ASTANA – The ethnic history of the Kazakh people is complex, shaped by centuries of migration, cultural interaction and political change across Central Asia. Modern historical sources and DNA research now offer new insights into how the Kazakh nation emerged and how traditional genealogies, known as shezhire, can be verified scientifically.

Zhaksylyk Sabitov, the Kazakh historian, political scientist and geneticist. Photo credit: Sabitov’s Instagram page

In an interview with The Astana Times, Kazakh historian, political scientist and geneticist Zhaksylyk Sabitov said that the Kazakhs formed as a unified ethno-genetic community in the late 13th century, during the era of the Golden Horde.

Sabitov has written more than 300 academic publications and specializes in the history of the Golden Horde and the Kazakh Khanate, as well as genetic genealogy. He leads the Research Institute for the Study of the Ulus of Jochi under Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

While trained in political science, Sabitov developed a strong interest in history from childhood, particularly in areas that remained underexplored. He chose three main research directions: the Golden Horde, the Kazakh Khanate, and the population genetics of Kazakhs and other Turkic peoples of Eurasia.

“These fields were poorly studied in the 20th century, which means there is still great potential for scientific discovery,” he said.

Links to the Golden Horde

According to Sabitov, Kazakhs are a relatively long-established genetic community. The physical and genetic traits of the Kazakh people emerged through the mixing of local Turkic populations, such as the Kipchaks, Oghuz, Karluks and Kangly, with nomadic groups from East Asia, including Turkic and Mongol tribes.

“If we look at the origins of the Kazakhs, we can analyze them from several perspectives. The first is physical anthropology. The well-known Kazakh anthropologist Orazak Ismagulov wrote that the physical anthropological type of the Kazakhs formed in the 13th century. It resulted from the mixing of incoming nomads from East Asia with local Turkic populations,” Sabitov said.

Bashkir geneticist Bayazit Yunusbayev later published research dating the formation of the Kazakh people as a unified ethno-genetic group to the 13th-14th centuries. His findings show that Kazakhs emerged from the mixing of local Turkic groups and incoming Turkic-Mongol populations from East Asia. These results align with both historical records and physical anthropology data.

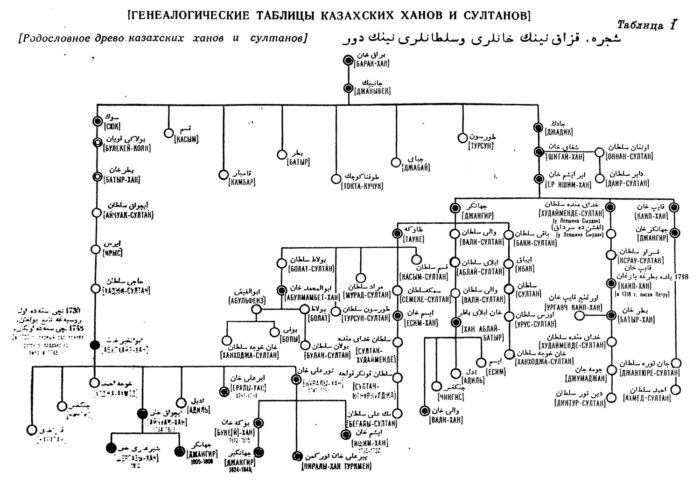

Shokan Ualikhanov recorded a genealogical table tracing the lineage of Kazakh khans and sultans from Barak, the ancestor of the three Kazakh zhuzes, based on oral accounts and historical sources. Photo credit: shoqan.kz

At that time, the term “Kazakh” had not yet existed, but the ethno-genetic and anthropological type had formed. Anthropologist Leonid Yablonsky compared modern Kazakhs with ancient populations and found that they were closest to the nomads of the Golden Horde.

“From a physical anthropology perspective, Kazakhs differed very little from the nomads of the Golden Horde,” Sabitov said.

Advances in population genetics later reinforced these conclusions. Studies of autosomal markers and Y-chromosomes indicate that many Kazakh clans descend from male ancestors who lived during the Golden Horde period.

“Around 70–90% of Kazakhs share male-line ancestors from that era. Many clans trace their lineage to Golden Horde emirs. Historical and genetic data point to the same conclusion: Kazakhs are among the heirs of the Golden Horde,” Sabitov said.

Verifying shezhire through science

Traditional Kazakh genealogies, known as shezhire, have long been central to Kazakh culture. For centuries, families memorized long lists of ancestors, passing them down orally or recording them in manuscripts.

Today, many Kazakhs actively trace their roots and preserve their family shezhire. This is one example of a family’s lineage embroidered in a modern interpretation. Photo credit: atategim.kz

In Soviet times, shezhire was often dismissed as myth or folklore. Today, genetics is giving it new scientific relevance.

“Shezhire is a multilayered phenomenon. Some parts are symbolic or legendary, but many reflect real biological relationships. DNA allows us to verify which is which,” Sabitov said.

According to him, most clan-level genealogies align closely with genetic data. While broader origin stories, such as the notion that all Kazakhs descend from three legendary brothers, are largely mythical, the structure of individual tribes often aligns with genetic evidence.

For Kazakhs, shezhire was never just about bloodlines. It also shaped social order, marriage rules, leadership hierarchies and even battlefield strategy. Knowing who was older, who was related to whom, and where each clan stood in the broader social structure helped communities function smoothly.

Today, many Kazakhs study their family histories. Traditionally, lineage is traced through the male line, though prominent women are sometimes included. These records preserve names, biographies, legends, and major historical events.

Sabitov said genetic genealogy helps confirm many elements of shezhire.

“In Soviet times, shezhire was treated as mythology. Now we see that, in many cases, it can be scientifically verified. Genetics is a useful tool for checking the accuracy of genealogies,” he said.

He added that, although not every detail is confirmed, most tribal genealogies exhibit strong consistency with genetic data.

“Each tribe has its own history. But genetic genealogy allows us to test how reliable these records are,” Sabitov said.