Zhambyl Zhabayev is not just a great Kazakh poet, he became almost a mythical figure, uniting very different epochs. Even his life span is unique: born in 1846 he died on June 22, 1945 – weeks after the defeat of Nazism in Germany. He had only eight months more to live to celebrate his 100th birthday, his centenary.

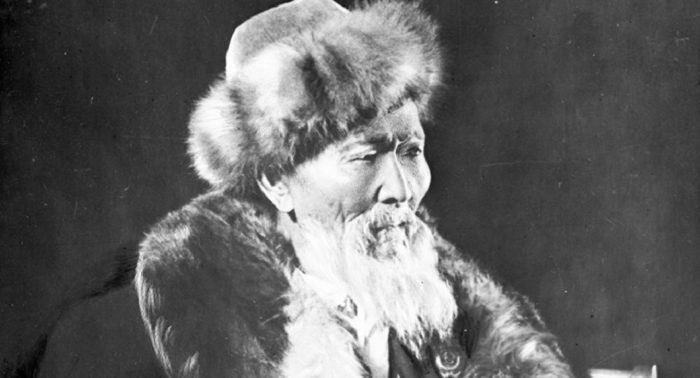

Zhambyl Zhabayev. Photo credit: Bilimdinews.kz.

Now we are celebrating his 175th birthday.

Zhambyl, who was born just four years after the death of Mikhail Lermontov and nine years after the death of Alexander Pushkin – the two great Russian poets. To feel the distance, it is enough to say that their images were brought to us only by painters – photography did not exist at the time of their early deaths in bloody duels. Zhambyl breathed the same air with them…

But Zhambyl is also the indispensable memory of our fathers’ childhood, the evergreen “grandfatherly figure”, who seemed so close, so “one of us” not only thanks to numerous photos in newspapers. But most of all – thanks to his beautiful, but also easily understandable verses about Kazakhstan, its nature, its people. But not only about the motherland – singing from Kazakhstan’s heartland, Zhambyl found a way to respond to the tragedy of World War II, Leningrad’s blockade, and many, many other tectonic “shifts of history” that took place in his lifetime.

The living room of the Zhambyl Zhabayev’s museum, which is located 70 km from Almaty where the poet lived in 1938-1945. Photo credit: Yvision.kz.

Could someone link these two worlds – Kazakhstan before its “Tsarist period”, the times of Pushkin and Lermontov, – and our generation, which saw the end of the Soviet Union and the success of independent Kazakhstan?

There is only one such figure – Zhambyl.

It is amazing that his world fame came to him around 1936, at the moment when he was 90. “You are never too old to learn” – this is a reassuring statement. But “you are never too old for fame” is an even more reassuring one. Zhambyl got famous in 1936, when a Kazakh poet Abdilda Tazhibayev proposed Zhambyl for the position of the “wise old man“ of the Soviet Union (aksakal), a niche traditionally filled by the ageing poets from the Caucasus lands. Zhambyl immediately won the contest: he was not only older (his competitor from Dagestan, Suleiman Stalski, was 23 years younger), Zhambyl was certainly more colorful. Raised near the old town of Taraz (later renamed after Zhambyl), Zhambyl had been playing dombura since the age of 14 and winning local poetic contests (aitys) since 1881. Zhambyl wore traditional Kazakh clothes and preferred to stick to the traditional protein-rich diet of the steppes, which allowed him live so long. But there was certainly something more to him – Zhambyl indeed was a poet.

A monument to Zhambyl Zhabayev in Almaty.

Critics (and some detractors) accuse Zhambyl of writing “political poetry,” of being blinded by the might (which was not always right) of the Soviet Union. There is some factual truth to that statement, but there is no aesthetic truth to it. Leopold Senghor, the legendary first president of independent Senegal, also wrote political verses, some of them about the “strength” and “might” of political “strongmen” of the 20th century. But Senghor wrote these verses sincerely – and he stayed in the history of literature. And Senghor stayed in history in a much more honorary position than the political strongmen, whom he admired.

For Zhambyl, the people of Leningrad, (now St.Petersburg) who sustained awful famine during the siege of their city by the Nazis in 1941-1944, – they were INDEED his children. In his verses, Zhambyl felt pain for every one of more than 1 million people starved to death in that majestic imperial city on the shores of the Baltic sea, whose palaces and bridges were so far away from him. For poetry, distances do not matter. It is the emotion that counts. And Zhambyl had a strong emotion. You can feel it reading his verses of a 95 years old man:

Leningraders, children of mine!

For you – apples, sweet as best wine,

For you – horses of the best breeds,

For your, fighters, most dire needs…

(Kazakhstan was famous for its apples and horse-breeding traditions.)

Leningraders, my love and pride!

Let my glance through mountains glide,

In the snow of rocky ridges

I can see your columns and bridges,

In the sound of spring torrent,

I can feel your pain, your torment…

(Verses translated by Dmitry Babich)

The famous Russian poet Boris Pasternak (1891-1960), whom Zhambyl could call a younger colleague, had huge respect for the kind of folk poetry that Zhambyl represented, wrote about this verses that “a poet can see events before they happen” and poetry reflects a “human condition” at its symbolic core.

This is certainly true of Zhambyl. His long life and work are a tale of human condition.