Abai’s works, including his most famous book “Kara Soz” (Book of Words), which consists of 45 brief parables and philosophical treatises, have been translated into many languages. Interest in Abai’s work is growing. The number of his followers and promoters is increasing as well as the number of books about him in print. Every person knows Abai in Kazakhstan. He is the alpha and omega of national culture, whose thoughts and works resonate through the ages, primarily because his philosophy touched on some of the deepest questions of human life. His philosophy is true and simple, deeply personal and widely political.

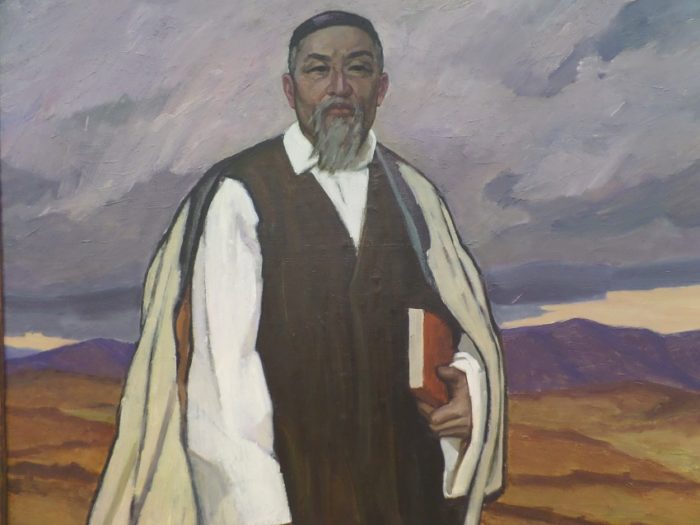

This year marks the 175th anniversary of the great poet, philosopher and enlightener Abai Kunanbayev (1845–1904). The anniversary is celebrated not only in Kazakhstan, but also on the international level, including at events under the auspices of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The main event will be held in August in Semei – the homeland of Abai.

A Genius of International Fame

Abai’s works have stood the test of time. Russian poet Anna Akhmatova once wrote the same about Alexander Pushkin. Abai lived and worked in the 19th century and in the beginning of the 20th century. He died in 1904. Now his works and life are of interest to millions of people around the world.

Bakhytzhan Kanapyanov

His works were not published when he lived, except for two poems released in the Omsk newspaper. After the death of the great poet, his nephew Kakitai Iskakov and his son Turagul gathered all Abai’s poems in 1905. Murseit Bikeiuly, who knew calligraphy handwriting, rewrote all the verses and songs of the poet within a month. They collected the works known by people residing in the villages of Zhidebai, Borili and several other villages near Semei. Abai’s pupils are representatives of the creative intelligentsia of Kazakhstan including Alikhan Bukeikhan, Akhmet Baitursynuly, Myrzhakyp Dulatuly, Magzhan Zhumabai and young Mukhtar Auezov. They dedicated their lives to helping Kazakhstan find its right place in the new era. They also wanted the world community to learn more about the wisdom and talent of the founder of Kazakh literary language. In 1909, the first book of the poet in the Kazakh-Chagatai language with Arabic script was published in St. Petersburg. The entire circulation – approximately 1,000 copies – was sent to Semei. This marked the beginning of Kazakh written literature in the 20th century.

Abai’s poems and aphorisms were widely known among people long before the first book came out. Every Kazakh had a dombra, a traditional string instrument, because Kazakh people loved the music it could produce. It shows how Kazakh folklore has been preserved and has survived to this day. Abai found the path to the heart of his people. He, firstly, was brought up on Arabic and Persian poetry, and secondly, he understood that he could convey to every Kazakh the translations of the world’s great poets, primarily Pushkin with the help of the dombra. Indeed, “Tatyana’s Song” from the “Eugene Onegin” novel was known in the Kazakh steppe. Abai also worked with verses of Lermontov’s prose work titled “Vadim.” He translated the poetry of Ivan Bunin for his people, which was banned until the very last day of the Russian writer’s life in 1956.

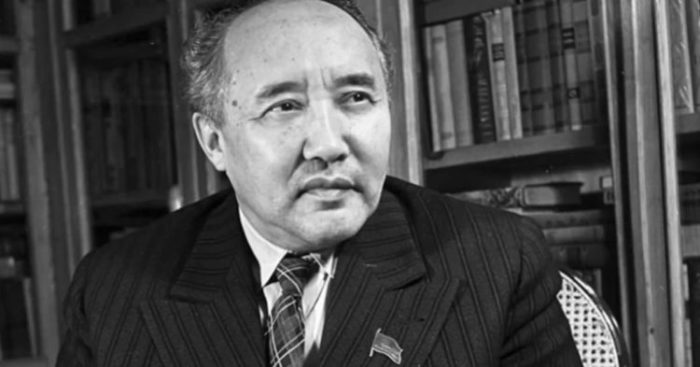

Mukhtar Auezov

No matter what language Abai’s works were published in – Arabic script or Latin – it had always been in demand. In the second half of the 19th century, at the beginning of the 20th, and now, in the 21st century, people see many parallels in the ideas Abai put forward.

In 1940, Kazakh writer, scientist and playwright Mukhtar Auezov wrote the first book about Abai “The Path of Abai”, which was included in the Library of World Literature. Five years later, in 1945, in honour of Abai’s 100th anniversary, Khudozhestvennaya Literatura (Fiction) publishing house released “Kara Soz” book translated by Victor Shklovsky. After this, the work became known as “Edification.” It was this translation that was later reprinted twice in 1954 and 1979.

In 1970, Kazakh writer Satimzhan Sanbaev released his translation of the book titled “Words of Edification” and in 1993, a famous Kazakh writer Rollan Seisenbaev attempted to present the text of the famous work in German by publishing it under the title “Book of Words.”

I was one of the compilers of Abai’s texts, which were published in 2019 by Zhibek Zholy (Silk Road) publishing house. Now, as you know, the works of Abai are translated into many world languages.

The Secret of Abai’s Success Today

Abai helped develop the Kazakh national identity through writing and art. Living at the end of the era of the nomads on the Kazakh steppe, he incorporated many elements of the history of both Kazakh and Russian peoples. He loved his people, he loved Russian literature, he was harsh and critical of the new order being formed in Kazakhstan and we see these feelings expressed in his poems and novels.

Abai was confident that unanimity was better than monolingualism, and I completely agree with him. Abai believed that words could unite people in their worldview. An excerpt from one of his works:

“… Millennial wisdom of treatises,

Does not embellish the deception,

Does not hide the soul’s immoral flaw,

Does not help hide your sins under the robes.”

Abai shares his views on the problems of history, pedagogy, morality and the law of the Kazakhs. Bishop Gogolev and Father Gennady, in trying to convey to the readers the beauty and philosophical depth of Abai’s work, wrote down his poetic version of the “Words of Edification.” This is how common ground between the postulates of Christianity and liberal Islam were found. The first words of Abai are very important, they set the tone for all further narration – philosophical, consonant to the state of mind of those who have already lived and understand many things about life.

Abai’s works are not about “dividing and conquering”, but rather about “uniting.” This was an especially important idea at the beginning of the 20th century. He tried to convey to his people to seek greater unity, and was like Pushkin, ahead of his time in this regard. We can say that his poems are like patchwork, or as the Kazakhs say, “kurak korpe,” which created the spirit of the flourishing Kazakh steppe. Abai also employed moral criteria that is sorely lacking in our time.

He received his primary education in a madrasa, a religious school. He learned the Russian language himself thanks to the library in Semei opened by exiled revolutionaries. Abai began studying the works of not only Russian, but also Western European classics of literature and philosophers. He strove to find his place in the world, understanding that acquiring knowledge was absolutely essential. He felt his purpose in life very keenly and he knew and understood that he would be useful to the Kazakh people during the period of turbulence and reform that lay ahead.

Abai’s amazing love lyrics are known to Russian readers due to translations of the schools of Vsevolod Rozhdestvensky and Mukhtar Auezov. For example, his poem “A night without wind in the moonlight…” (“Zhelsіz tunde zharyk ai…”).

Abai became a reformer of the Kazakh language and the founder of the Kazakh written literature. And now, of course, one of the sides of our country’s sovereignty is the names of those who worked under his influence. He was a supporter of the principles of the Enlightenment, and for Kazakh people who were illiterate for most of their history, these ideas were inaccessible. The painful transition to a settled way of life in the second half of the 19th century and the decline of the nomadic civilization are well described by Mukhtar Auezov, who also introduced the concept of the “good and eternal” to the Kazakh people.

To love a country as Abai describes it, is to be self-critical both in relation to oneself and one’s own people. The key to a bright future is to think deeply about the problems facing one’s nation and one’s people.

Unfortunately, after the collapse of the USSR, people were only thinking about how to become rich. Now when I talk to different people, especially young people, I see that a sense of spirituality is reborn in them. Spirituality can survive centuries of all kinds of cataclysms, and for this to happen, continuity of spirituality is necessary. The whole world, and not just the Kazakhs, will need spiritual guidance going into the 21st century that perhaps people like Abai were able to provide.

Abai: A Personal Story

I was born to a family of teachers. We always had a big library at home and when friends and relatives or colleagues of my parents gathered at our place, Abai’s words “be the son of not only your father, be the son of all mankind” were always quoted and discussed. And these were not just simple words, but words that brought meaning to my life.

I am a Kazakh, and like all Kazakhs, I know a little about Abai. Abai’s works are at the core of Kazakh spirituality. It is probably impossible to imagine the Kazakh people without Abai. It’s funny, but Kazakh mothers will often chide their children with warnings to “be careful!”, which in Kazakh sounds something like “Abaily bol!” But this may also be understood as “Be Abai!” So you could say that Abai’s name is tattooed into Kazakhs’ DNA from an early age. And his poems and lyrics describe the inner world of Kazakh people. There are lines that are difficult to translate while preserving the melody and spiritual significance, but every Kazakh knows these words since his or her childhood. Sovereignty in the 21st century for Kazakh people is closely connected with Abai.

According to Murat Auezov, the Dzungars did not have their own poet like Abai, therefore because of this, the nation does not exist today. Kazakhs, on the other hand, have Abai, therefore, they continue to exist in this century. Abai devoted himself to the Kazakh people, so he became an integral part of this people. He is the center of the Kazakh Universe, and his homeland, Semei (until 2007 it was named Semipalatinsk) is the spiritual capital of Kazakhstan.

Abai combined European culture with the culture of the Kazakh steppes and was not simply immersed in his own world, but shared his wisdom and knowledge with people, thereby creating a culture for other Kazakh people.

I started to translate Abai’s works and create films and articles about Abai. He came into my life and stayed there forever. I knew a lot about Abai thanks to the writer and scholar Mukhtar Auezov and the way he describes Abai’s life in his famous book “The Path of Abai.” Mukhtar Auezov spoke in his book about one trial where Abai delivered a speech. The poet’s speech was an attack on all those present – both the winners and the defeated, as well as the judges, to whom he showed their arrogance.

People say that Abai created Mukhtar Auezov, and that Mukhtar Auezov brought Abai’s works to this world. I have studied Auezov’s works and I have learnt a lot about Abai as well as others. By the way, Auezov also made the writer Chingiz Aitmatov famous after he published an article on the work of the young fellow writer in the pages of Literaturnaya Gazeta (Literary Newspaper). Aitmatov used to say that after leaving his native land, he always carried two names in his heart – Manas and Auezov. The main reason for their recognition is the four-volume novel by Mukhtar Auezov “The Path of Abai.”

Every person has something to say or write about Abai on the eve of his anniversary. As for me, I released the full collection of Mukhtar Auezov’s works in 50 volumes and published the compilation of books by Abai in Kazakh and Russian. Also, I also published the works of the repressed poets and Abai’s students – Shakarim Kudaiberdiuly, Magzhan Zhumabai, Myrzhakyp Dulatuly, Akhmet Baitursynuly.

Author is Bakhytzhan Kanapyanov, Kazakh poet and translator.