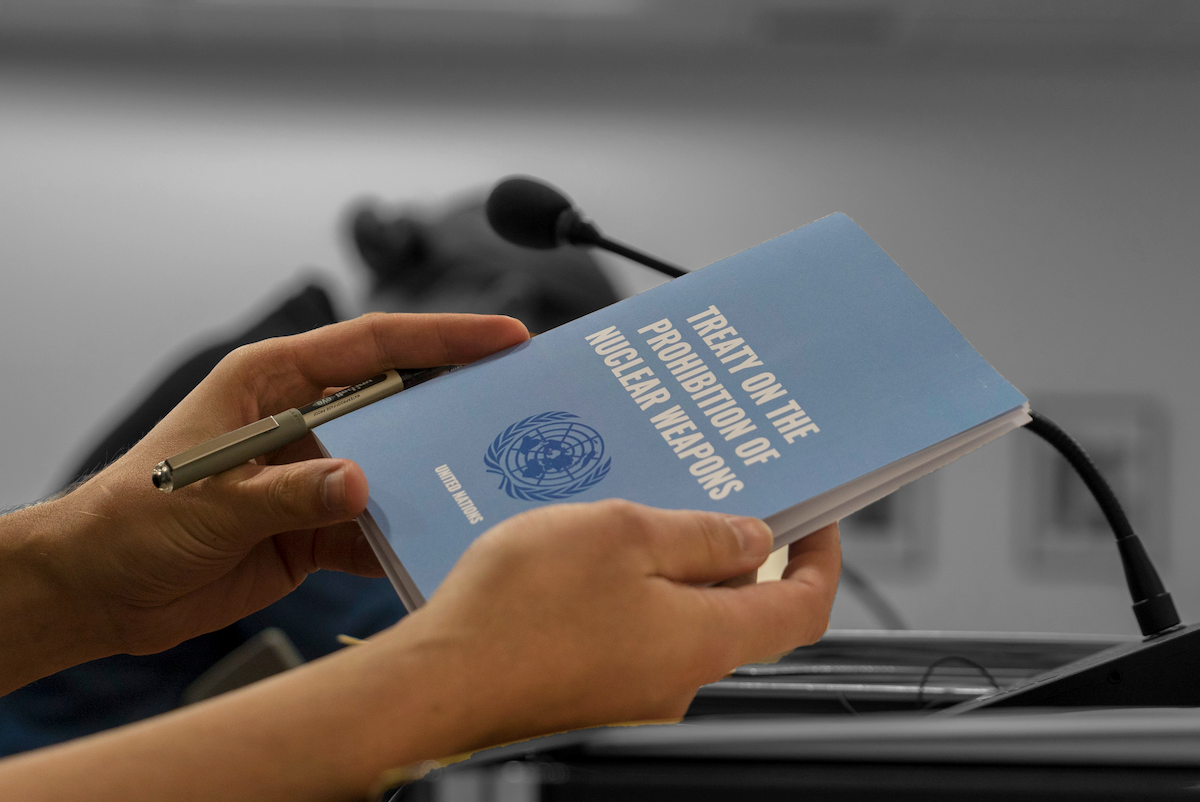

ASTANA — Community leaders, researchers and practitioners gathered for a roundtable on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear testing in Vienna on Nov. 27, examining what the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) can deliver today and what steps are required to secure justice for affected communities.

Photo credit: icanw.org

The event, hosted by Dialogbüro Vienna, Steppe Organization for Peace (STOP) and Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) Kazakhstan, focused on recognition, remediation and the future of inclusive disarmament.

Kazakhstan’s experience remained a central reference. Guided by the Nevada-Semei movement, the country closed the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site in 1991, renounced the world’s fourth-largest nuclear arsenal, and continues to pursue justice under Articles 6 and 7 of the TPNW, which require states to provide victim assistance, remediate contaminated environments and cooperate internationally to support affected populations.

Humanitarian principles and the TPNW framework

Panelists stressed that translating the TPNW’s humanitarian principles into practice requires moving from symbolic commitments to structural, long-term implementation.

Gaukhar Mukhatzhanova. Photo credit: UN Photo/Evan Schneider

Gaukhar Mukhatzhanova, a director of the International Organizations and Nonproliferation Program (IONP) at the Vienna Center for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation (VCDNP), said Articles 6 and 7 reflect decades of survivor-centered advocacy and highlight the need for international cooperation, particularly since many state parties are developing countries with limited resources.

“There is no trust fund yet, and there are both economic and political reasons for that,” said Mukhatzhanova, emphasizing the diversity of views on who should contribute, how assistance should be allocated and who should participate in decision-making.

“One of the most sensitive questions was who should be allowed to contribute to the trust fund and how decisions on assistance should be made. States had very different views on the degree of involvement for affected communities, NGOs and academia in running the fund. Another concern was how the impact of assistance would be monitored and assessed in practice,” she said.

Mukhatzhanova said that several state parties are cautious about creating new financial obligations, even though contributions to the proposed trust fund are intended to be voluntary rather than mandatory. Affected communities favor opening the fund to donors outside the treaty, yet this raises concerns about influence, optics and political sensitivities, particularly if contributions come from states that have not joined the TPNW. Contributions from neutral countries such as Switzerland would likely be welcomed, but support from military allies of nuclear-armed states could be politically sensitive.

Alicia Sanders-Zakre. Photo credit: ICAN

“The co-chairs of the working group will still have the task of continuing consultations and bringing something to the Review Conference, scheduled for November 2026, that could be transformed into an actual decision on the establishment of the fund,” she said.

Alicia Sanders-Zakre, a policy and research coordinator at the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), echoed the need for inclusive and transparent implementation.

“We are working to eliminate nuclear weapons worldwide, and our main tool to do that is the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. (…) There aren’t really a lot of international treaties, particularly in disarmament, in nuclear weapons law, where civil society coalitions, like ICAN, are able to have, not quite an equal seat at the table, but to be very involved in the process to decide how the treaty will be implemented,” said Sanders-Zakre.

Véronique Christory. Photo credit: ICRC

She added that these commitments require states to work transparently, integrate gender considerations and engage closely with academia, affected communities and civil society.

Véronique Christory, a senior arms adviser for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), shared the sentiment, adding that humanitarian perspectives must remain central amid escalating geopolitical tensions.

“Why is it important to focus on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons? Because they are the benchmark against which the moral, ethical and legal acceptability of the weapon is to be judged,” said Christory.

“We cannot allow a repetition of the dark part of the dark part of our past. The ICRC message, therefore, is clear, and we have been very outspoken about what we cannot prepare for, what we cannot respond to, we must prevent,” she added.

Nuclear legacies: Kazakhstan and Marshall Islands

The panel also examined the long-term consequences of nuclear testing in Kazakhstan and the Marshall Islands.

Alisher Khassengaliyev, a founding member of STOP, outlined the scale of nuclear harm in Kazakhstan. The Semipalatinsk test site saw more than 450 tests across 18,000 square kilometers, leaving long-term environmental and health consequences for nearby communities.

He noted that although Kazakhstan adopted a law on social protection for survivors in 1992, significant barriers persist, including outdated eligibility criteria, fragmented governance, and limited decision-making roles for affected communities.

“Participation in shaping the policies by affected communities and civil society, unfortunately, is largely just advisory. Survivors and local organizations are consulted, and it’s true, it’s a fact, but barely empowered to shape policies within the framework,” he said.

STOP’s recent work includes drafting amendments to the 1992 law and proposing sustainable development programs for affected regions. Khassengaliyev said Kazakhstan should ensure that the future trust fund strengthens inclusive governance and prioritizes human-centered services.

“As we approach the 35th anniversary of the polygons’ closure, we have a very straightforward and clear choice,” he said.

“We can continue to celebrate our ‘disarmament leadership’ while allowing the gap between the leadership and delivery to persist within our country. Or we can use tools such as the TPNW and hopefully the International Trust Fund to align our international commitments with concrete, measurable improvements in the lives of those who still live with nuclear harm,” said Khassengaliyev.

Benetick Kabua Maddison, an executive director of the Marshallese Educational Initiative. Photo credit: ICAN

Benetick Kabua Maddison, an executive director of the Marshallese Educational Initiative, described similar long-term effects of U.S. testing in the Marshall Islands.

“This purposeful oversight disregards the human rights of the Marshallese people, and it’s a grave injustice. (…) These are hard, well-known facts, yet the United States refuses to acknowledge them adequately, said Maddison.

“These disruptive devices are engineered as tools of terror, designed to promote hatred and create division among nations and people,” he added.

Maddison said that the proposed trust fund could support health care, environmental restoration, education and community resilience, but only if frontline communities are involved in its design and governance.