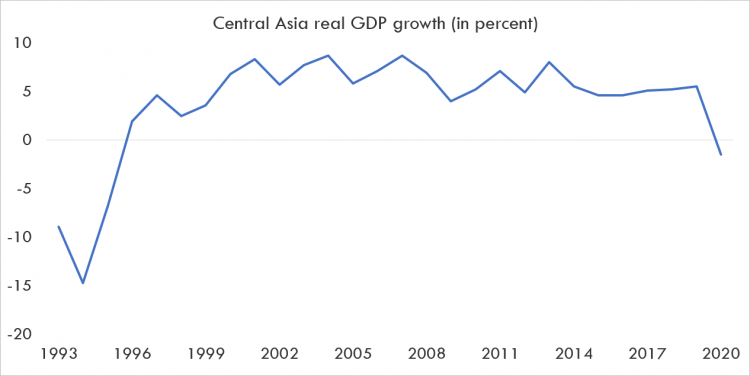

The Central Asia region is experiencing an economic contraction not seen for a very long time. Not since 1995, when the recession brought about by the transition from the soviet system ended. Not even during the Russian financial crisis of 1998, when global financial markets crumbled, and oil prices fell to single digits. Not during the 2008 global financial crisis, which affected countries around the world for more than a decade. And not during the sharp decline of oil prices in 2014-15.

Not until the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

For the Central Asia region, which is so commodity and remittance dependent, economic output will likely contract by 1.5 percent in 2020, according to the latest Economic Update for Europe and Central Asia.

Lilia Burunciuc

Three main forces are driving the contraction of the economy this year.

First, the measures governments in the region undertook to save lives by closing borders and limiting mobility and economic activity. Targeted fiscal measures in support of households and businesses only helped partially soften the pandemic-induced blow. And even though most lockdown restrictions in the region were lifted by September, activity is still depressed.

In Kazakhstan, retail and recreation activity is still down about a third from its early January 2020 levels and retail trade is down almost 12 percent. In Tajikistan, workplace mobility is down 24 percent.

Second, the sharp weakening of regional and global demand negatively affected exports. During the global financial crisis in 2008-09, China, an important trading partner for Central Asia, grew by 9.5 percent a year. In 2020, China’s economy is likely to expand by less than 1 percent.

Ivailo Izvorski

Add to this negative impetus the contraction in the Eurozone and in Russia, and it is no surprise that exports from the Kyrgyz Republic and Uzbekistan were down 22 percent year-on-year in January-July.

Reduced global commodity demand and lower commodity prices have similarly depressed exports from a region where shipments abroad of petroleum, natural gas, gold and other metals account for more than two-thirds of exports. In Kazakhstan, production at the giant Tengiz oil field fell 12 percent in the second quarter as the country adhered to the OPEC+ production cuts.

Third, remittances fell – albeit not as deeply as feared a few months ago. In the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan, two of the most remittance-dependent countries in the world, remittances were down 12 percent from a year earlier in January-August. In March and April, policymakers were worried remittances may contract as much as 40-50 percent.

That this did not happen reflects in part the limited containment measures in Russia’s construction industry, where a lot of the migrants work. But, in part, it is also due to an effort by migrants to provide a more sizable lifeline to their families back home, a phenomenon observed in other large remittance recipient countries.

Lower remittances, together with reduced domestic earnings, are hitting households hard and resulting in increases in poverty after two decades of progress. The World Bank estimates that, as a result of the economic shocks in 2020, an additional 1.4-1.9 million people in Central Asia will fall under the $3.2 per day poverty line used to estimate poverty in lower middle-income countries. Central Asia will account for nearly 60 percent of the new poor in the entire Europe and Central Asia region.

In 2021, growth in Central Asia is likely to rebound to between 2.7 and 3.7 percent, reflecting a recovery in demand abroad, including for commodities, higher commodity prices, and increased foreign direct investment. Uncertainty about the pandemic and a potential vaccine are the main risks to the 2021 outlook.

Beyond the near-term outlook, two main factors will determine the region’s progress going forward. First is the environment for vibrant private enterprise and the ability of governments to level the playing field, which is often tilted in favor of enterprises owned by or connected to the state or the elite.

Public investment has a large role to play in improving the conditions for dynamic private sector-led growth: from higher and greener investment in Kazakhstan, to more transparent and efficient investment in Tajikistan and Kyrgyz Republic.

The second factor is human capital, the most important asset for any economy. The recently released World Bank Human Capital Index for 2020, based on pre-COVID-19 data, indicated that a child born in Central Asia today is likely to achieve only 50-63 percent of their potential human capital; the range covers all countries in Central Asia.

These numbers are lower than the average for the entire Europe and Central Asia region – and they have declined over the last decade. More importantly, these developments are likely to be reinforced by the learning losses as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

A sustainable and resilient recovery from the crisis will ultimately depend on whether authorities across the region manage to transform education and health systems to more than compensate for the learning and health losses, and create an environment for the private sector to grow. With such policies, Central Asia can fully recover from the worst economic contraction in a quarter century.

The authors are Lilia Burunciuc, Regional Director for the World Bank in Central Asia and Ivailo Izvorski, Practice Manager in the Macroeconomics and Fiscal Management Global Practice of the World Bank.