ASTANA — Friendships take many forms, but when they develop between the great minds of two nations, they transcend the personal, forging a bond that unites nations and fosters respect for the literature and culture of others.

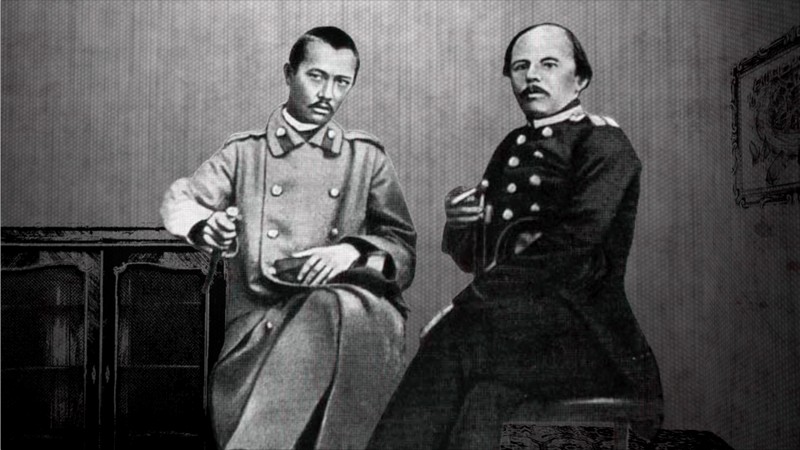

Kazakh scholar and ethnographer Shokan Ualikhanov (left) with Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky. Archive photo.

Such was the friendship between Kazakh ethnographer Shokan Ualikhanov and Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky, known for novels such as “The Brothers Karamazov” and “Crime and Punishment.” Their friendship flourished primarily through the letters they exchanged over a six-year period. Written with genuine affection and intellectual spark, those letters give rare insights into the meeting of creative, sensitive, and genuine minds.

This year, Kazakhstan marks 190 years of Ualikhanov, whose pioneering accounts of Kashgar, Dzungaria, and Eastern Turkestan became invaluable sources for understanding the region. Beyond scholarship, Ualikhanov served as a voice for his people, advocating for their cultural and historical legacy within the broader Russian Empire.

How did they meet?

Ualikhanov and Dostoevsky first met in 1854 in Omsk at the home of military engineer Konstantin Ivanov, a mutual acquaintance. After his release from the Omsk prison, Dostoevsky lived in the Ivanov’s house for a month. At that time, Ualikhanov had just graduated from the Siberian Cadet Corps and served as an aide to Gustav Gasfort, the governor-general of Western Siberia.

Born 14 years apart, in 1821 and 1835, Ualikhanov and Dostoevsky nevertheless found an immediate sense of companionship and understanding with each other.

Perhaps, it was under the influence of this friendship that Dostoevsky later wrote in his “A Writer’s Diary”: “We will be the first to declare to the world that we do not want to achieve our own success by suppressing the personalities of nationalities foreign to us, but, on the contrary, we see it only in the freest and most independent development of all other nations, and in brotherly unity with them, complementing each other, grafting their organic characteristics onto ourselves and giving them branches for grafting from ourselves, communicating with them in soul and spirit, learning from them.”

Their letters

The two literary writers wrote letters to each other that now reveal rare insights into their friendship – sometimes affectionate, intimate, and supportive.

Ualikhanov’s letter to Dostoyevsky, 1856. Photo credit: tramplin.media

To this day, only four letters from Ualikhanov and one letter from Dostoevsky have remained. Researchers believe that most of their letters have been irretrievably lost or have not yet been found in the archives. Their correspondence lasted for almost six years.

Shortly after their first meeting in Omsk, Dostoevsky was dispatched to Semei for indefinite military service. A year later, the two friends reunited there.

“It was very, very difficult to part with people whom I had grown so fond of and who were also kindly disposed towards me,” Ualikhanov wrote Dostoevsky in 1855.

“I enjoyed those few days spent with you in Semipalatinsk [now Semei] so much that now all I can think about is how I might visit you again. I am not skilled at writing about feelings and dispositions, but I think that is unnecessary. You, of course, know how attached I am to you and how much I love you,” he wrote.

Dostoevsky, being a man with a wealth of life experience, wrote back, giving his young friend valuable advice on his future career:

“In seven or eight years, you could arrange your destiny in such a way that you would be extremely useful to your homeland. For example: is it not a great goal, a sacred cause, to be almost the first among your people to explain to Russia what the Steppe is, its significance, and your people’s relationship to Russia, while at the same time serving your homeland by enlightening the Russians about it? Remember that you are the first Kyrgyz [Kazakh] to be educated in the European manner. Fate has also made you an exceptional person, giving you both a soul and a heart… And anything is possible, rest assured,” wrote Dostoevsky.

A mutual photo

Given the intimacy of their letters, it is surprising to realize that the friends met only a few times. One of their last times together was when Ualikhanov had just returned from a trip to Kashgar. The famous expedition was undertaken in 1958 with a caravan of 43 people, 101 camels, and 65 horses. The mission allowed Ualikhanov to thoroughly document geographical features, as well as customs and languages of the region, which later attracted increased attention from the capital of the Russian Empire.

Monument to Ualihanov and Dostoevsky in Semei. Photo credit: godliteratury.ru

On his way to Omsk, Ualikhanov stopped in Semei on official business and naturally took the opportunity to visit his friend Dostoevsky, who had by then received permission to return from exile to Central Russia.

There is a black and white photo of them. The two are sitting still, Ualikhanov gripping a knife, while Dostoevsky casually holds a cigarette. The image, captured in 1859, is quiet and intimate. They sit closely, their legs almost touching.

Interestingly, no photographs exist of Dostoevsky alone with his brother Mikhail, his wife Anna, or even his children. The sole exception is a rare double portrait with Ualikhanov.

A sculptural composition was created based on this photograph and installed near the building of the Dostoevsky Literary Memorial Museum in Semei.

Ualikhanov’s work

After that photo, their paths diverged. Ualikhanov went to St. Petersburg where he worked tirelessly on the report on the Kashgar expedition. Promoted to staff captain, he served first in the general staff and then, by imperial decree, in the Asian Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

During this period, Ualikhanov wrote his major works – “Essays on Dzungaria,” “Description of Eastern Turkestan,” “Abylai,” “Shuna Batyr,” “Tarikhi Rashidi,” and “Notes on the Kokand Khanate,” acting, as Dostoevsky urged, as an advocate for his people.

However, the humid climate of St. Petersburg took a toll on his health, and by spring 1861, suffering from tuberculosis, Ualikhanov returned on medical advice to his father’s village of Sarymbet in Kokshetau.

“My dear friend, Fyodor Mikhailovich [Dostoevsky]. You probably think that I have long since died, but I am still alive, and this letter is proof of that… I want to get the position of consul in Kashgar, and if not, I will resign and serve in my own district by election. In Kashgar, I would receive a good salary, the climate is good, and perhaps my health would improve. If that doesn’t work out, the steppe won’t be bad either,” Ualikhanov wrote Dostoevsky on Jan. 14 in 1862.

But these plans were not destined to come true. Ualikhanov died in 1865 from tuberculosis, before reaching the age of 30.