ASTANA – The Washington-based Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP) and the Council on Strategic Risks (CSR) examined Kazakhstan’s role in the changing threat landscape of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) as part of the Jan. 30 panel session. Panelists delved into historical insights and discussed the key aspects of scientific cooperation between Kazakhstan and the United States.

Bacteriological studies at the Central Reference Laboratory in Almaty. Photo credit: nrcv.kz.

Upon the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan found itself in possession of the world’s fourth-largest nuclear weapons stockpile and the large-scale biological weapons factory. The country disposed of and removed warheads, bombs, and nuclear explosive devices from its territory in cooperation with Russia and the United States.

Kazakhstan’s No to nuclear weapons

Kazakh nuclear non-proliferation expert Togzhan Kassenova, who is also a nonresident fellow in the CEIP Nuclear Policy Program, expressed appreciation to policymakers and diplomats of that time for their ability to work with different stakeholders.

The territory of the former Semipalatinsk polygon today. Photo credit: news.un.org.

“To implement strategic decisions, Kazakhstan needed two key partners – Russia and the United States. The Kazakh government didn’t have a full picture of what was remaining on its own land. Russia had the information. Thus, Kazakhstan worked very well with Russia in information cooperation and technical expertise, and, at the same time, with the United States, also in technical expertise and more importantly, the funding,” she said, referring to the Nunn–Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) program.

The purpose of the CTR program was originally to secure and dismantle weapons of mass destruction and their associated infrastructure in the post-Soviet Union states. The initiative, according to Kassenova, is undervalued. She noted the colossal contribution of its highly qualified specialists.

“Kazakhstan was the last republic to depart from the Soviet Union,” said Kazakh Ambassador to the United States Yerzhan Ashikbayev. Circumstances of that time posed a raft of legal, political, and technical challenges on security.

“I want to reiterate how much we cherish our cooperation with the United States. Of course, the United States was guided by its own national interest. Nevertheless, we’ve managed to run these trilateral and different multilateral efforts,” he said.

Ashikbayev mentioned the nuclear-weapon-free zone in Central Asia. The starting point in the process of gaining a nuclear-weapon-free status for the region was the decision of first president Nursultan Nazarbayev to close the Semipalatinsk Test Site (STS) on Aug. 29, 1991. Years later, by a resolution of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), August 29 was declared the International Day against Nuclear Tests.

The ambassador reminded the audience that the high level of radiation and contamination affected more than 1.5 million people. It is the outcome of the 456 nuclear tests (340 underground and 116 aboveground) conducted for more than four decades at the STS.

The U.S.-Kazakhstan cooperation and geopolitical concerns

Ashikbayev noted that Kazakhstan, the ninth largest landlocked country, is “probably the only country in the post-Soviet space that has agreed upon all of its borders.” The Central Asian country shares a 7,598-kilometer border with Russia and a 1787-kilometer border with China.

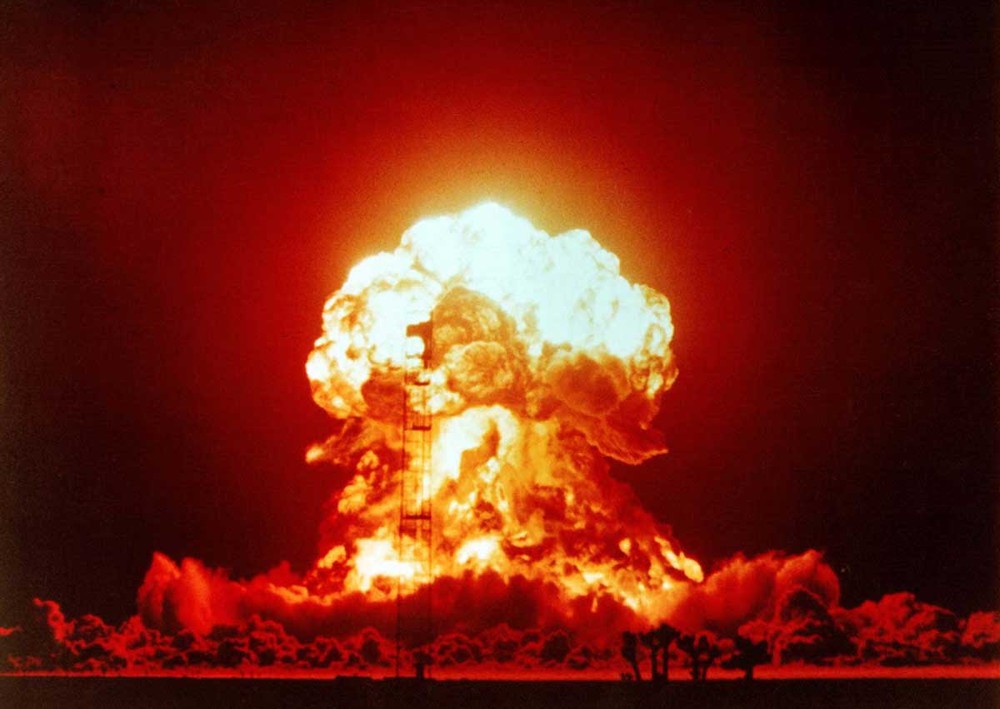

After closing the STS, Kazakhstan voluntarily gave up its fourth-largest nuclear stockpile, inherited from the Soviet military, including over 110 intercontinental ballistic missiles with 1,200 warheads. Photo credit: gazeta.ru.

“If Kazakhstan was to pursue a nuclear option, would you believe that both Russia and China would agree to these borders? That is an open question. Since we do have the totally demarcated and delineated borders with the two powers, the answer is evident,” he noted.

Andrew Weber, a senior fellow at the CSR on Strategic Risks’ Janne E. Nolan Center on Strategic Weapons, shed light on the origins of the U.S.-Kazakhstan scientific interaction.

“The amount of fissile material that was on Kazakhstan’s territory was extraordinary. There were tons of plutonium contained in the spent fuel at the reactor in Aktau in the Caspian Sea. That reactor operated to produce plutonium for the Soviet Union’s nuclear weapons,” he said.

Shannon Green, Yerzhan Ashikbayev, Togzhan Kassenova, and Andrew Weber. Photo credit: The Astana Times.

Weber recalled his involvement in Project Sapphire, a covert operation of the U.S. government in cooperation with Kazakhstan to reduce the threat of nuclear proliferation by removing nuclear material. Funded by the CTR program, the project, according to him, held reserves of 600 kilograms of 90% highly enriched uranium (HEU) at that time.

The Central Reference Laboratory in Almaty, a scientific center for ensuring biological security, lays more grounds for cooperation between Astana and Washington. Apart from life-threatening nuclear materials at the STS and radioactive sources left by the Soviet legacy for military, research, and industrial purposes, biological weapons were also produced in Kazakhstan. They were tested at Vozrozhdeniye Island in the Aral Sea.

The expert considers the laboratory as the result of “an amazing partnership between Kazakhstan, the United States, Germany, and other involved countries with a noble goal to improve public health and to stop infectious diseases.”

Similar facilities operate in other countries across the CIS region, including in Uzbekistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Ukraine.

The laboratory was created within the executive agreement on the elimination of infrastructure for WMD between Kazakhstan and the United States, and is one of the main tools for strengthening biological security, national scientific and industrial potential. Established in September 2016, the center belongs to Kazakhstan.

Based on multivector foreign policy, Kazakhstan’s denuclearization model allowed the country to take up the leading position in disarmament, non-proliferation, and peaceful use of atomic energy. Given the transboundary nature of biological threats, the center serves as another indicator of Kazakhstan’s openness to international cooperation towards peace and security.