Historically, Central Asia and India interacted more than 2,000 years ago. Thus, the establishment of the power of nomadic Khans in the Central Asian region, and later in a number of neighboring countries and the constant threat of invasions of India played a significant role in consolidating the Delhi Sultanate formed here at the beginning of the XIII century, the ruling elite which was represented mainly by the Turkic military-feudal nobility, conquerors and immigrants from Central Asia, Iran, Afghanistan. The Delhi Sultanate, which lasted 320 years, was the largest state in North India. One of its first founders was Qutb al-Din Aibak representative of the Mamluk dynasty so-called slaves.

Bulat Sarsenbayev

Qutb al-Din Aibak, the first sultan of the Delhi Sultanate was a slave, but thanks to the fact that he was bought by a famous scientist and judge, he received an excellent education and was able to master a weapon perfectly. After the death of the owner, his sons, expressing distrust of Aibak and concern about his growing influence, again sold him into slavery. Then the talented and educated slave is bought by the last sultan of the Ghurid dynasty, Shihab ad-Din Muhammad Ghori. Qutb al-Din becomes the first commander and governor of the Sultan in Delhi. Most of the sources mention Turkestan as the homeland of Qutb al-Din Aibak. Most likely, medieval authors had in mind the so-called country of the Turks – in the land, which included part of the territory of modern Kazakhstan. In most cases, historians claim that he comes from a Turkic Kipchak tribe. At the same time, the question of the origin of the Kipchaks themselves is rather complicated. It is important to emphasize that the Kipchaks became the unifying term of other Turkic tribes. Geographically, almost the entire territory of modern Kazakhstan was the domain of the Kipchak possessions, which was called Desht-i Kipchak (Steppe of the Kipchaks).

Sultan Muhammad Ghori. Photo credit: Humanhistoryinbrief.net.

After the Kipchaks began to move to the West, other Turkic tribes that came to the lands of Desht-i Kipchak continued to be called by neighboring people Kipchaks by the name of the territory they inhabited. In June 1206, after the death of Sultan Shihab ad-Din Muhammad Ghori, power in the state weakened so much that the dynasty was interrupted. At the same time, Qutb al-Din Aibak declares himself the fullfledged sultan of the independent Delhi Sultanate. Having become a sultan, Qutbal-Din laid the foundation for about a hundred years of rule in the Delhi of the Turkic slaves and their descendants, conditionally united in the “dynasty” of the Ghulam (slave). Despite the fact that he was a sovereign ruler for four years only, he managed to do a lot for his country. He introduced a generous payment for the military, for which they even called him “Lakh Bakhsh” (giving hundreds of thousands of coins), significantly reduced taxes for the Muslim population of the country. Aibak improved the administrative system, despite the dissatisfaction of many aristocrats.

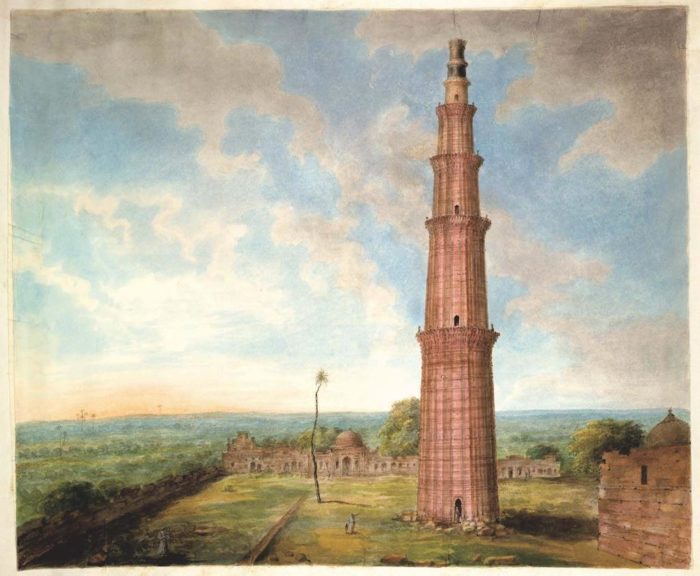

The official language of the country becomes Farsi. Many works of literature and architecture are created within his board. In particular, Lal Kot (“Red Fortress”) and Qutub Minar, which became the symbol of Delhi and India as a whole, have come to the present day. Qutub Minar is a 73-meter structure built by several generations of rulers of the Delhi Sultanate, a unique monument of medieval Indo-Islamic architecture. The tallest tower in India, the tallest brick minaret in the world, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In the Middle Ages, Qutub Minar was considered one of the wonders of the world. In 1210, Qutb al-Din died, falling from his horse while playing a game of horse polo (chovgan). Unfortunately, at that time, the sultan had three daughters and only one son named Aram-Shah, who was completely incapable of governing the state. Despite this, the nobility of Lahore declares him a sultan, but he is not interested in politics and does not know how to control the army.

Qutub Minar is the symbol of Delhi and India.

As a result, he was overthrown by the brother-in-law (husband of his sister) Shams ud-Din Iltutmish (1211-1236). Shams ud-Din Iltutmish experienced almost the same fate as his father-in-law. He also came from a noble Kipchak family, but was sold into slavery in early childhood. He was bought by Qutbal-Din Aibak, to whom he was subsequently very devoted and helpful. Then, he married one of his daughters Turkan Khatun, who was highly educated and knew Persian. However, the father did not find the courage to leave the management of sultanate to his daughter. In some ways, he was undoubtedly right, as he himself ruled for only about four years, and for further strengthening the country he needed a tough man’s hand. Iltutmish, who stood at the head of the Delhi Sultanate for 25 years, became such a Sultan. During his reign, the borders of the Sultanate were greatly expanded; moreover, he was recognized as a sovereign ruler by the Caliph. Also, the first attempt was made to penetrate the lands of Hindustan of the Mongols of Chingiz Khan, but they soon returned, leaving the sultanate intact. At that time, the war with the Mongols was avoided. Some historians place this credit for Iltutmish, since they obviously had diplomatic contacts.

Qutb al-Din Aibak (1206–1210)

Also, like his father-inlaw Iltutmish was engaged in construction a lot, patronized science and art. After the death of Iltutmish, power over a stable, prosperous and highly cultured state was to be transferred to one of his sons – the eldest Ruknud-Din Firuz, or the younger Muizud-Din Bahram. However, knowing the shortcomings of both sons, Iltutmish made an ambiguous decision: he appointed the daughter Razia, the eldest of the Sultan’s children, who had high-willed qualities to be appointed by the Sultan. Similar decisions were in the traditions of the Kipchaks (Turks). Since childhood, Razia studied archery, military strategy and often accompanied her father in his military campaigns. Father, spending a lot of time in the war, also trusted Razia to govern the state.

Despite the will of the Sultan, part of the nobility and the viziers were unhappy with the idea of appointing a woman to the ruler of the state. So, they raised the half-brother of Razia Ruknud-Din to the throne, and his mother Turkan Khatun became the de facto ruler. This caused a split among the representatives of the nobility and the palace plots. Razia understood that it would not be easy for her to get the power bequeathed by her father, although she had all the rights to do so. She called under the banner of his father’s comrades-in-arms, those who wished to continue the policy of the late Sultan. Five months after Ruknud-Din’s accession to the throne, the army began to complain about the incompetent leadership, and the provincial population protested against the ignorance of the rulers. Razia decided to appeal to the people of Delhi during Friday prayers. She came out in front of the people and reminded them of the will of her father, of her right to rule the state, and also that only the people can deprive her of the right to the throne if she decides that she is unable to govern and lead to prosperity. Delhi residents supported Razia and in November 1236 she was proclaimed ruler, becoming the first and only woman who ascended the throne of the Delhi Sultanate.

Shams ud-Din Iltutmish (1211-1236)

The overthrown Ruknud-Din was captured by her emirs, placed into prison and killed. Fearing the disloyalty of the nobility, Razia staked on personally loyal people, surrounding herself with Mamluks and former slaves, who owed everything to her. For example, the Ethiopian Malik Jamal ad-Din Yakut Haji became her vizier. This caused discontent of people from the Turkic environment. They began to accuse Razia of violating Sharia law, since she herself gave them a reason for this: she wore men’s clothes and a turban on her head, ordered to call herself a male Sultan as a title, openly resolved state affairs without closing on the female half of the house.

But the real cause of discontent of the Turks was different: The Turkic nobility in the Delhi Sultanate was a closed oligarchy and claimed full power, not intending to give up its privileges and not wanting to obey the autocratic power of the ruler. And although the chronicles describe Razia as a great, insightful ruler, a fair, beneficent patron of scholars, doing justice, caring for her subjects, possessing military talent and endowed with all the remarkable qualities necessary for the ruler, she was not destined to remain in power for long. 1240 became fatal for Razia: the insurgent nobility broke her army and captivated her, but if she managed to escape from captivity and gather new forces for the first time, then for the second time, on 13 October, 1240, Razia and her husband Malik Ikhtiyar-ud-din Altunia were beaten and captivated. On 14 October, 1240, they were both executed near the city of Kaithal (located in the north of India). Of all the Sultans of the Delhi Sultanate, the name of Razia is perhaps the most frequently mentioned in folk culture even eight centuries later. There are a lot of poems, plays and stories were written about her, as well as many films were shot. In conclusion, I would like to note that contacts of the Turkic world with Northern India and India as a whole existed for a number of centuries. These ties originate from the famous Kanishka, who ruled the Kushan kingdom at the beginning of the II century and contributed to strengthening the position of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent and Central Asia.

It is also impossible not to say about the nomadic Hun tribe who came to the territory of India from Central Asia in the 5th century, who later became the sovereign rulers of North-West and Central India. One of the special epochs for the history of the Indian people is the time of the Mamluk dynasty and the Delhi Sultanate in the XIII-XVI centuries. In addition, it is important to mention the Baburids, or, as they are called the Great Mughals, the Timurid state that existed on the territory of modern India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and south-eastern Afghanistan in 1526-1540 and 1555-1858. Great immigrants from the Central Asian region carried out numerous reforms in India. They touched on the tax system, military affairs and administration. These changes proved to be very useful for the development of the country.

In this regard, it is very necessary to talk about the activities of these individuals and about themselves. It is important to note that the tribesmen of the Delhi Sultans, such prominent personalities as Sultan Beibars and his descendants also created powerful states far beyond the borders of their homeland. In general, according to the findings of scientists, if we combine the time of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire, then in the history of India we can distinguish 500 years of uninterrupted Turkic era.

These ties originate from the famous Kanishka, who ruled the Kushan kingdom at the beginning of the II century and contributed to strengthening the position of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent and Central Asia. The Turkic nobility in the Delhi Sultanate was a closed oligarchy and claimed full power, not intending to give up its privileges and not wanting to obey the autocratic power of the ruler.

Author is Bulat Sarsenbayev, Ambassador-at-large, MFA of Kazakhstan, Former Ambassador of Kazakhstan to India, 2014-2019, PhD in History.