ASTANA — The Eurasian Development Bank (EDB) report on Cooperation of Multilateral Development Banks in Developing Countries: New Opportunities lands squarely in the middle of a growing global contradiction: developing economies face an unprecedented demand for financing, yet multilateral development banks (MDBs) remain structurally constrained in how much and how effectively they can deliver on their own. The report, released on Jan. 22, notes that the answer is not simply more capital, but smarter coordination. In short, MDBs need to stop working in parallel and start working together systematically.

Photo credit: Shutterstock

A $4 trillion question

According to multiple estimates cited in the report, achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals requires approximately $4 trillion in annual financing. MDBs, despite their growing role, cover only a fraction of that need. Central Asia is a case in point. As EDB Chairman Nikolai Podguzov puts it, global development banks tend to shape strategic vision, while subregional banks provide granular knowledge of local realities. Central Asia demonstrates how powerful and underused that combination can be.

The region faces an annual investment gap of more than $50 billion, while the combined annual financing provided by multilateral development banks has averaged around $10 billion over the past five years. We must help close this gap by increasing capital and strengthening cooperation among MDBs,” Podguzov said.

According to the EDB, that mismatch is not a rounding error; it is structural. To close this gap will require a shift away from institution-by-institution expansion toward a model built on coordinated action.

From parallel efforts to shared balance sheets

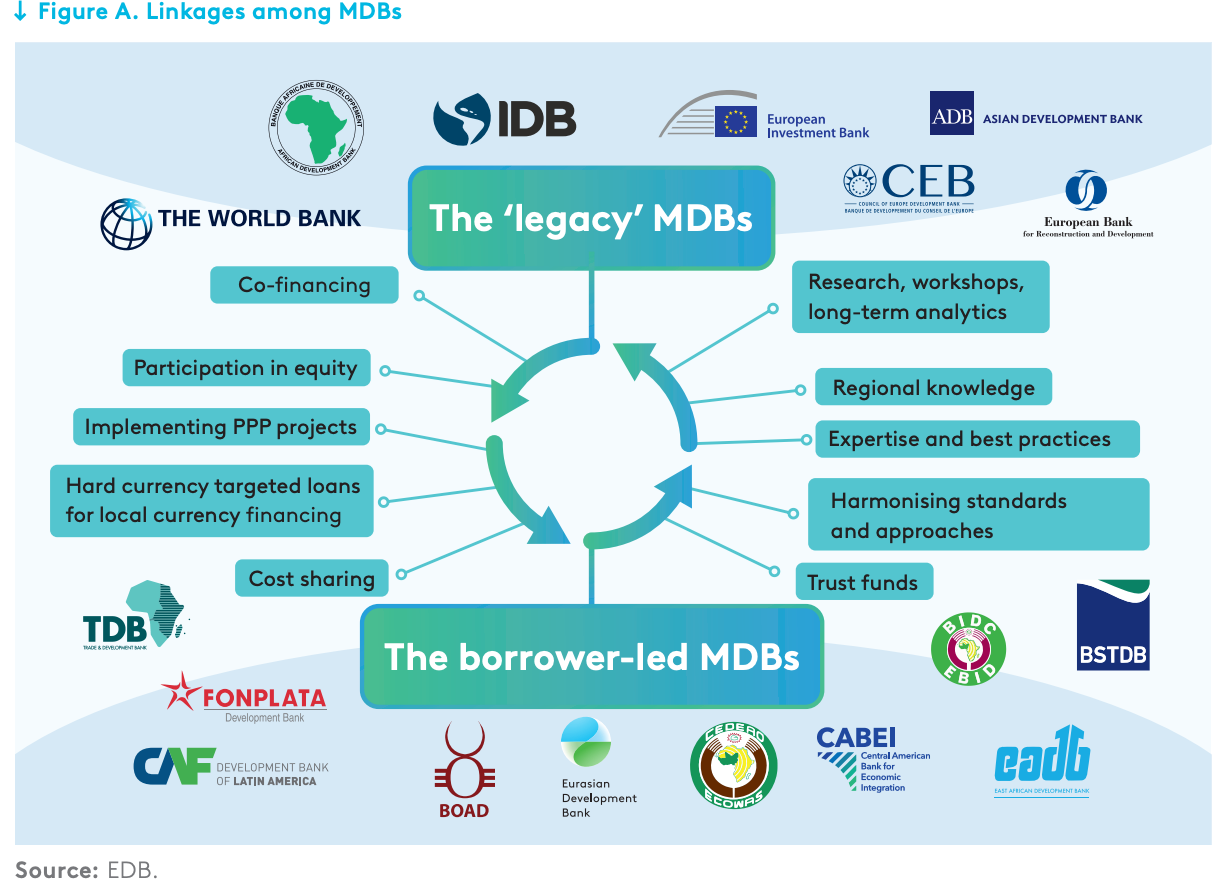

The report highlights a core limitation of the current system: individual MDBs often cannot finance large-scale infrastructure projects on their own. Capital adequacy rules, exposure limits, diversification requirements, and long project tenors frequently exceed the capacity of a single institution. Joint financing arrangements allow MDBs to overcome these constraints by sharing risks and exposures.

Instruments such as exposure exchange agreements, already used among global development banks, demonstrate how balance sheets can be extended without undermining financial stability. Cooperation, in this sense, becomes a way to increase capacity without eroding prudential standards.

Capital-market cooperation represents another underused lever. Larger, higher-rated MDBs are better positioned to access international markets on favorable terms, while smaller regional institutions often face higher borrowing costs. Strategic equity participation or investments in MDB-issued bonds can improve financing conditions for smaller banks while strengthening regional capital markets. Climate finance and labeled instruments, including green, social, and sustainable bonds, further expand the scope for joint action as demand for such products grows.

Local currencies, lower risks

Local currency financing emerges as a critical theme in the report. Lending in national currencies protects borrowers from exchange-rate volatility, which has repeatedly amplified financial stress during periods of depreciation. While demand for local-currency loans is rising, not all MDBs have the capacity to provide them at scale. Cooperation allows larger institutions to supply hard-currency funding to smaller MDBs, which can then on-lend in local currencies while collectively managing risks. This approach improves resilience without shifting excessive currency risk onto borrowers or domestic financial systems.

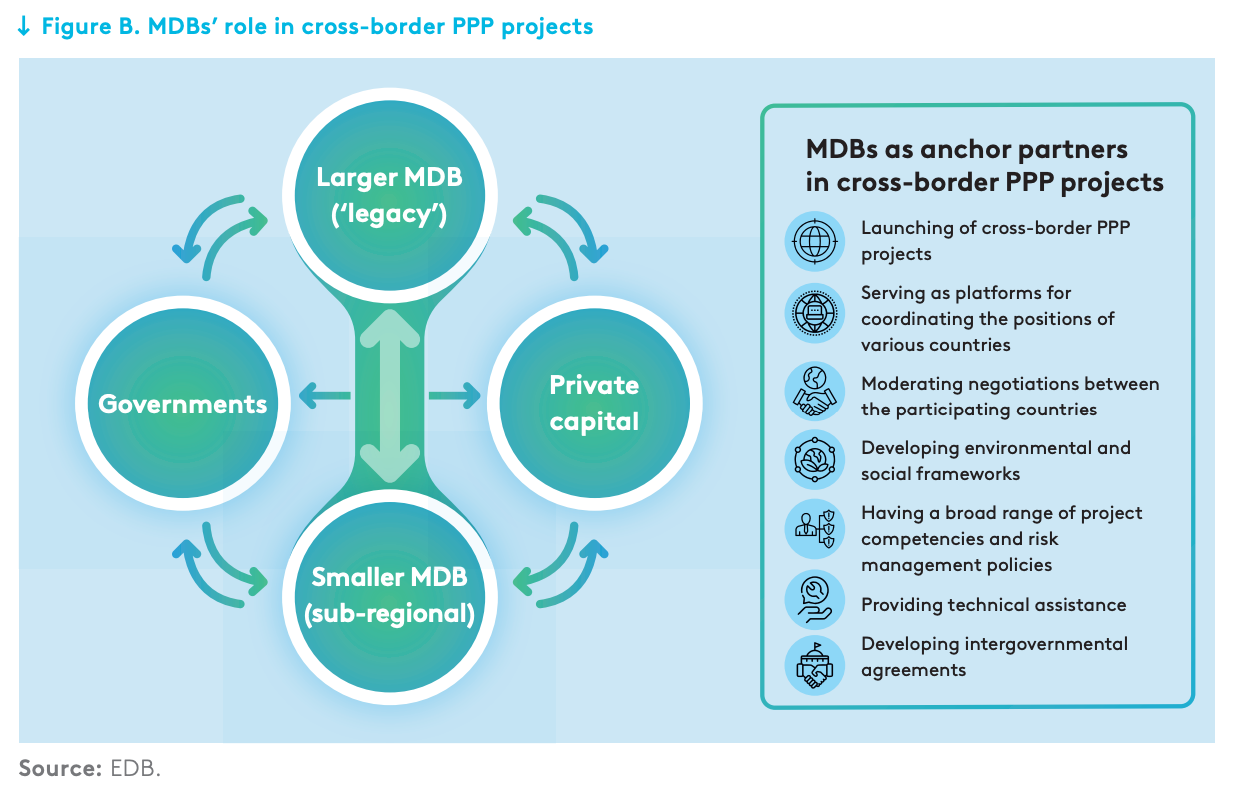

Beyond financial instruments, cooperation also reshapes how projects are designed and delivered. MDBs bring experience in structuring long-term investments, particularly public-private partnerships. Their established relationships with governments, risk-management frameworks, and specialized financial instruments often determine whether projects attract private capital or stall at the feasibility stage. Cross-regional cooperation enhances this role by facilitating knowledge transfer and sharing best practices across institutions.

Knowledge, not just capital

The report emphasizes that MDBs possess extensive analytical capacity rooted in country and regional experience. Yet much of this knowledge remains siloed. Joint research initiatives, shared databases, and coordinated training platforms reduce duplication and improve efficiency, particularly for cross-border projects where fragmented standards and inconsistent data frequently delay implementation.

Technical assistance is another area where joint action yields tangible benefits. Project preparation is resource-intensive, especially in emerging markets with limited institutional capacity. By pooling technical expertise and funding for feasibility studies, MDBs can improve project quality and build pipelines for future co-financed investments. In practice, technical cooperation often determines whether development strategies translate into executable projects.

Where cooperation delivers the highest impact

Based on case studies and international experience, the EDB identifies four sectors where MDB cooperation generates the greatest economic returns: the water–energy–food nexus, sustainable transport connectivity, climate and sustainable finance, and cross-border infrastructure.

In the water–energy–food nexus, MDBs can support regional consortia or project-based investment platforms using build–operate–transfer or build–own–operate–transfer models. As financial intermediaries, MDBs can arrange syndicated lending, mobilize donor funding, and host coordination bodies focused on sustainable resource management.

In transport, coordinated MDB action supports the development of economic corridors, improved border-crossing procedures, and low-carbon mobility solutions, thereby aligning national infrastructure projects into coherent regional systems rather than isolated investments.

Climate and sustainable finance also benefit from joint approaches, including syndicated loans, guarantees, technical assistance, and targeted issuance of green and sustainability-linked instruments. MDB cooperation helps reduce risks, improve standards, and support the growth of local green finance ecosystems.

Finally, cross-border infrastructure projects underscore the limits of unilateral action. These initiatives require coordinated planning, political alignment, and substantial resources. Acting together, MDBs can mitigate political risks, align national priorities, and serve as anchor investors that can crowd in private capital.

A structural shift

The EDB report avoids idealism. Cooperation among MDBs will not eliminate development constraints, but it can make them manageable. By pooling capital, expertise, and risk, MDBs can finance larger and more complex projects, accelerate implementation, and better adapt investments to the needs of emerging economies. For Central Asia, where infrastructure, climate adaptation, and connectivity demands are accelerating simultaneously, the cost of continued fragmentation is rising faster than the risks of cooperation. In today’s development landscape, MDB cooperation is no longer optional: it is the only scalable response to a widening investment gap.