Editor’s note: Discover Kazakhstan is a column dedicated to exploring the rich cultural heritage and natural wonders of the country. Each article explores various aspects of Kazakh life and history, offering insights and stories that highlight their unique significance.

Apple city

“A good name is better than wealth” says a Kazakh proverb. As odd as this adage may sound when discussing Almaty—whether when speaking of its history as a medieval city situated on the Silk Road, its significance as a strategic point for Timur’s regional expansion, its role as a winter stopover for nomadic tribes, or its status as a Cossack stronghold—it is the name itself that has stood the test of time, enduring earthquakes, invasions, and numerous changes. The city’s name has continued to live its own life even through periods when habitation in it was temporarily interrupted, and the name of the city echoed in the courtyards of the Great Mughal Empire and in the Catholic monasteries of medieval Europe, though for entirely different reasons.

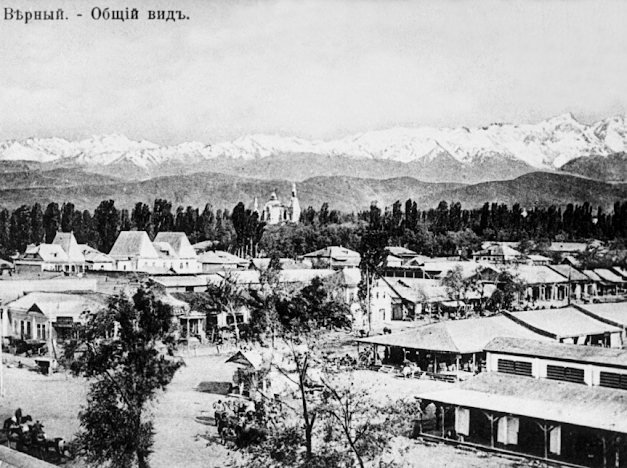

City of Verny. Photo credit:CGA KFDG RK

“After the Russians occupied the Zailiisky (Trans-Ili) Valley, a fortress named Vernoye was established on the site where the medieval city of Almaty once stood, renowned for its trade and serving as a station on the caravan route for many peoples, including Genoese merchants traveling to China,” wrote Russian scientist Nikolai Sorokin about his journey to the Tian Shan Mountains in 1884. In addition, Genoese merchants returning from China also brought back fragmented information about Almaty to Europe, including tales of Saint Matthew’s relics stored in a Nestorian church. The curious minds of the listeners logically connected these two things because ‘Almaty’ sounded similar to ‘Matthew’ in Arabic but with the definite article ‘al.’ The myth about Saint Matthew’s relics also eventually faded away when it became clear that it was actually referring to the Apple City.

Verny city

In 1867, the Semirechye region (Jetisu, the Land of Seven Waters, in Kazakh) was formed as a part of the Russian Empire, and Verny began to emerge as its administrative center. The city planning committee developed a layout with a standard rectangular grid of blocks for the nineteenth century. The streets were connected to the irrigation system, and thus the direction of the streets was determined by the slope of the terrain. The transverse latitudinal streets ran almost precisely in the east-west direction, parallel to the mountain ‘countertops.’ The longitudinal meridian streets descended from south to north at an angle of about four degrees. The orientation of the rectangular blocks to the cardinal directions unexpectedly brings Almaty closer to New York, but if the directions ‘up’ and ‘down’ are determined by the traditional orientation of north and south on the map in Manhattan, it’s the opposite in Almaty. ‘Up’ is what is higher in terms of elevation, toward the mountains located in the south.

Torgovaya street. Verny. 1914. Photo credit: CGA KFDZ RK

A main irrigation canal connected to the Malaya Almatinka River was laid along the upper of the latitudinal streets, from where water naturally flowed into the canals on other streets. Thanks to a well-thought-out irrigation system and rules requiring homeowners to plant trees on the street opposite their plot, the city quickly became very green. These early features, such as polycentricity, a rectangular grid of small elongated blocks, and an abundance of greenery, still exist in, and are characteristic of, the core of Almaty, but there are hardly any buildings from the nineteenth century left.

Alma-Ata

Transformed into the capital of Soviet Kazakhstan, Almaty was thrust into the limelight of Soviet urban planning and architectural ambition. This era saw the city reshaped by massive resettlement projects designed to accommodate a mix of evacuees and deportees from across the Soviet Union. Architecturally, Almaty became a showcase of Soviet ideologies—from the monumental Stalinist styles to the functionalist approaches of constructivism.

The Governor General’s house. The city is Verny. 1894. Photo credit: Wikipedia Commons

These developments were accompanied by significant demographic changes. The influx of non-native residents diluted the ethnic Kazakh population, creating a melting pot of cultures and identities. This blending, while enriching, also posed challenges in maintaining the Kazakh cultural heritage.

Almaty

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union the city reverted to its historical name, Almaty, in a symbolic move that marked a broader shift towards reclaiming its Kazakh identity.

I. Budenovich. Academy of Sciences of the Kazakh SSR. 1969. Photo credit:RIA

While it lost its status as the capital in 1997, Almaty today remains the country’s largest city and a major cultural and economic hub. The city faces challenges related to uncontrolled growth and environmental concerns, but it also boasts a rich architectural heritage and a growing appreciation for its historical identity.

One of the synonyms of the modern Almaty is Medeu. This huge and unique open-air arena was inaugurated in 1972 as an instant-classic Socialist Modernism set amidst a scenic alpine backdrop, a concrete complex of hotel rooms, box seats, and bandstands surrounding a 10,500-square-meter ice field. Medeu’s ice was legendary, frozen with such technical sophistication from pure mountain water that it could be skated upon with stunning speed, and the arena became known as the ‘factory of world records’ for speed skating. To this day, tourists from the Netherlands, a nation of speed-skating fanatics, make pilgrimages to touch the frozen course of champions.

Medeu Alpine Skating Ring. Photo credit: Alamy

Based on an original article by Anna Bronovitskaya, an architectural historian and the co-author of the book “Alma-Ata: Architecture of Soviet Modernism in 1955–1991” and Dennis Keen, a Kazakh language instructor at Stanford University and the author of the Walking Almaty and Monumental Almaty projects.

The full article can be found on the Qalam project website.