ASTANA – Kazakh scientist Nurzada Amangeldy is developing a project that will translate sign language into Kazakh using artificial intelligence (AI) in hopes of changing life for the hard-of-hearing community in Kazakhstan.

Photo credit: freepik. Collage is created by The Astana Times/ Fatima Kemelova.

Amangeldy was born in Mongolia. She moved to Kazakhstan with her family after the country gained independence. She is now carrying on her father’s dream of contributing to Kazakh society.

“In 1993, my father and his family moved to Kazakhstan. He is a graduate of the Abai Kazakh National Pedagogical University and a teacher. While living in Mongolia, he received a scholarship from Kazakhstan and completed his higher education here. His dream was to return to his homeland with his family and to serve it, and I think he has already fulfilled that dream,” said Amangeldy in an interview with Kazinform news agency.

Amangeldy’s scientific journey began in 2002, studying informatics at Pavlodar State University. Later, she transferred to Astana-based Gumilyov Eurasian National University. After earning her diploma, she pursued a master’s degree, and in 2019, she returned to Eurasian National University for a doctoral program focusing on AI.

AI-powered solutions for sign language

Her research at the Department of Artificial Intelligence Technologies at Gumilyov Eurasian National University focuses on improving social inclusion for people who are deaf or hard of hearing and those with speech disabilities. She is developing AI-powered solutions to translate sign language into Kazakh to enhance communication and accessibility within the broader community.

Photo credit: from the personal archive of Nurzada Amangeldy.

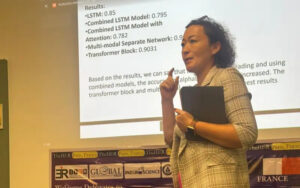

“I defended my doctoral thesis last year, but the research continues. We have been successful in allowing the speech of people who use sign language to be transcribed into text. We recognize hand movements and lip shapes and adapt electronic information into sign language,” said Amangeldy, sharing the research progress.

The Kazakh language has around 40,000 words, while sign language contains only 2,500 to 3,000. Although there are 120 official sign languages worldwide, Kazakh sign language has yet to be developed. Amangeldy expressed optimism about adapting sign language to the Kazakh language.

“There are no clear standards for Kazakh sign language yet, so I chose 1,000 words in Kazakh, Russian, English and Turkish and compared them. Of course, there are words that have no alternatives in other languages, such as ‘aksakal’ [elder] and ‘baybishe’ [wife of the elder], which we adapted for Kazakh sign language. Based on this work, I published a scientific article with the conclusion that sign language can be translated into Kazakh, and I am continuing research based on this material,” she said.

A project that supports social inclusion

Amangeldy conducted an experiment by translating 4,000 words into Kazakh sign language.

“Only 400 of them are commonly understood, which means that if I read two pages of text, they would understand only 20%. Our goal is to adapt the information and improve literacy because a literate person will integrate faster into society and find a job,” said Amangeldy.

“I took a basic sign language course to better understand the problem, and I use this knowledge in my work. Artificial intelligence allows you to process large amounts of data, filtering out the information you don’t need. My main objective is to ensure that people who are deaf or hard of hearing can benefit from the results of our project,” she added.

With no official sign language in Kazakh, the deaf community cannot communicate widely, depriving them of a chance to participate fully in society.

“According to official statistics, there are 33,000 people who are deaf, hard of hearing and have challenges with speech in Kazakhstan, but unofficial estimates range from 80,000 to even 200,000. In my opinion, these people are nearly invisible in society, and their challenges often go unnoticed. When I first introduced my project to people who were deaf and hard of hearing, they said, ‘We have far more urgent problems.’ I believe that if we improve their literacy, they can participate more actively in society, and their problems will be solved,” said Amangeldy.

The barriers to social integration for people with hearing disabilities begin early in school, according to Amangeldy.

“For example, there are not enough specialists in kindergartens who can prepare these children for school. If they come to school without knowledge of sign language, it will be difficult for them to learn it quickly. Later, they simply graduate with a certificate, but they cannot continue their education or find a job,” she said.

“The problem starts from childhood. There are only three to four colleges in Kazakhstan adapted for sign language, and they only teach professions related to crafts and service. We should start solving the problem from kindergartens, paying attention to the literacy of these children,” added Amangeldy.

The Kazakh sign language project is in the testing phase. Amangeldy is contracting with institutions for people with hearing and speech disabilities to test the system.

“We are also working with educators in preschools and schools. I introduced them to sign language technology, but it needs to be adapted to the speech patterns of children who are deaf or hard of hearing,” she explained. “The key feature of our project is the use of artificial intelligence— a unique tool capable of processing vast amounts of data and making necessary adjustments. In this process, the support of expert educators who work directly with children is crucial.”

She said the project serves as a “bridge,” connecting people with typical hearing and those who are deaf or hard of hearing through AI-driven technology.

“That’s why we named it SignBridge,” she added.

Science in Kazakhstan

According to Amangeldy, support for science in Kazakhstan enables women to unlock their potential in the field.

“Thanks to the growing support for science, I’ve been able to bring my project to life. I’m living proof that science is truly supported in Kazakhstan. Researchers here receive a lot of support, and science is becoming an increasingly prestigious field, which motivates young people. As a researcher, I can confidently confirm this,” said Amangeldy.

“I have encountered situations when I was told, ‘It is too difficult to implement a scientific project, you’ll face challenges.’ They even suggested I abandon it. My position is as follows: I studied on a state grant, I won a research grant, and the state invested in my education – a responsibility to deliver results and give back. That is a serious commitment,” she added.

The article was originally published on Kazinform.