ASTANA — Public spaces are undergoing a transformative shift. No longer just libraries or youth centers, these areas are evolving into vibrant, creative hubs that foster community, culture, and innovation, according to experts, who spoke to The Astana Times.

Public library in the cultural-sports complex in Kosshy. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

What is a public creative space?

Kamila Lukpanova, the founder of the Almaty Tourism Bureau and the TANA Foundation, which implements public space projects across Kazakhstan, sees this evolution as both timely and necessary. She draws on international experience to frame space as an interactive and social catalyst.

Kamila Lukpanova, the founder of the Almaty Tourism Bureau and the TANA Foundation. Photo credit: Lukpanova’s personal archives

“A public creative space is where people with diverse interests come together around a shared purpose. It boosts and encourages collaboration, sparks inspiration, and enables personal and collective development,” Lukpanova said.

She noted that while some people may view coffee shops, such as Starbucks, as informal and creative spaces, they are not accessible to everyone.

“That is why it is great that in Kazakhstan, these spaces are now becoming part of government programs, offering people free access and opportunities to use them,” Lukpanova said.

According to her, larger cities, such as Almaty, Astana, and Shymkent, have seen the earliest growth of such spaces, but regions are now catching up. Her team spearheaded a project that converted 25 rural libraries in the West Kazakhstan Region into multifunctional community hubs.

“In these villages, attendance doubled or tripled. People form queues to join hobby clubs, and even graduates return for photoshoots because the spaces are so aesthetically appealing,” she said.

Lukpanova emphasized that these initiatives are more than surface-level improvements.

“Why is it important to bring this to the regions as well? Because, even in Almaty, we have seen the positive impact of creating beautiful, creative spaces. Among other things, we are helping improve people’s taste, aesthetic sense and visual literacy,” Lukpanova said.

“People now recognize that this is their standard: ‘I have the right to have beauty around me. Beauty that is accessible and free.’ In the future, they will not be surprised by a stylish armchair or complimentary coffee. And that is part of our mission – to make this the norm,” she said.

Lukpanova also highlighted how libraries have evolved into community-centered spaces. When state programs support free entry, 24/7 access, and Wi-Fi, these institutions become creative platforms for growth and development.

“They [libraries] can definitely be considered cultural and creative public spaces because they have evolved into cultural hubs while preserving their core functions. Books, of course, remain the priority, and everything was designed around them. These spaces fall within that same concept,” she said.

Spaces that empower creators and citizens

Baurzhan Sagiyev, the director of the TSE Art Destination gallery, echoed the significance of accessible creative platforms. His team has organized exhibitions and festivals, such as the Astana Art Show, which attracted thousands of visitors.

Baurzhan Sagiyev, the director of the TSE Art Destination gallery. Photo credit: Sagiyev’s personal archives

“We have had openings where 1,500 to 2,000 people came to a small gallery. The demand is there. We have seen it empirically,” he said.

While professionals understand the value of such spaces, public awareness is still evolving.

“Take Barbican in London as an example. Everything there is free. There is a library, public areas, cafes and art galleries. Only cinemas and theaters charge entry. Barbican was originally built for residents, but it has become a public space for the entire city. It is managed by the mayor’s office. So not all such spaces need to be commercial. Many are often sponsored or supported by patrons and philanthropists,” he said.

Sagiyev noted that in Kazakhstan, the state remains the primary supporter of such spaces.

“Private creative institutions are rare and typically short-lived without ongoing funding or administrative support,” he added.

He also highlighted the long-term social impact of such environments.

“Cultural infrastructure influences the surrounding area. According to the broken-windows theory and recent studies, even small art spaces can reduce crime and social issues. They shape safer, more cohesive communities,” he said.

Global concepts, local adaptation

When asked about repurposing old buildings into cultural spaces, a trend seen in cities such as New York and Moscow, Sagiyev recalled Kazakhstan’s early experiments.

“Such initiatives began in the late 1980s, like in New York’s SoHo district. It later became a trend. In Moscow, there’s Winzavod, Flacon, Strelka – all of them former industrial sites,” he said.

Otz Alt, also known as Dom 36. Photo credit: Daniil Devyatkin / kz.kursiv.media

“Here, we had an art residency in a former prison administration building in Almaty, and Dom 36 on Baitursynov Street. It was located in the former Embassy of Uzbekistan,” said Sagiyev.

Yet these efforts often faltered due to a lack of sustainable funding. “These projects need ongoing management. Without state or patron support, they don’t last,” he said.

Why it matters: creativity as a catalyst for development

Sagiyev said that exposing children to creativity and the arts from an early age is essential for developing critical thinking, imagination, and problem-solving skills.

“I hear from parents that their kids are struggling with abstract thinking. But that is a crucial skill for IT and all modern professions,” he said.

He referenced global practices, such as Tate Gallery’s early school outreach programs in the United Kingdom, as powerful models. According to Sagiyev, culture leaves a long-lasting imprint. The impact is not always immediate, but it is profound.

Modeling and sewing class in cultural-sports complex in Kosshy. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

“It has a strong impact on children, teenagers, and youth (…) With sports, the results are easier to see because children run and train. Culture has a less visible outcome, but it is there. The effect is long-term. It does not produce results right away, but its influence is powerful,” he said.

Sagiyev also drew on the broken windows theory, which suggests that areas with a high concentration of cultural institutions tend to experience lower crime rates and fewer social issues.

“Where there is a gallery or a museum, there is less crime, less aggression, fewer everyday problems. It has both social and practical effects,” Sagiyev said.

A case study: Kosshy’s cultural-sports complex

A vivid example of Kazakhstan’s community-driven approach is the cultural-sports complex in Kosshy, some 100 kilometers from Astana, which opened in April. It is an 8,500-square-meter cultural-sports complex that includes a library, cinema, lecture halls, studios for robotics and culinary arts and other types of classes.

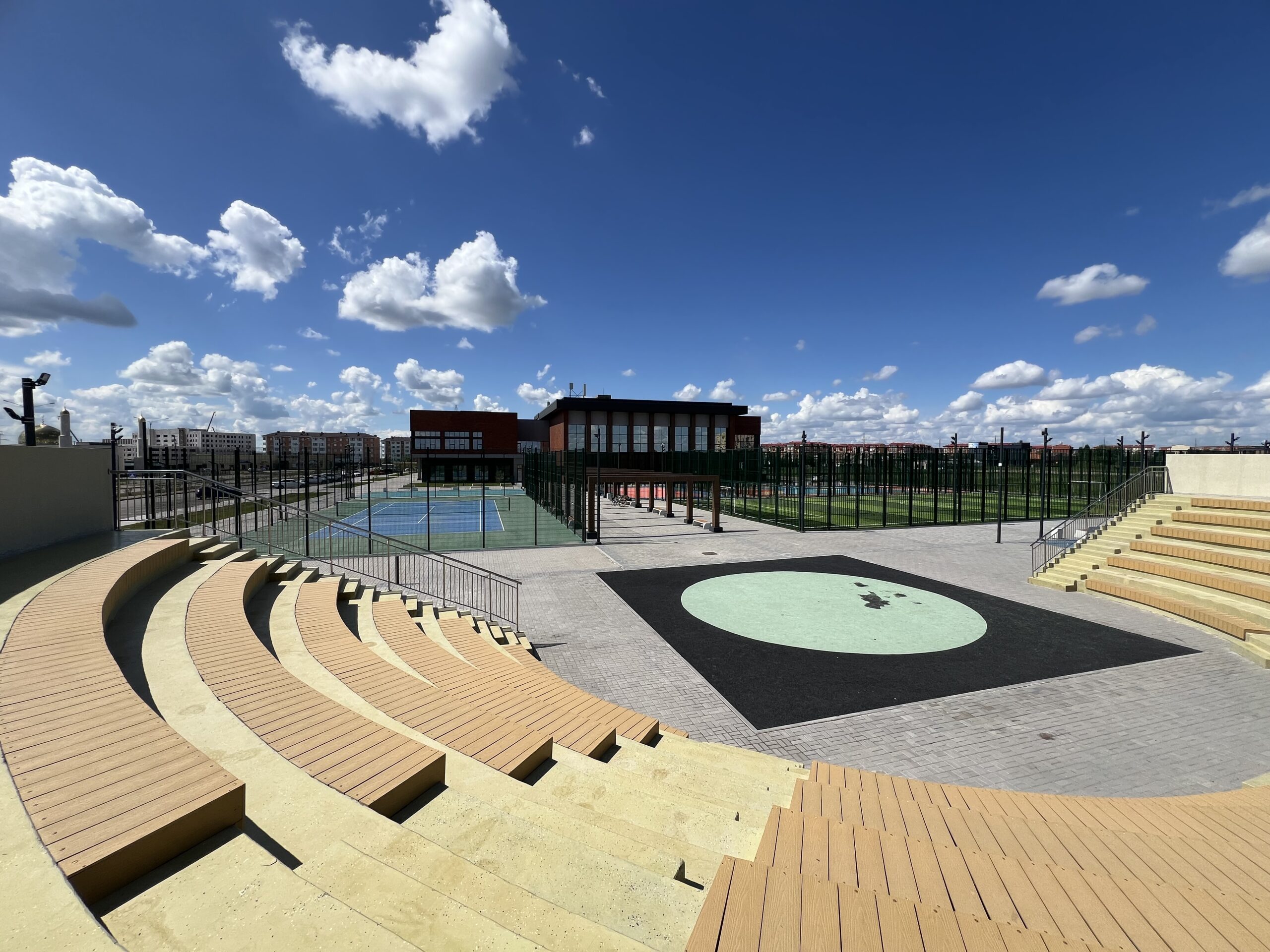

Sports center in Kosshy. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

With a focus on inclusivity, it offers free or affordable programs supported by municipal funds and ArtSport vouchers.

“We teach modeling and sewing to girls aged between eight and 15. They learn both hand-stitching and machine work. It is free for most kids through government programs. If parents want more than two courses, they can pay a small fee,” modelling design instructor Saule Isatayeva told The Astana Times.

Public library in the cultural-sports complex in Kosshy. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

The on-site library hosts more than 20,000 titles in Kazakh, Russian, and English, and staff noted a growing interest in business and self-development literature among youth.

Diana Gainulina. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

“We regularly host book clubs and collaborate with schools, clinics, and kindergartens. The reading culture is very much alive,” said librarian Saule Omarova.

Pottery teacher Diana Gainulina described the excitement of students working with clay and ceramics.

“We moved from a basement to this new bright space. Kids love it here – the atmosphere, the lighting, and the quality of the materials. When children use their imagination through sculpting, the space around them influences their mindset. Creating something in a beautiful environment feels completely different,” Gainulina said.

Similarly, robotics teacher Ayimgul Kosshybayeva highlighted the center’s academic impact.

“Our students recently took first place at a robotics competition in Antalya, among 50 teams,” she said.

A matter of will, not just resources

While modern facilities matter, Lukpanova emphasized the role of institutional will.

“Kazakhstan inherited a vast network of libraries, cultural houses, and postal branches from the Soviet era. They exist in nearly every village. Many are in poor condition, but the space is there,” she said.

She noted that the human resource pool is also strong.

Works of children of modeling and sewing class in Kosshy. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

“Many librarians and cultural workers are incredibly passionate. They are ready to upgrade their skills. We are training them to be community managers, not just custodians of books,” she said.

Ultimately, the experts highlighted that it is the intersection of policy, funding, community engagement, and vision that sustains creative public spaces.

“It is a long-term investment. Culture may not show results overnight, but it deeply shapes individuals and societies,” said Sagiyev.