ALMATY – Learning losses from COVID-19 pandemic-related school closures will be felt for decades to come. This is the forecast of the experts who took part in the discussion of COVID-19 implications for education at the Education Transformation in Central Asia roundtable in Almaty on May 6.

The roundtable discussed post-pandemic recovery and educational achievements and challenges faced by the region of Central Asia. Photo credit: World Bank

Harry Patrinos, the Practice Manager for Europe and Central Asia Region of the World Bank’s Education Global Practice presented the grim figures at the roundtable.

Close to 90 percent of educational institutions worldwide were closed in 2020—2021 during lockdowns, and 1.65 billion students were affected. How will this impact their future and the future of their countries?

“Every additional year of education results in the growth of earnings of at least 8—10 percent, therefore, we expect a loss in personal incomes, and countries will also lose productivity and income,” said Patrinos. “The impact of the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918—1920 was felt as late as the 1980s. Several generations were affected, including the children who were at the time in their mothers’ wombs during the epidemic.”

Harry Anthony Patrinos specializes in all areas of education, especially school-based management, demand-side financing and public-private partnerships. Photo credit: World Bank

The longer the school closures during the pandemic, the more severe were the learning losses. This was the conclusion of the first studies conducted between March 2020 and March 2021, mainly in Western Europe. In Belgium, where the schools were closed for 30 weeks, students lost a whole year in learning outcomes in reading and mathematics, whereas in the Netherlands, where the lockdown was shorter, learning losses were half as big as in Belgium. In Europe as a whole, the students lost one-third of a year of learning on average.

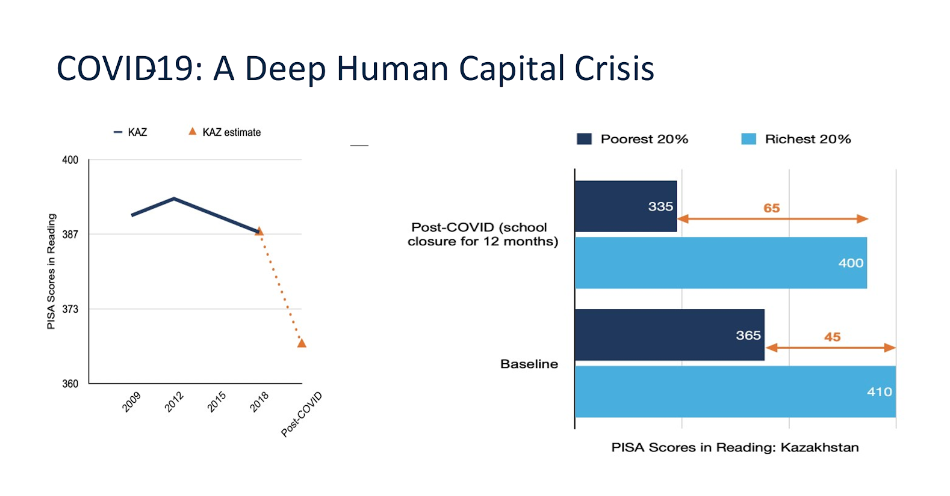

“These losses are not distributed uniformly. The worst affected students belong to the high-risk groups—the students who had fallen behind and children from low-income families,” stressed Patrinos. “If these learning gaps are not filled by grade 10, the students will be set back by one whole year.”

The reason for learning losses was a lack of preparedness for the transition to online education.

“Some countries tried to continue teaching via the radio, TV or even by sending assignments though the mail,” said Patrinos. But one cannot ask the TV a question—so, the interactive element was lost. Many countries faced limited capacity: many connectivity issues, power outages, not to mention internet and device availability. Some countries lost the gains made over the past decade. In the end, the students just stopped attending such classes: some would log in but would not participate. As a result, they forgot what they knew and missed the opportunities to learn new things.”

A series of 36 studies in 20 countries has concluded that during the second COVID-19 wave some countries managed to avoid learning losses. For instance, in Denmark, the government proactively provided learning resources to parents and cut down on the number of subjects. By focusing on foundational reading skills, they not only avoided learning losses, but also improved the skill levels of the students who had fallen behind.

“School closures and associated learning losses will lead to an annual GDP reduction of 0.8 percent resulting in a cumulative GDP loss of 12 to 18 percent over the lifetime of a generation,” said the World Bank representative. “Countries of the world will lose up to US$17 billion in students’ future incomes. Elementary students will sustain smaller losses (US$7,000 on average) than high school and university students (up to US$18,000).”

Apart from material losses, students’ mental health has worsened, and gender gap has widened: women are forced to leave the labor market.

According to Patrinos, human capital in Central Asian countries had stagnated before the pandemic. In Kazakhstan, the Human Capital Index was estimated at 63% in 2020, which means that a child born before the pandemic could expect to fulfill only 63% of his/her potential by the age of 18.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Kazakhstan already experienced a deep human capital crisis. Especially concerning were the gaps between socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged students (graph on the right). Slide from the presentation by Harry Patrinos, World Bank.

So, what needs to be done in order to offset the effects of the two-year-long coronavirus crisis?

First of all, World Bank analysts recommend regular educational assessments and monitoring access to education. This will enable educators to identify gaps and make remedial learning plans. Second, strengthened curriculum with a focus on foundational skills that form the basis for all future learning—reading and mathematics. Third, more effective teaching. This means, adequately funded and equipped training programs and courses for teachers. Fourth, additional learning time: remedial classes, shortened vacations, after-school programs, tutoring, including online. Fifth, providing socio-psychological help for students.

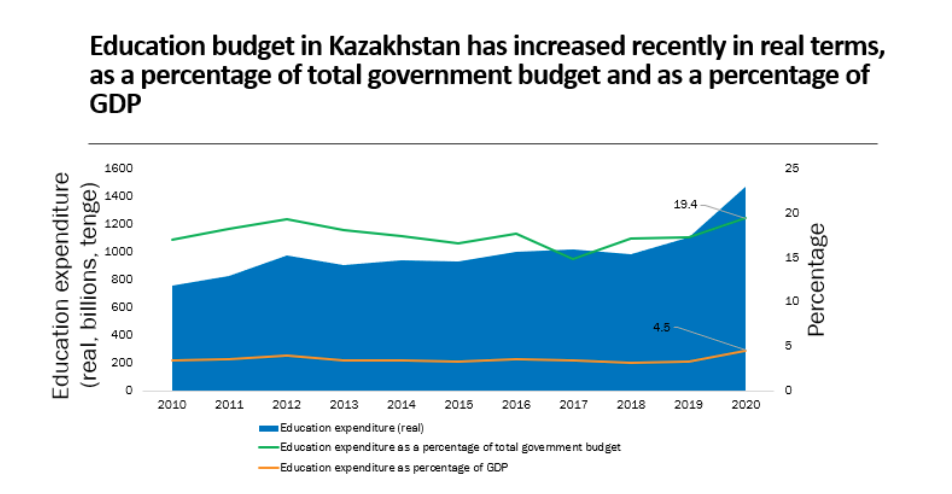

Practically all these policies require an increase in education spending in the budget, and the World Bank calls on governments to follow these recommendations. In Kazakhstan, before the coronavirus pandemic, the education budget was rising. But the spending was growing from a level much lower than what a country with an income level like Kazakhstan should have had. The speaker noted, however, that what is important is that money is well spent and on the most pertinent aspects: teachers, professional development, information systems, and assessment.

Closing his speech, the World Bank representative said that unfortunately, COVID-19 is not the last pandemic, and we must be prepared for future shocks.