ASTANA – The United States-based textile artist Janice Arnold took felt as a starting point to explore its symbiotic relation with the culture of the nomads, connecting the cultural with personal effects through her widely varying works with felt. Felt, a highly functional textile art form, has been enmeshed in the Central Asian nomadic lifestyle for thousands of years.

Janice Arnold. Photo credit: Carlos Javier Sanchez, The Evergreen State College

Arnold spoke about the origins of felt, its versatility, the wisdom of nomadic felt-making practices, and her recent trip to a felt festival in Kazakhstan in an interview for this story.

Felt was the earliest type of fabric for many nomadic people. It served them well throughout their lives as clothing, footwear, home decoration, yurt exteriors, and horse blankets. For thousands of years, the nomadic felt-making tradition created a strong bond with nature and among community members.

According to Arnold, felt-making is a powerful ancient process, albeit often overlooked even by Kazakh people, whose ancestors were masters of practical felt application.

“Technology and our synthetic surroundings have separated us from the natural world and our historic traditions of making things by hand. We are tactile, social beings and have become starved for natural fibers, textures, and irregular forms,” said Arnold. “Sharing physical work together to make something larger than one can make alone, creates an emotional bond that is not only rewarding. It is an authentic experience of connection that creates strong social fabric.”

Much of Arnold’s textiles and artwork are inspired by her travels to Central Asia and the culture of the people and cities she visits, often exploring the ways in which the material could guide her as an artist.

The artist’s background and the first experience with felt

Sewing and textiles have always been part of Arnold’s life. The youngest of four children, she learned to sew by repurposing her siblings’ clothes, which became her first encounter with textiles and helped to develop a refined sense of fabrics.

Arnold made a standout piece from felt that is a “dragon fabric” for the “Grendel” opera premiere at LA Opera. The image captures the final dress rehearsal for the opera. Photo credit: Robert Millard, MillardPhotos.com

Arnold studied ethnic textiles in college and later started working in the fashion industry to undertake visual merchandising projects. But it was only when she was offered to make sculptures for the fashion windows by Nordstrom fashion retailer company in 1999 that she set out on the path of studying ethnographic felt-making.

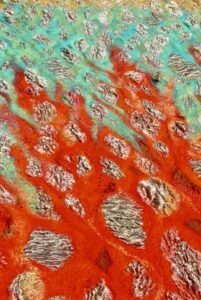

A close-up of the “dragon fabric” made of felt for the “Grendel” opera world premiere. Photo credit: jafelt.com.

“They saw a small sample of the handmade felt I made, and they said, ‘yes, we want 200 sculptures.’ Two meters tall 200 sculptures required more than 1,000 square meters of handmade material, and yet I’d only made pieces of felt the size of my hand,” said Arnold.

Describing her approach to challenges, she said she is a ‘real risk taker.”

“I grew up with this attitude of, it is not ‘can I do something’, but ‘how can I do something’,” she added.

“From the beginning, as I was exploring this textile art form, I had to go back to the traditional form, and the only people in the world making large sheets of handmade felt were Central Asians,” she continued.

At that time in the USA, handmade felt was basically unheard of, Youtube and Google didn’t exist. That is, to get her started, she found a National Geographic article with photographs of Central Asians laying the raw fiber on the ground and rolling the wool into felt behind the horse.

“Felt is not a singular kind of fabric, rather an expanding universe of textiles, with limitless potential,” says the artists’s website, which is reflected in this piece made of felt. Photo credit: jafelt.com

“Those photographs were my guides. It was all I had, and it was a matter of experimentation, making mistakes, and eventually succeeding by learning the language of the wool. I did not have a camel or a cow, or a horse, but I had a car and a family. I rolled the wool into felt behind my car. This was how the first 1,500 square meters of handmade felt was made in my studio,” said Arnold.

That experience turned her interests into a career. Arnold was one of the first artists in the US to create handmade felt on this scale for her art work. She later did large projects for Cirque du Soleil, Hollywood costume designers, Los Angeles and New York City Operas.

One standout piece from felt was the project to create a “dragon fabric” for the “Grendel” opera world premiere. “It had to emulate molten lava, tarnished gold and copper, and fire. I put all those elements together into meters of felt that became part of the set and lead costumes,” said Arnold, describing felt’s versatility.

Central Asian culture and felt

As Arnold developed her approach to working with felt, she often visited Central Asian countries to learn about regional textile traditions within the cultural context and to display her work and the versatility of felt with local masters.

“I immediately felt this bond with the indigenous people because this was an art form of survival thousands of years ago, and it was part of all phases of life. Felt really is a spiritual fabric. It is something that is so old, innate, and natural in its form that people have taken it for granted,” said Arnold.

Felt-making was always a community effort. For thousands of years, the nomadic felt-making tradition created a strong bond with nature and among community members. Photo credit: elana.kz

As simple as felt-making might sound, the nomads’ innovative approach to the “living fiber” that responds to the environment cannot be denied. “When it is a very moist environment, the wool fiber opens up and absorbs that moisture. That is why you can wear it in the summertime. Then in the wintertime, it will insulate you,” said Arnold.

The ability to learn how to collaborate and harness naturally occurring phenomena such as felt is miraculous, according to the artist.

“The real miracle is sheep, and nomadic people learned how to collaborate with the sheep’s wool to survive. This, to me, is the wisest thing in the world, that people can have this relationship with the natural world and work together with nature to survive,” said Arnold.

“Shepherds are taking care of the sheep, the sheep give the wool. It is a sustainable circle that humans have forgotten for so long. Now we are beginning to see the wisdom of it. So when I come back to Central Asia, I see it is the Central Asians who are the wise ones,” she continued.

According to her, traditional felt textiles are laden with meaning that should not be separated from the culture and its origins.

“To me, you cannot separate the people and the process from the product. I honor this indigenous art form and believe it is important to show gratitude for that and also to educate people. So whenever I give a lecture or presentation or do an installation talk, I always talk about the origins, talk about Central Asia, talk about nomadic wisdom and philosophy, how this fabric evolved, and also talk about the process and how the wool actually is a natural technology that deserves respect,” she said.

The artist’s visit to Almaty

Last November, Arnold visited Kazakhstan for the first time. The Union of Kazakh Artisans planned Kazakhstan’s first International Felt Festival in conjunction with her visit, where she gave several presentations and master classes.

“Cave of Memories: 43 degrees N x 76 degrees E” installation in Almaty with precise coordinates of the Kasteyev State Museum of Arts, where it was located. Photo credit: the artist’s personal archive.

“I am humbled by the beautiful felt that is made in Kazakhstan. I wanted to offer my personal respect for how they are continuing this important living tradition with so much integrity. In master classes, my goal was to help young people and felt masters together see the beauty in their tradition. I also offered ways to inspire and expand what they can make, and how to explore the potential of textures, weight and see new uses of felt,” said Arnold on her experience with local felt artisans.

While in Almaty and inspired by her visit, Arnold created the site-specific temporary installation with pieces from a series of long translucent panels. Each one was imbued with many layers of metaphor, connecting universal consciousness, family, memory, science, the cycles of life, and the concept of felt as a unifying force among cultures around the globe.

“I refer to these pieces as ‘nomadic’ – an homage to the ancient origins of felt. In keeping with tradition, these pieces are designed to be portable and easily hung to harmonize with each unique place and space,” said Arnold.

The installation also contained a video projection of the artist’s home, creating what she calls a “walk in my shoes” experience.

“For the past few years, I have been video documenting the seasons close to my home in Olympia and studio in Grand Mound, Washington State. Thanks to this collaboration with John Carlton, artist and video editor, viewers could walk in my shoes through this installation. This view offered a window into what inspires and nourishes my creative spirit,” she said.