The Global Climate Leaders’ Summit, held on 22 April 21 at the initiative of US President Joe Biden, clearly demonstrated the readiness of the countries of the world to cooperate in countering the climate threat. According to the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates, simply reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions will not be enough to keep global warming down to 1.5 ° C and prevent a climate catastrophe on Earth.

Commitments undertaken by Kazakhstan to achieve zero carbon dioxide emissions by 2060, announced by Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev in December 2020 at the UN Summit, demand immediate action on the structural technological restructuring of the economy and improvement of the carbon regulation as the first step to decarbonization.

One of the global trends in the development of the world economy at present is the search for ways of energy transition within the framework of the Paris Climate Agreement (PCC) from the use of traditional fuels to alternative energy sources. The implementation of the goal declared in the PCS – preventing an increase in the temperature threshold above 2 ° C – requires a complete rejection of the use of hydrocarbons and traditional technologies that cause significant emissions of carbon dioxide, deep decarbonization.

In this regard, the governments of 197 countries that have signed the PCS have begun to develop, and a number of countries in Europe and Asia have already adopted at the legislative level, national climate policy strategies aimed at achieving carbon neutrality till 2050-2060. The main focus of its achievement is the transition to a low-carbon path of development: more than 110 countries have pledged to move to carbon neutrality in the middle of this century. Leading multinational corporations such as Apple, Total, Bosch, BP and others have supported this global transition by announcing the decarbonisation and transformation of manufacturing structures.

This is evidence that a technological ‘revolution’ is taking place in the world economy, associated with new economic priorities, changes in the structure of the economy, and the introduction of market mechanisms for carbon development. According to the experts, “in the coming decades, low-carbon, based on reducing the negative impact on the climate and increasing energy efficiency, will become a key characteristic of advanced economies, since many of the world’s economies will have a new innovative and technological basis.”

Kazakhstan also joined this global process by signing and ratifying the PCC in 2015 and announcing its intention to achieve carbon neutrality till 2060 at the UN Climate Ambitions Summit in December 2020. At the same time, the achievement of the stated goals necessitates a radical modernization of the technological structure of the national economy and the adoption of more decisive and systemic measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs), especially in basic industries.

The need to take these measures is dictated by technological and environmental risks, the solution of which does not require delay: according to the latest data, our country is among the thirty polluting countries in the global ranking. According to The Global Carbon Atlas, Kazakhstan’s contribution to global carbon dioxide emissions at the end of 2019 amounted to 314 megatons of CO2, which makes the country 21st among 221 countries.

As you know, in the world there are various forms and methods of regulating GHG emissions.

In the economic regulation of GHG emissions based on the idea of a carbon price, two main mechanisms are applied:

– Taxes on GHG emissions (carbon tax);

– Emissions quotas (carbon caps).

Often these two mechanisms are complemented by emissions trading mechanisms:

– Taxes and trade (tax & trade);

– Quotas and trade (cap TM).

At the beginning of 2021, regulation of GHG emissions based on the principle of chargeable emissions is already applied in 64 countries and subnational entities (cities, provinces, states), which together account for more than 60 percent of GHG emissions. Of these, 29 countries and subnational entities have introduced a carbon tax, and 35 countries and cities have introduced ETS and other regulatory mechanisms.

Carbon taxes and an emissions trading system (ETS) have many similarities:

1) set a price for carbon, providing a direct financial incentive to reduce emissions;

2) require issuers to pay for emissions and reduce emissions, in the case of ETS with auctioned quotas.

The GHG emissions trading system is widely known throughout the world. The largest GHG trading in the world is considered to be the European Union ETS quota and emissions trading system (EU ETS). It includes 27 EU countries + Iceland, Norway, Liechtenstein, which are not EU members. Since 2009, the United States has had a regional quota and GHG emissions trading scheme to regulate CO2 emissions from the electricity sector. It involves the states of Vermont, Virginia, Delaware, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maine, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island. Since 2012, the California emissions trading and quota scheme has been launched, covering all sectors of the economy, including energy sourced from out-of-state. China, Germany and Russia announced the launch of national ETS at the beginning of this year.

Emissions / carbon / energy tax means that energy producers or owners of GHG emission sources pay a fixed fee (tax) for each ton of CO2 equivalent emitted into the atmosphere. When a carbon tax is imposed, a price is set that should be equal to the marginal cost of a given amount of emission reductions. The introduction of such a fee encourages the reduction of GHG emissions in response to the increasing rates of such taxes, to the adoption of less costly measures.

The carbon tax provides for 2 groups of taxes:

– tax on emissions (based on the amount of products produced);

– tax on services or goods, the production of which is accompanied by a large amount of greenhouse gas emissions (eg, gasoline).

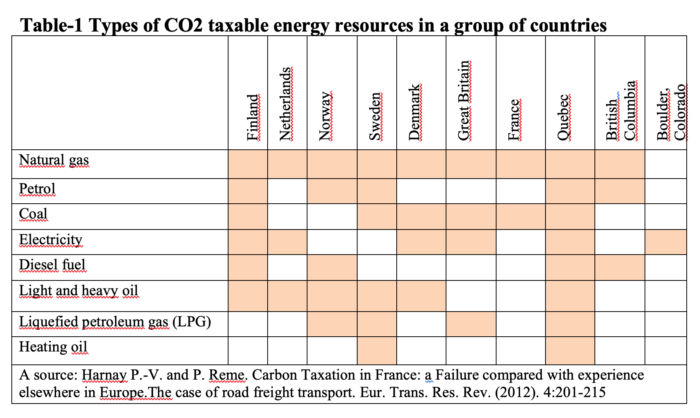

The history of carbon taxation begins with Finland, which introduced a tax on CO2 emissions in 1990. Then the Scandinavian countries adopted the practice of Finland: Sweden and Norway in 1991, Denmark in 1992. Poland introduced emission regulation mechanisms in 1993, Latvia in 1995, Austria, the Netherlands in 1996 (according to other sources, the Netherlands introduced a carbon / energy tax in 1990 in a 50/50 ratio), Germany and Italy – in 1999, Estonia – in 2000, Great Britain – in 2001. Since 2008, countries in Europe and the world have actively begun to introduce taxes on carbon emissions. This was due to the entry into force of the European system of quotas on carbon dioxide emissions (EU ETS) in 2005.

Experience has shown that countries and subnational entities around the world are most likely to tax goods and processes that emit greenhouse gases. Some of these taxes are general taxes that apply to all goods or activities (such as value added taxes or corporate taxes), while others apply specifically to carbon-intensive products (such as excise taxes on fossil fuels). According to research by the World Bank, carbon tax is levied: in Denmark, France, Japan, Sweden, Great Britain and a number of other countries, all types of fuel, in India – coal, in Norway – oil and gas. The most common sector exceptions are agriculture and international transport, both air and sea. In Australia, Chile, South Africa, electricity generation, large boilers and turbines, combustion of fossil fuels, and a number of industrial processes or goods are taxed. The cost of a carbon tax varies from country to country. Thus, according to the World Bank, the tax that is usually levied on a ton of CO2-equivalent emissions in 2015 ranged from $1 to $123, depending on the country and the type of fuel burned.

In the EU countries, the main tax payers are households – 44 percent (including personal transport) and industry – 37.9 percent (including electricity). The experience of European countries shows that other taxes, mainly excise taxes, dominate in the formation of the effective carbon tax rate, while the role of direct carbon taxes is still limited. Road transport has the most effective carbon tax, followed by electricity and industry, followed by buildings.

In the UK, the effective carbon tax rate for road transport is almost €280 / tCO2. In the industry of many countries, the average effective carbon tax rate exceeds €30 / t CO2 and is generated from energy taxes (in China, €10 / t CO2, in Sweden – €54 / t CO2). The more a country is dependent on fuel imports, the higher the carbon tax rate. Currently, countries are introducing energy taxation to reduce dependence on fuel imports.

Taxes specifically targeted to carbon-intensive products or processes have the effect of stimulating emission reductions and do not require an infrastructure for trade, making them relatively easy to administer. This aspect is less of a burden for the state than an ETS. At the same time, the introduction of a carbon tax presupposes a transformation of the tax system, taking into account the fact that maximum taxes should be imposed on nature exploiting and polluting activities (taxes on fuel and energy, on vehicles, depending on the volume of emissions, etc.), minimum – to high-tech and infrastructure sectors.

General conclusions on the priority of introducing a carbon tax are as follows:

– the carbon tax is easier to administer, it does not require the creation of infrastructure as for the emission trading system, and integration into the existing taxation system is possible;

– the possibility of monitoring, which is much easier, since the tax is collected at the place of energy supply;

– tax rates can be limited with a subsequent increase schedule, giving the business the opportunity and time to adapt;

– targeted use of proceeds.

At the same time, the carbon tax does not guarantee the achievement of the given volumes of GHG emissions. It is only effective when combined with other low-carbon development policies.

As you know, the European Council on July 21, 2020 decided to introduce a Carbon Boarder Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) from January 1, 2023. It is introduced with the aim of supporting European companies that switch to renewable energy sources and incur additional costs in this regard. The structure of this mechanism provides for an import duty on carbon-intensive imported goods. It is assumed that from 2023 , CBAM will cover ferrous metallurgy, the production of mineral products, and from 2025 – the chemical industry, all types of the metallurgical industry and petrochemicals.

The taxable base will be direct and indirect emissions of GHGs, which took place in the entire chain of added value, from the extraction of minerals to the production of this product. In general, the import supplier will be forced to pay the cost of carbon emissions at the price of EU GHG credits minus the paid carbon price in the country of origin. If the exporting country already has an ETS or has introduced a carbon tax, its value will be deducted from the CBAM, up to zero, if the prices for CO2 emissions of the two countries turn out to be comparable. CBAM is currently being negotiated with the WTO.

For Kazakhstan, the transition to a low-carbon development path will require a revision of approaches to state support for economic development, significant public and private investments in the coming years. The International Institute for Sustainable Development (UK) suggests that in order to achieve the ambitious goal of carbon neutrality and ensure financing for low-carbon development, it is necessary to accumulate additional funds, which is possible through the use of carbon pricing instruments such as an ETS and a carbon tax.

The introduction of a carbon tax as a minimum price for CO2 emissions, could be an addition to the existing system of trading in quotas for GHG emissions in Kazakhstan (ETS KZ). The introduction of a carbon tax in those sectors that are not covered by the ETS KZ will generate additional revenues for the budget, as well as provide a stable price signal for energy consumers and reduce emissions in the long term.

The ETS of Kazakhstan was launched in 2013 and it covers 225 large installations in the electricity, oil and gas sector, mining, metallurgical, chemical and processing (in terms of the production of building materials: cement, lime, gypsum and bricks) industry. Smaller installations in these sectors, as well as sources of emissions in agriculture and transport are not included due to the complexity of administration.

The policy in the field of reducing GHG emissions will be more effective if it is considered as an important component of the overall strategy of socio-economic development, which is fully consistent with the priorities of the UN SDGs and the Paris Climate Agreement(PCA).

Currently, the Ministry of Ecology, Geology and Natural Resources of Kazakhstan, with the support of GIZ, is working on the development of a draft Concept for low-carbon development of Kazakhstan until 2060.

We consider that the development of this strategic document should be accompanied by the development of an appropriate Action plan till 2060 and the creation of institutional mechanisms such as the Agency on climate under President of Kazakhstan for coordinating this process on the national and regional level. Besides, this process of decarbonisation of the national economy should be implement by the broad participation of international community, academia and business, as required of the new system of state planning and only this way will the transition to the trajectory of sustainable development be ensured.

The author is Bakhyt Yessekina, Director of the Green Academy Scientific and Educational Center, Doctor of Economics, Professor.