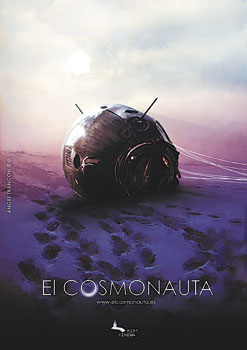

25-year-old Spanish filmmaker Nicolas Alcala has made a crowd-sourced film that he is returning to the crowd not as a finished product, but as an ongoing collaboration. The film’s license allows other people to copy, edit, remake, cut and reuse his film about memories, desires and lost cosmonauts as they see fit. Alcala spoke to The Astana Times about his inspiration and how he created this unusual film.

The film is set in Kazakhstan, isn’t it?

No. There are some scenes that are supposed to be at the cosmodrome, but they aren’t. They were shot in Latvia, actually. We wanted to shoot here, but it was really expensive and we couldn’t afford it. If we shot the film in a traditional way, it would cost 6-8 million euros.

No. There are some scenes that are supposed to be at the cosmodrome, but they aren’t. They were shot in Latvia, actually. We wanted to shoot here, but it was really expensive and we couldn’t afford it. If we shot the film in a traditional way, it would cost 6-8 million euros.

Did you inquire about the cost of shooting a film in Baikonur?

Yes, I think the producers talked to them. It was not only what they charged; that was a regular amount. But to move 10 people and equipment to Baikonur—it would be really expensive. All the visas, all the permissions. We couldn’t afford it. It was really sad when we found out that we would not be able to shoot the film there …

[Chairman of the National Space Agency] Talgat Mussabayev and 25 other people from the agency will be at the premier. The agency really supported us at the presentation.

Can you tell the story of the film’s funding and of how you shot the film?

Basically, we started this project almost five years ago; we were just kids wanting to make a film. We were students; we were 21 years old. We didn’t have connections with the agency, and even if we tried to tell them that we wanted to make a film about the space race in Russia, shot in three countries with English actors and a lot of special effects, it wouldn’t have worked. Even though the idea was great, not a single producer in Spain would bet on it. Besides, we wanted to do this film in a really innovative way, we wanted to do crazy things like the book or USB. And the only way to do that was to have financial freedom. That’s why we wanted to try crowd funding and we read online that there were a few projects out there using it. And we said “Why not? Let’s try it and see how it works.” So we put our 20-page draft of the screenplay online and we said to people, “if you give 20 euros you’ll get a T-shirt, and if you give this amount you’ll participate.” It was a hit. We raised more than half a million dollars from 5,000 people.

Then we decided to distribute the film in an innovative way; that’s why we did the premiere of the film on television, in movie theaters, on DVD and on the Internet at the same time. And we’ve got a creative license that allows people to legally copy the film, to share it, to screen it if it’s not for profit or even to remake it. They can change it, they can re-edit it, they can use parts of the film for their own work. And beyond that, we did a transmedia project. It’s not only a film, it’s a whole universe: a story told over three hours through 36 short ones, a feature film, a book, on Facebook, that tells the audience the story that we looked at the universe and saw and wanted to tell.

Your film has the longest list of collaborators in the world. Why do you think that is? Why did so many people get involved in a project that they wouldn’t profit from?

We had two ways of collaboration. One of them was to buy merchandise: you could buy a producer’s certificate, if you paid 20 Euros you could get a T-shirt, you could pre-buy the DVD. So that was just buying. We have 4,000 of those, approximately. Then, we had other investors. With them, we signed a contract; they were expecting to make a profit. So we have 600 investors. Some of them put in 100 euros, some of them put in 80,000. I guess all of them are expecting to make a profit, but they knew it was a risky project, they know what was at stake.

What inspired you to do this movie?

The first time I heard about cosmonauts was in an article about a Spanish photographer’s project. The project was about many dark legends about how people there disappeared. Because Russia was really hidden; they hid everything they did and covered up the accidents. Everything was secretly hidden. That turned into a lot of legends; people talking about cosmonauts in space, getting lost. That there were people in space before Gagarin who died there and no one ever knew. Some of them were true, some of them weren’t, we’ll never know.

Actually the film starts with this: there were two Italian brothers, they were really in love with space, they had a big radio in their home and they happened to be on the trajectory that all the Russian rockets followed. So they were in Italy, but they were able to capture all the communications and at some point they became really famous because they captured the voice of a female cosmonaut re-entering the atmosphere, saying “I’m burning, I’m burning, this is really hot, this is really hot,” and then the communication was lost. Nobody knows whether it was fake or not. It gives you huge ideas when you listen to this, it is really frightening. After that, they became really famous and they found other legends about cosmonauts. This made me realise how powerful the image of a man alone is, 400,000 kilometres away from home, knowing he’s not going to be able to come back but still alive, watching his home, now really small, just there, being able almost to grasp it, but knowing he is going to die there alone. So this image really got me and I started to write a lot of stories about lost cosmonauts—and also about cosmonauts wandering into some places; that also ended up being a story. I’ve got this idea of a man lost in space that comes from the people who went to the moon. There’s Armstrong, Aldrin and the other guy—nobody knows about Collins. He is the one who stayed in the spacecraft when the two other walked on moon and basically when he came back he said “I’ve never felt so alone.” He was left on the dark side of the moon, the other guys were walking. And he said “I didn’t see Earth, I was in the dark, I didn’t communicate because the radio didn’t reach. I was completely alone in the universe,” and that feeling really changed his whole life.

What was the message of the movie? What do you want your audience get from it?

I don’t propose symbolism. I don’t like it, I don’t use it. It’s not about the idea; I want them to get the feelings, the emotions. To make them think whatever they want to think. I just want them to relate to the story I’m going to tell them. I think this story is about memories, about desires. I think all our lives revolve around these ideas. We spend our lives living things and not enjoying them, but living them to remember them later. After 10 years, you remember something as amazing, and you try to search for that feeling again and you’re never going to get it. That’s desire. We always have desires, and desires can never be achieved. We always say “let’s just keep moving.” Our lives turn around memories and desires and it’s difficult to create a balance out of that. How do we handle memories, how do we handle desires?

What’s your next movie going to be about?

I’m working on political stories. It will be a story that makes us think about how we live, how institutions work and how politicians work. It will be very optimistic, utopian. Like all the films I work on, it’s a feature film.

I was inspired by the story of Marina Abramovic, an artist who works in New York, very famous. She has done a lot of performances, really powerful ones, and in the 1970s she was really famous. She had a lover. When you see them together, they were like the biggest love of all time: really special. They did a lot of performances together. They did really powerful things. Over many years they moved around the world and at some point, even though they loved each other very much, they decided to split, and they never saw each other again. 25 years later, she was at a performance in New York. This was two years ago. She’s still very famous. So the performance was about her sitting in a chair for 48 hours. People were able to come and touch her hands, closing their eyes, staying there for a minute, sharing a minute with another person, with Marina Abramovic. She did that with 1,000 people. Then the guy shows up. It’s 25 years later. He sat down, he looked at her, she recognised him. They have this beautiful moment when she is not going to say anything. So the story is about how he holds her hands, stands there for a few minutes and then walks out. The story is going to tell this idea. This is again about memories and desires.

Your father is a painter. What does he think about you doing films?

He is really proud of me. He has seen my films. He is a great critic of my work. I had to learn how to handle what he says. When he came out of the premiere of my film, he said that he loved it and he said it was a terrific film. That was a pretty special moment. Now we are working together on some projects. Actually, his last project was about Traviata. I built a set with actors, a director and photography and we invited photographers to make pictures and directors to shoot scenes. We showed how he was creating his paintings. At the exhibition, we want to have a painting and the pictures that the paintings came from and the videos. So this is a video-painting project.

Do you want to go into space?

I’d love to. I think I’m going to. I think many people will want to. That’s not because I’m going to be very rich, to have 30 million to spend, but because in 30 years it will be a normal thing to do. Everyone will be able to do it on the weekend. I really think that’s going to happen. I’ve met a lot of people who have made me believe that will happen.

Have you met a Kazakh cosmonaut?

I will meet [Talgat] Mussabayev. I’ve met several Russian cosmonauts and some people who went to space. That was amazing. I asked them a lot of technical questions.

Do you think it is possible to make a movie like yours in Kazakhstan? Is it possible to find sponsors and people to support and promote the movie? What advice would you give aspiring filmmakers?

Well, five years ago this advice would not work, but I finally managed to shoot my film. If you watch the trailer, you’ll find out that it’s not like a Hollywood film. But it looks like one; the images, the camera work and everything else. And I did this with a 2,000-euro photo camera. We shot with a photographic camera. We shot with a Mark-2. Basically, we had nothing. Nowadays, you can tell an amazing story. You don’t need a great production, you just need a great story and a small camera. If you want to make a bigger film, the bigger it is, the more you need to compromise. You can find a sponsor for making a movie, some people to give you a couple million, which is more than enough to make a good film. Just find something that doesn’t make you compromise. Nowadays I would say just go and do a film, you can do it. Will it find support? Probably. If the government is smart enough, they will understand that they can and should promote films because that’s the way you promote your country. In the United States they did that in 40s, 50s, 60s. They understood that; they were going to tell the world about how good the U.S. was.