Approximately 200 million years ago, the deserted steppe of the Mangystau Region was once the bottom of the ancient Tethys Ocean – a habitat for ancient marine organisms. Some locals seeking adventure sometimes go after prehistoric treasures for fun, but rarely find anything. For civil engineer Vladimir Yartsev such a hobby became an important part of his life.

Amature Paleontologist Vladimir Yartsev in Bozzhyra gorge on the Mangystau Region’s Ustyurt Plateau (Click to view on the map). Photo credit: Vladimir Yartsev’s personal archive.

Yartsev started his paleontological hobby three years ago, when he began working in one month shifts. He began by studying the relevant literature in paleontology and old maps. As of today, the amature poleontologist found a large quantity of bones, fins and teeth of extinct reptiles and fish, and the shells of ammonites (ancient molluscs) dating back hundreds of millions of years.

One of the most valuable of his discoveries were the bones of a large nine meter long ichthyosaur marine reptile, which he discovered in the village of Shetpe on the Mangyshlak peninsula on May 25, 2019. He passed it to the Aktau Museum of Local History as he “could never keep the finding. Because it is of such a high level of importance and value to our nation.”

A group from the Aktau Museum of Local History and Russian paleontologist during the ichthyosaurus excavation in May 2019. Photo credit: Vladimir Yartsev instagram page.

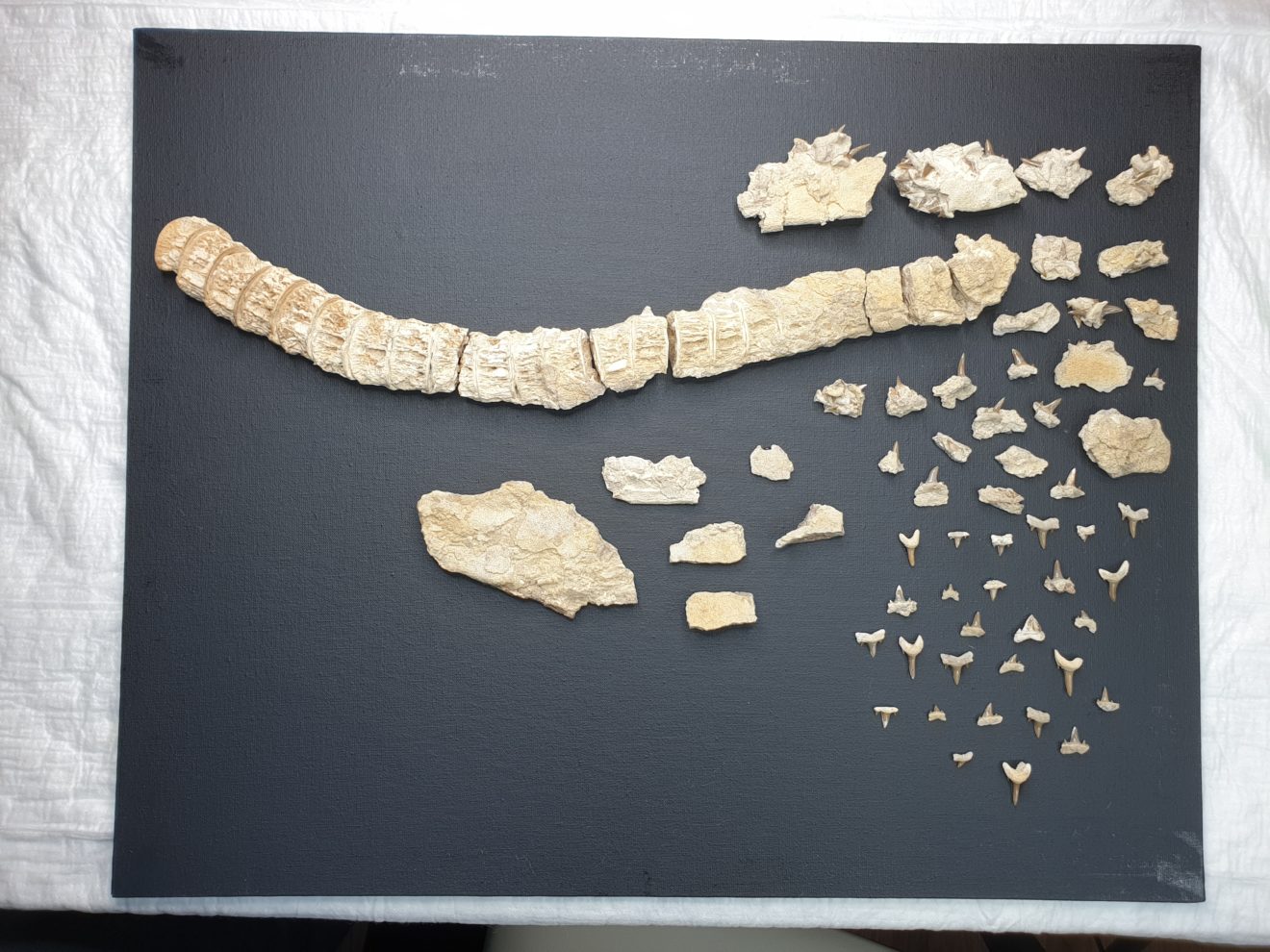

The paleontology enthusiast keeps a personal collection of fossils. Yartsev especially values his fragmented skeleton of a paleogene shark, which is approximately 40 million years old. To the surprise of many paleontologists, this specimen has preserved some flesh of the ancient shark’s jaw that has not decomposed.

“Almost the entire set of teeth, around 300 are preserved… but the real uniqueness of the specimen is the fossilized skin that remains on the fragments of the jaw. In general, soft tissues cannot be preserved or fossilized. But this finding proved this conventional wisdom to be wrong by demonstrating that not only such things as bones, cartilage, teeth, can be fossilized,” Yartsev told The Astana Time in an interview for this story.

Vladimir Yartsev’s most valued fossils – fragmented skeleton of a paleogene shark with peaces of intact skin. P hoto credit: Vladimir Yartsev’s personal archive.

According to Yartsev, scientists believed that they could find and recreate skin or fish scales as it often imprinted on surfaces, but could never find such a delicate sample such as skin on a fossil. This skin sample, therefore, raised the interest of several British private museums. The scientists and collectors were persistently asking Yartsev to send it to them for studies or made offers to buy it. The amature paleontologist, however, refuses all of such offers because he wants to open his own museum in Aktau.

“If it leaves my possession, it may never come back,” he said. “I plan to open a museum in the future. I would like to place all of my finds in a mini-museum. I’d like to revive paleontology, which has become an ‘extinct’ science in Kazakhstan.”

Vladimir Yartsev’s ammonites collection found in Sulukapa and Bozhyra gorge. Photo credit: Vladimir Yartsev instagram page.

The collapse of the Soviet Union started a crisis in the post Soviet space. Kazakhstan did not invest in fields such as paleontological studies, because they did not contribute to economic growth. Yartsev, however, wants to reinvigorate interest in paleontology with his museum project and revive the prestige of the old science in his country.

“As a child (in Soviet times), I remember my parents would always take me to see paleontological and geological museums in Almaty. I have always been interested in paleontological exhibits. But they have been taken down,” he said.

Yartsev also finds it easy to identify fossils because “all of the hard work categorizing them has already been done back in Soviet times by professional paleontologists… Everything has a classification and an approximate estimated age with an error of two to three million years.”

Yartsev shares all of his findings on his instagram page @hedgehog_1979, where foreign scientists and amature paleontologists and enthusiasts like himself work together to identify the age and characteristics of the fossil.