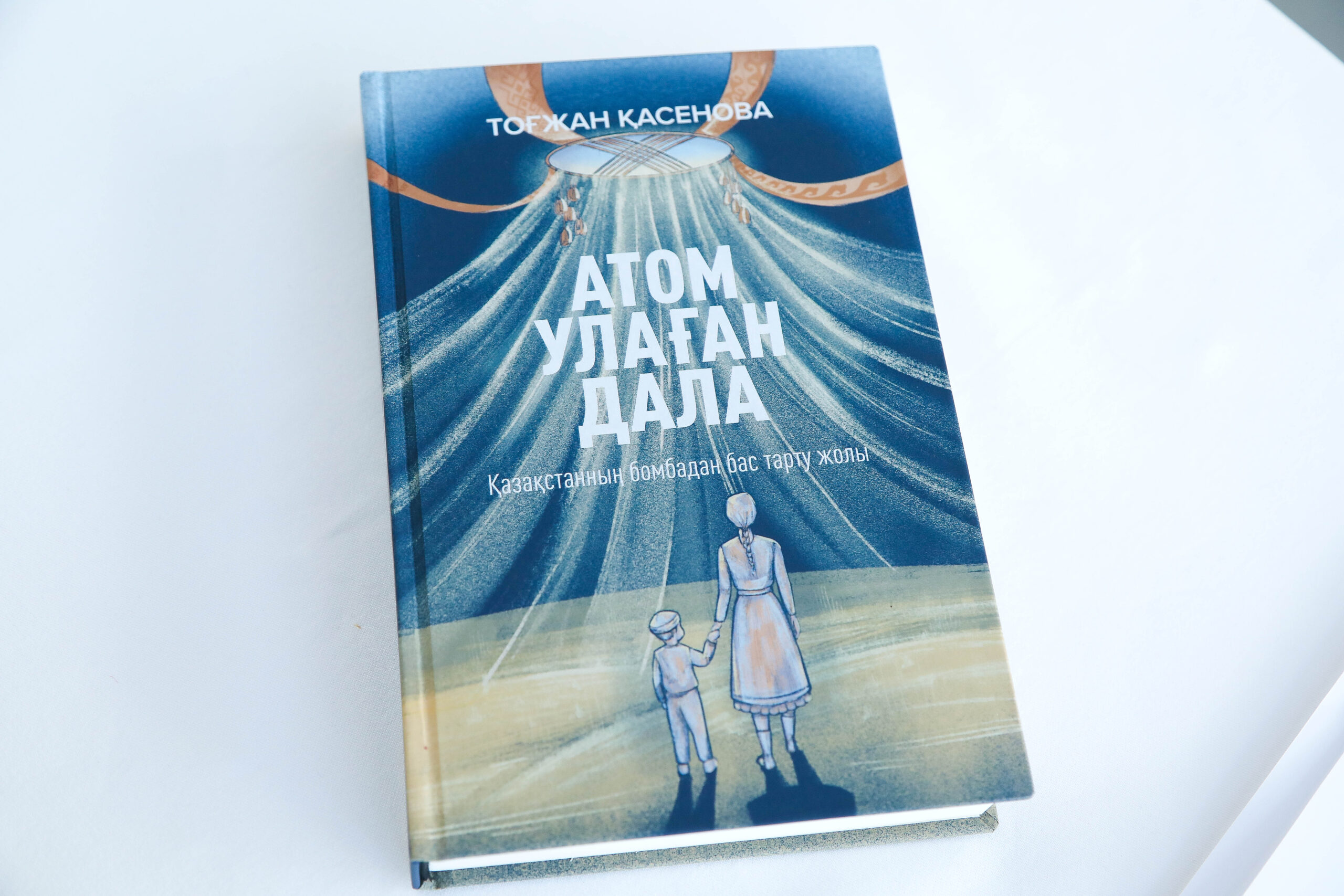

ASTANA – The Kazakh capital of Astana hosted the presentation of the Kazakh language edition of the book “Atomic Steppe: How Kazakhstan Gave Up the Bomb” written by prominent nuclear non-proliferation expert Togzhan Kassenova on Sept. 29. It tells the story of how Kazakhstan navigated through multiple challenges after the collapse of the Soviet Union emerging from once a nuclear testing ground into an independent and nuclear-free global leader in denuclearization.

The original book was published in February 2022. The Kazakh language edition is available for free. Photo credit: FES Kazakhstan

Initiated by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation in Kazakhstan, the Kazakh language translation, the result of the month-long work, seeks to raise greater awareness of the devastating consequences of nuclear testing and give power to Kazakh voices. The presentations are also scheduled to be held in Semei on Oct. 4 and in Almaty on Oct. 6.

Kazakhstan, the Central Asian nation with a territory nearly the size of Western Europe and a population of 19 million, voluntarily dismantled the nuclear arsenal that it had inherited following the collapse of the Soviet Union back in 1991. It was the world’s fourth largest at the time, including 1,040 nuclear warheads for 104 SS-18 intercontinental ballistic missiles and 370 nuclear-tipped cruise missiles.

Kassenova, a Washington D.C.-based senior fellow at the Center for Policy Research and a nonresident fellow in the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, has remarkable expertise in the nuclear politics, weapons of mass destruction nonproliferation, strategic trade controls, sanctions implementation, and financial crime prevention. Photo credit: FES Kazakhstan

The population in Kazakhstan knows the horrors of nuclear weapons well, as the Semipalatinsk test site located in the country’s once remote eastern part, just some 120 kilometers from Semipalatinsk (now Semei), had served as the site for more than 450 nuclear tests conducted by the Soviet authorities from 1949 to 1989 with more than 1.5 million people ending up being impacted by the tests. To this day, local residents, of the first and second generations, still suffer the health consequences.

Opening the event, FES Regional Director to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan Christoph P. Mohr said that the book is “not just a great piece of work but an intimate story and urgent lesson for global security.” He emphasized the significant contribution that the Kazakh story and the Kazakh voices, including those coming from the emerging generation of younger people, are making to the nuclear non-proliferation discussions on the global stage.

Kazakh civil movement activists gathered to demand a nuclear test ban at the Semipalatinsk test site in August 1989. Photo credits: armscontrol.org.

Kassenova, who has recently received the Dostyk (friendship in Kazakh) state award, said she had personal reasons for writing the book. Her father’s family lived in the city of Semipalatinsk, which explains her affinity for the region and for the hardships it had faced and continues to face.

Her father, Umirserik Kassenov, who was the first director of the Kazakhstan Institute of Strategic Studies, participated in foreign policymaking in the early 1990s, including nuclear issues. Kassenova explains she felt a “personal responsibility” to write the book.

“When you work on nuclear politics, the impact of nuclear programs, you think you understand the magnitude, but nothing prepares you when you actually see the land that suffered from the test and people who suffered,” she said. “It is one thing to know that the test site was the size of a medium-sized country, it is another to see it with your eyes.”

Two things are striking when she visits the local villages. “First, there are hardly any old people. Second is that children who had nothing to do with nuclear tests have visible health issues,” she added.

Kassenova shared some untold details of how Kazakhstan eventually got rid of its nuclear inheritance. She noted the important role of the Nevada-Semipalatinsk international movement initiated by famous writer Olzhas Suleimenov after the information about radiation contamination became public.

Olzhas Suleimenov, poet and leader of the Nevada-Semipalatinsk movement. Photo credit: V. Pavlunin / Central State Archive of Film and Photo Documents and Sound Recordings

“Olzhas Suleimenov was a member of the Soviet parliament, he had a slot on TV and he used that to mention contamination and call those who care to come to the House of Writers [in Almaty]. It was February and freezing, but in the hall which could fit 400 people, there were 1,000 people,” she said. With no social media and internet available back then, the magnitude of the movement was staggering.

Almost seven months later, Kazakhstan would make a well-thought-out decision to close the test site, which sent the nation on a decades-long, yet powerful journey promoting global nuclear disarmament ideals until the present day.

“That decision was made after the leadership considered security interests as well as economic political and diplomatic priorities. It [preserving nuclear material] was incompatible with how it wanted to present itself to the world decision-makers. They understood it would preclude access to what the new country needed the most – security guarantees of sovereignty, foreign direct investments, access to financial institutions, and respect from the outside world. In a geopolitically challenging environment, security assurances were critical,” she said.

Almost 33 years later since the closure of the Semipalatinsk test site, Kassenova said that it still serves as a reminder that keeping the non-proliferation regime can be the best choice for statehood and sovereignty.

“It [Kazakhstan] gave up but received so much support from the outside to become the country it is today,” she added.

Attending the presentation, Arman Baisuanov, deputy director of the international security department at the Kazakh Foreign Ministry, said the book and its Kazakh language translation send a message that “lessons are carefully studied and passed to future generations.”

“Many things may never see the light due to the secrecy surrounding the nuclear program. But her [Togzhan Kassenova’s] meticulous work gives deserved justice to those who suffered from radiation,” he added, reiterating the strategic importance of nuclear non-proliferation efforts in the nation’s foreign policy.

The presentation of the Kazakh language translation of the book in the Kazakh capital comes just a week after President Kassym-Jomart spoke about the increasing importance of nuclear non-proliferation efforts at the United Nations General Debates in New York. Addressing world leaders from the highest international rostrum, he expressed concern about the growing rivalry and rhetoric of the nuclear powers, as well as the lack of progress in the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) Review Conferences.