ASTANA – Kazakhstan commemorates 165 years of Shakarim Kudaiberdiuly, a prominent poet and thinker who sought to uplift the conscience of the 19th-century Kazakh nation by delving into the themes of good and evil, human dignity and morals.

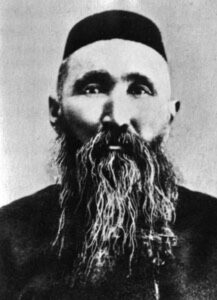

The only photo of Shakarim Kudaiberdiuly. Photo credit: e-history.kz

A prolific poet, commonly recognized and referred to by his first name, was the nephew of the great Kazakh poet Abai Kunanbaiuly. The foundations of his artistic nature were laid in childhood.

Born in 1858 to Abai’s elder brother Kudaiberdi, Shakarim grew up in a society where he could acquire a broad knowledge of literature, philosophy, history, geography and music.

At age five, he was educated by auyl (village) mulla from whom he learned Arabic and Persian literacy.

He lost his father, Kudaiberdi, who died from an illness when he was just seven. Despite becoming an orphan, Shakarim seemed to live in prosperity and contentment under the patronage of his powerful grandfather Kunanbai.

It was Shakarim’s poetic vocation that first showed itself. As a young man, he began writing poems on nature, ethics, good and evil, heavily influenced by his uncle Abai who introduced him to Western and Eastern literature, history, philosophy, music, rhetoric, natural sciences and geography.

“My poems of those young years were passionately honored by young people. But I did not know about the needs of my people and therefore could not say the right word at that time,” wrote Shakarim later in life.

Monument of Shakarim erected in Semei. Photo credit: rutraveller.ru

His passion for literature was organically combined with the desire to learn many skills. Being in Semei, Shakarim learned to play harmonica and violin, engaged in drawing and stone-cutting and made violins and dombras. His mother introduced him to sewing clothes. He also bred racing horses and engaged in eagle hunting.

As a young man of 20, Shakarim became a township governor, encouraged by his noble descent.

His beliefs as a governor in the 19th-century Kazakh lands led him to seek social justice in a country that had experienced oppression from the tsarist rule for many years.

However, faced with the hardships of the Kazakh people and the unfair administration, he lost faith in the system and turned to poetry writing. Shakarim described doubts and mental torment of that period in the poem “Life of the Forgotten.”

Forty years of age in 1898, Shakarim threw himself into a life of writing.

He was shaped by the poets Hafiz, Fizuli, and Navoiy, as well as George Byron and Alexander Pushkin, but his greatest influence was Lev Tolstoy, with whom he had correspondence.

His Kazakh translation of Hafiz and Fizuli’s poem “Leyli and Majnun” is still unmatched. Pushkin’s prose works “Dubrovsky” and “The Snow Storm” were translated and published in 1936 in poetic form by Shakarim.

He wrote two acclaimed poems, “Kalkaman-Mamyr” and “Yenlik-Kebek” (Kazakh names), glorifying pure love and condemning the brutal and obsolete orders established by the country’s authoritarian rulers.

In later years, Shakarim increasingly shifted to philosophy because it tackled questions about the purpose of life and man’s dignity as the most important subjects. His interest in ideas seemed, in part, a journey of self-discovery.

“The foundation of a good man’s life should be honest labor, a conscientious mind and a sincere heart. These are the three qualities that should rule over everything. Without them one cannot find peace and harmony in life,” wrote Shakarim.

The poet wrote “The Three Truths” treatise, which took him 30 years to complete. The treatise presents a three-way approach to understanding the world through materialism, theology and conscience. The most important insight for Shakarim in that work came from the fact that the essence of being lies in the conscience of each person, the primary need of the human soul.

In 1903, he became a member of the Semipalatinsk submissions of the West Siberian Department of the Russian Geographical Society, the continuation of an impressive academic career.

In 1906, in pursuit of spirituality, he traveled to Mecca for Hajj, an Islamic pilgrimage, followed by his trip to Cairo and Istanbul, where he attended libraries and read books related to the history of the Kazakh people. He mailed many books purchased there to Semei.

Shakarim was an outspoken humanist, always on the side of justice, no matter how difficult that could be. He and Abai Kunanbaiuly stood out during the decades of tumultuous change in the Kazakh society.

In 1912-1922, Shakarim pulled back from society to serve the greater good and devoted himself entirely to science and creativity. From 1922, he lived in Shakpan town in complete solitude.

He was shot on Oct. 2, 1931, without trial falsely accused of leading the anti-Soviet rebellion. Despite Shakarim’s rehabilitation in 1958, the poet’s works were prohibited for many years.

Kazakh writer Mukhtar Magauin gathered Shakarim’s dispersed literary works and published them in 1973 and 1988, ensuring the preservation and accessibility of Shakarim’s legacy. The full collection of his works was published for the first time in 1989.