ASTANA – Industrial policies are making a global comeback, but not without controversy. The latest Transition Report from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) warns that while their use may be justified to address clear market failures, their track record remains uneven. In an interview with The Astana Times, Beata Javorcik, EBRD’s chief economist, explains the drivers behind this surge, and some of its pitfalls.

Global comeback

Assel Satubaldina and Beata Javorcik during the interview in the EBRD office in Astana. Photo credit: The Astana Times

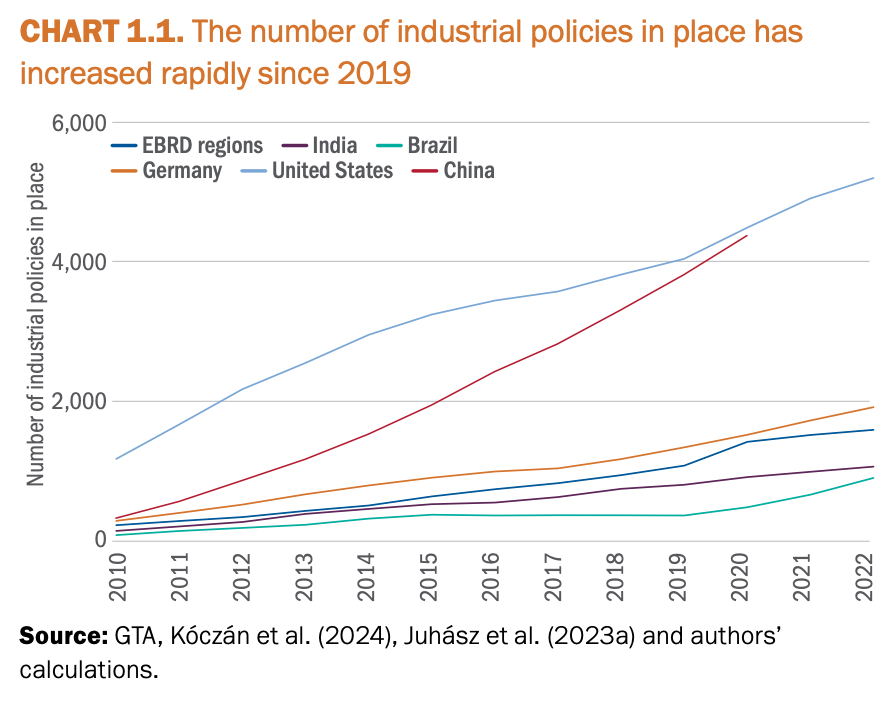

EBRD defines industrial policies as those “aimed at changing the sectoral composition of production in an economy.” Javorcik said industrial policies are not new, as they were used heavily in the 1970s-80s.

“By the 1990s, there was a feeling that industrial policies are not a solution and that governments are not good at picking winners. Now, we are seeing a renaissance of industrial policy, with countries, ranging from the U.S. and China to Brazil and India, introducing them quite enthusiastically,” said the chief economist.

Why are industrial policies on the rise?

According to Javorcik, there are several reasons behind the increased use of industrial policies.

“First, governments want to use them to boost the competitiveness of their economies and speed up the decarbonization process. Countries are doing industrial policy in response to what their competitors are doing. In Europe, industrial policy is high on the agenda in response to the U.S. inflation reduction act, which offers subsidies to green activities and in response to subsidies given by China to the producers,” she explained.

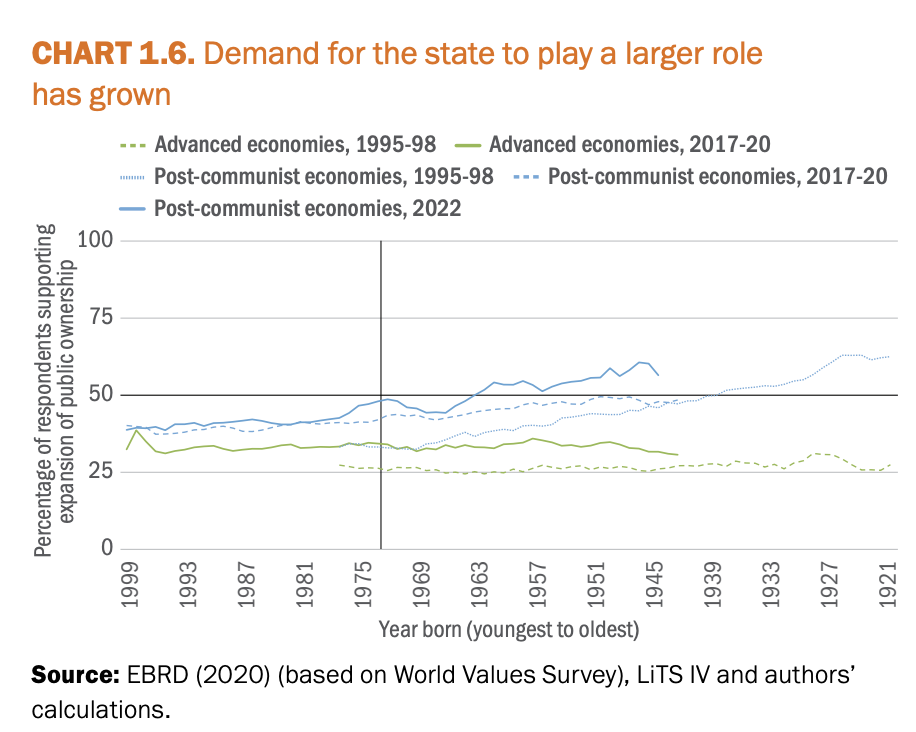

Javorcik also pointed out that across EBRD regions and beyond, the public is increasingly in favor of greater state involvement in the economy – from government intervention to expanded public sectors and generous subsidies.

Emerging pressures

This global resurgence doesn’t happen in a vacuum, according to the report. As major economies pursue strategic interventions, other countries are also following the move.

EBRD’s Transition Report notes a resurgence in the industrial policies globally, both across high-income and emerging economies. Photo credit: EBRD

The report warns that domestic political economy pressures, rising geopolitical tensions, and the actions of others are pushing policymakers away from optimal economic strategies and undermining international cooperation. This leads to distortionary outcomes, particularly in low-income countries that tend to have weaker institutions and limited fiscal space.

U.S. trade policies, for example, have ripple effects on economies worldwide. While Central Asia is not exposed much to these impacts, countries such as Slovak Republic or Hungary, are under a bigger risk, because they export cars and car parts to the U.S.

“In our report, we ask a question, how much would our countries of operations be affected if the U.S. increased its tariff by 10% on all imports from all over the world? And the answer is that the impact would be rather modest. That’s because relatively few of our countries are direct exporters to the U.S.,” she said.

The indirect effect, however, can be substantial, especially through the German economy, which is heavily intertwined with supply chains in Central and Eastern Europe.

“20% of German car exports are directed to the U.S. market. Actually, the U.S. is the largest market for the European Union, so tariffs on European exports to the U.S. could lead to a slowdown in the German economy, and this, in turn, would lower demand for exports from emerging Europe and emerging Asia,” she said.

Hard to do industrial policy right

While some countries perceive industrial policies as a “silver bullet” or a “quick fix,” Javorcik said they “express a healthy dose of skepticism,” in the report “pointing out that while industrial policy may be effective, it is actually hard to do it right.”

Governments often use the same policy tool to pursue multiple, and sometimes conflicting, objectives, which can undermine its impact. Another common pitfall is the absence of a clear sunset clause.

Popularity of industrial policy reflects public demand for a larger state. Photo credit: EBRD

Poorly designed industrial policies can undermine the wider economy, she added.

“What you mentioned is the creation of bottlenecks and the creation of effects for other sectors. For instance, often governments promote one sector, forgetting that their policy may be actually harmful to other sectors. For instance, tariffs protecting steel production helps steel producers, but hurt industries using steel as an input,” she said.

Javorcik emphasized that for effective industrial policies, two things are crucial – administrative capacity and funding.

“What we document in our report is that countries that don’t have funding or administrative capacity tend to go for simple and cheap policies. Unfortunately, these policies, which often involve restricting exports, restricting imports, licensing, are the type of policies that introduce distortions,” she explained.

In contrast, tools such as trade finance, incentives to boost local value addition, and local content requirements in public procurement typically require a higher degree of administrative capacity to implement effectively.

What good industrial policy looks like

If governments are ambitious to implement industrial policy, they should approach it with discipline and clarity.

“If you want to do industrial policy, articulate why you are doing this. Build in competitive pressures. If you think about the success of China’s electric vehicle industry, China did give subsidies to car producers. But there is very strong competition between various car producers, and that’s what made them so successful,” she said.

Industrial policies shouldn’t also be open-ended commitments. They should have an exact “expiry date.”

Because effective industrial policies depend on implementation, they should go hand in hand with reforms and sustained investment in administrative capacity and bureaucratic quality.

“Don’t forget the reforms that benefit everyone, such as improvements to the business climate,” she added.

For Javorcik, minimizing market distortions is key — and one of the most effective, low-risk tools is investment promotion.

“By investment promotion, I mean marketing a country, explaining that Kazakhstan is a great place to do business in this and this sector. It’s about contacting foreign investors, providing information they may need to make their decision. It’s about helping them navigate bureaucratic requirements once they decide to enter the country,” she explained.

What makes this particular policy stand out is that it carries less fiscal risk, unlike subsidies or tax breaks.

Good governance is key

Turning to Kazakhstan, Javorcik sees clear opportunities for governance improvements.

“For instance, governance of state-owned enterprises. Better governance, including better procurement roles, is something that can make state-owned enterprises more efficient,” she added.

Privatization is another priority.

“The EBRD is a proud owner of 5% of shares of Air Astana [Kazakhstan-based airline]. We participated in the IPO of the company, and we believe that privatization is something that boosts the competitiveness of the economy,” she said.

A third area of focus is public and private partnerships (PPPs). “We have been working with the government to improve the legislative framework for PPPs. We have actually participated in a PPP project to build a state-of-the-art hospital with more than 600 beds,” she added.

Stay tuned to The Astana Times YouTube channel for a full interview with Prof. Javorcik coming next week.