ASTANA – California native and Kazakh TV’s Discovering Kazakhstan host Dennis Keen has lived in Almaty for six years. It was in his adopted city that Soviet monumental art first caught his eye.

Keen, who spoke about the country and its art in an interview with The Astana Times, was just three years old when the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991.

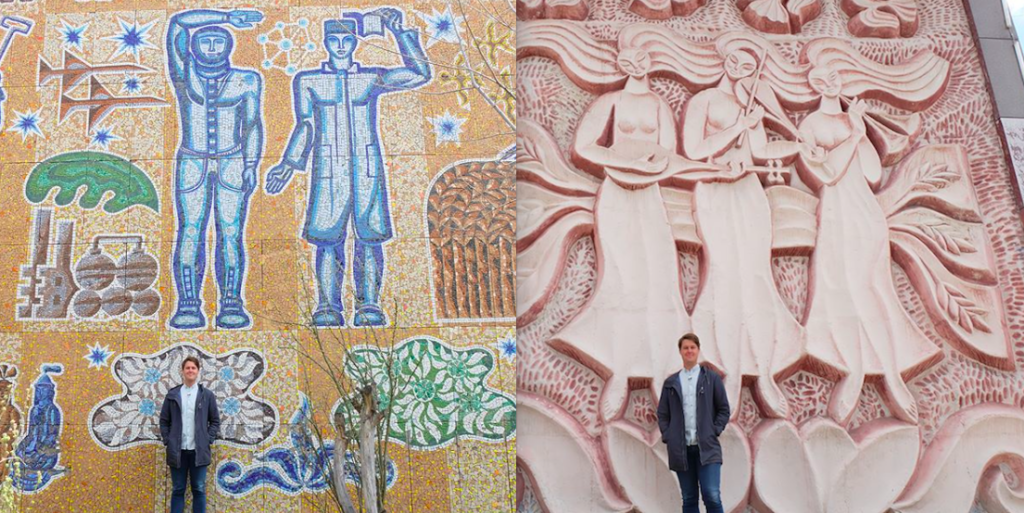

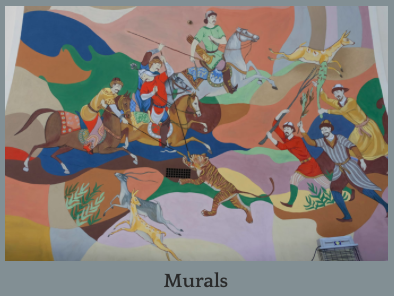

“People notice things that are new to them and, growing up in the United States, we never had art like this in our public spaces,” he said. “There are many murals in Los Angeles, where I grew up, but mosaics especially have such a physicality to them that they made a strong impression on me.”

Socialist realism was the Soviet Union’s official art style from 1932-1988, but he sees Soviet monumental art as more stylised than realistic.

“Because monumental art was considered decorative art rather than fine art, monumental artists were often given more stylistic freedom than their colleagues who were easel painters – that may be one aspect that is leading to a reappraisal of Soviet monumental art,” he noted. “Perception of this kind of art is also changing with time, as the Soviet era recedes into the past and people can more neutrally evaluate its legacy.”

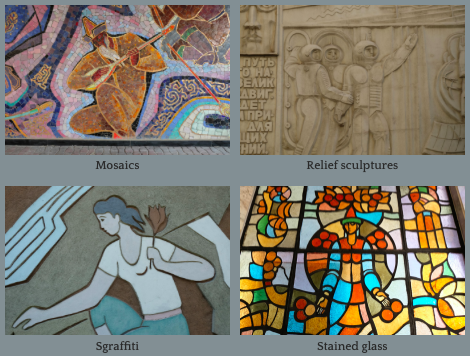

Since 2017, the Stanford graduate has systematically and digitally documented Almaty’s mosaics, sgraffito, murals, relief sculptures and stained glass through Monumental Almaty (http://www.monumentalalmaty.com). He and his team of volunteers have brought the country’s only large-scale pietra dura mosaic, a pedestrian tunnel bas-relief and mosaic in the village Terekty, back to life.

“Seeing all the artwork in one place allows people to realise just how much monumental art there really is and just how beautiful some of it is and gaining that understanding and appreciation is the first step toward preserving it,” said Keen.

Monumental Almaty and Archcode Almaty researchers, who have a shared approach towards advocacy, recently mapped and documented the city’s unique mosaic bus stops to convince local authorities to stop demolishing the architectural landmarks and work towards their preservation.

“Popularisation and education are important in order to effect change,” said Keen. “The public needs to understand the subject, such as the history and importance of these bus stops, before we can ever expect them to want to do anything about it.”

Accordingly, discovering monumental art in Almaty is merely the first step. He also researches who made the art, how and why. Monumentalisty (mural artists) came from all corners of the Soviet Union in the 1960s-1980s to create monumental art in Kazakhstan and after decades of anonymity, are given credit on the website.

“The journalist Svetlana Romashkina first gave us the contacts for Vladimir Tverdokhlebov, the artist of the famous Zodiac Fountain, who has been our biggest supporter,” he said on tracking down artists through Tverdokhlebov and Almaty’s Union of Artists. “It’s always gratifying for artists to see that people are interested in their work because they often feel that the greater public has forgotten about them and left them behind. During the Soviet Union, the government supported monumental artists quite well and now, many of them struggle to get work.”

Keen invites town and city residents to contribute to a digital map of Kazakhstan’s monumental art on the website and Instagram (@monumentalalmaty).

“In March, I’ll be traveling to Astana, Pavlodar, Semey, Oskemen, Kokshetau, Petropavlovsk, Kostanai and Karaganda to document monumental art there for a new project,” he said. “There are many bas-reliefs and mosaics, for example, in lobbies, auditoriums and factories that I will never find unless someone tips me off. People can also stay vigilant and keep an eye on their favourite artworks to warn us of any possible renovations or demolitions and they can join us in petitioning the authorities to protect more works of art.”

Since 2013, Keen has also documented Almaty’s architecture and urban landscape through his Walking Almaty project (www.walkingalmaty.com), Facebook and Instagram (@walkingalmaty). He was featured in The Astana Times in 2016.

“People have mostly responded to the effect of ‘I never realised what beauty we have!’ Cultivating this kind of appreciation is really important to me and I hope that it leads people to be more engaged in their environments,” he said.

Sgraffiti by an unknown artist at Abay National Pedagogical University’s Institute of Arts. Photo credit: monumentalalmaty.com.