ASTANA – Economists have studied for decades why some countries struggle to transition from middle-income status to high-income, while some thrive. In a conversation with The Astana Times, World Bank Chief Economist for Central Asia and Europe Ivailo Izvorski explains why it has been hard for countries to escape the middle-income trap and how to break free from it.

Ivailo Izvorski. Photo credit: The Astana Times

Izvorski visited Kazakhstan in February to present the World Development Report 2024, and a companion report, titled Greater Heights: Growing to High Income in Europe and Central Asia.

Recent figures

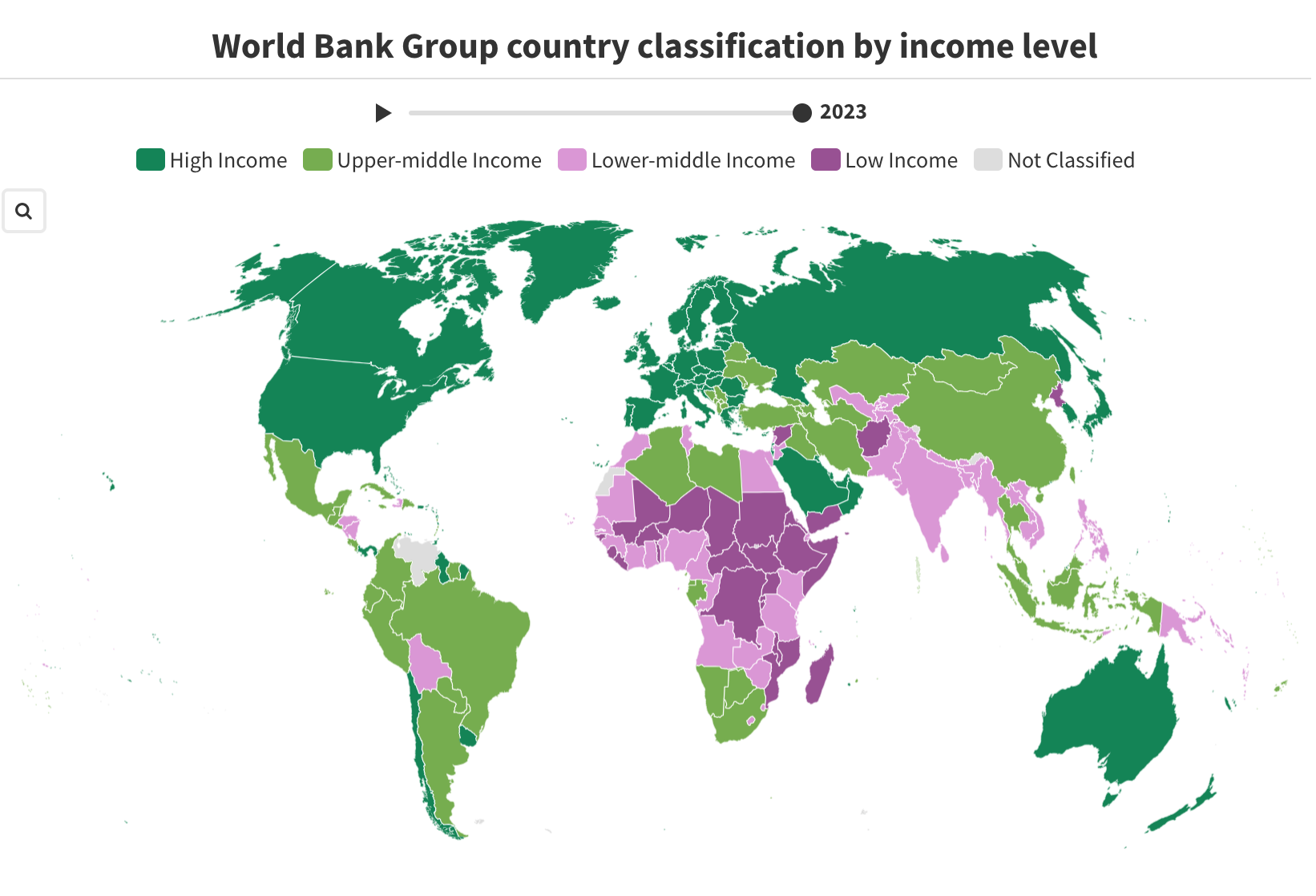

According to the report, 27 countries have reached high-income status since 1990. Ten of these are in Europe and Central Asia and have joined the European Union.

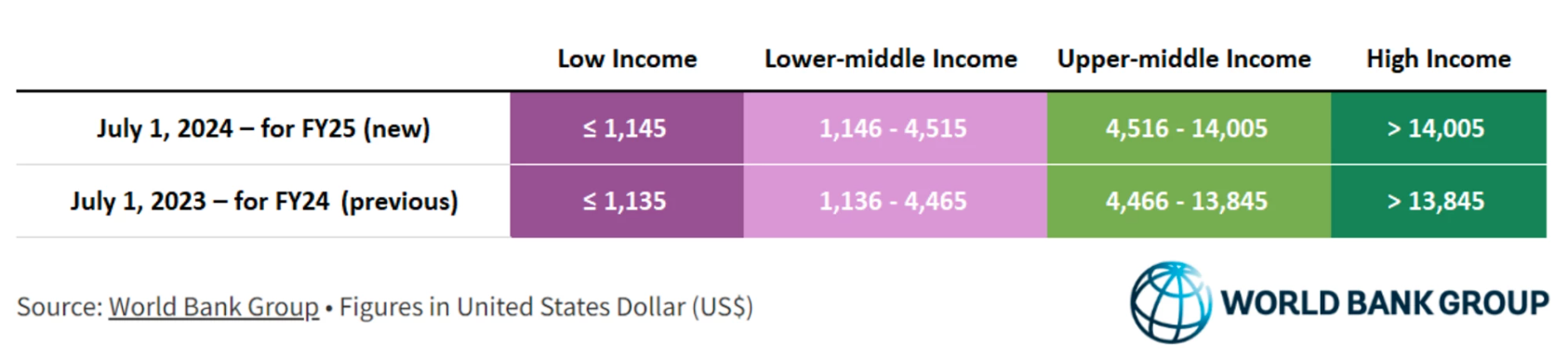

World Bank defines high-income status as reaching the gross national income per capita of at least $14,005, a figure adjusted regularly for inflation.

The World Bank Group assigns the world’s economies to four income groups: low, lower-middle, upper-middle, and high. Photo credit: World Bank

Another 20 countries in Europe and Central Asia have been prosperous since the 1990s. However, that growth has been delayed, leaving them stuck in what economists call the middle-income trap. Among the factors is a slow pace of domestic structural reforms, including a large share of state-owned enterprises and limited competition.

For some countries, except for Turkiye and Central Asia, falling birth rates and a rapid aging population made things worse.

Why is this happening?

“The reason for that slowdown in growth and middle-income trap (…) is that it becomes more complicated to change economic structures, to change policies. The more advanced you become, the more complicated these economic structures are. The policies that took you from low income to middle-income – invest more, make sure all kids go to school – these policies are not the ones to make you high-income. Your economy has to be much more efficient, much more complicated, much more complex,” said Izvorski.

The Astana Times journalist Assel Satubaldina and Ivailo Izvorski during the interview. Photo credit: The Astana Times

The issue here is not just the amount of investment, rather the efficiency and productivity.

Measured in purchasing power parity, enterprises in middle-income countries in Europe and Central Asia have 71% of the human and physical capital per worker that the United States does, yet their GDP per capita is just 38% of the U.S. level. In high-income countries in the region, capital use is 80% of the U.S. level.

“And the reason is that productivity and efficiency are not good. So there’s a lot of inefficiencies, using capital, using labor, using energy,” he said. “For example, in Kazakhstan, per unit of outputs, enterprises use four times more energy than the countries of the European Union. For Europe and Central Asia, this is about two and a half to three times. I mean, imagine what a big difference.”

What’s the path ahead?

Referring to the report, Izvorski said there are two key transitions that middle-income countries need to navigate to become high-income ones, drawing from the experience of those countries that succeeded this transition.

One is from investment to infusion, which entails adopting new technologies, ideas, capital, and expertise from abroad and diffusing them domestically.

The second path is from infusion to innovation – where enterprises do not just accumulate capital, and bring foreign expertise and technology, but also advance innovation. The report highlights this as challenging for most of the middle-income economies in the region.

Where does Kazakhstan stand?

According to Izvorski, Kazakhstan is now transitioning from infusion to innovation.

“It’s getting to a stage where its companies are starting to innovate and to cross the threshold to high-income. More and more enterprises have to be much more innovative. They have to not only bring foreign knowledge, adopt foreign knowledge, but start generating innovations. And innovations are not inventions,” he said.

When asked how long it would take for Kazakhstan to become a high-income country, Izvorski paused for a few seconds. He said that if the country grows by 6-7% a year and considering its current GDP per capita, it may take five to six years.

Kazakhstan is an upper-middle income country. Photo credit: World Bank

The latest figures of 2024, however, report a 4.8% economic growth.

“The government aims to double income per capita by the year 2029, this would require a very dramatic increase in the growth rate, and certainly, if the government succeeds in doubling income per capita by 2029, the country would definitely become high income by then,” he said.

Role of ‘creative destruction’

Central to this transition is the process of creative destruction, a concept introduced by Austrian economist Joseph Alois Schumpeter. Izvorski explains this term as a process through which new and more efficient enterprises, habits and arrangements replace outdated ones.

Ideally, three forces – destruction, preservation and creation – should work harmoniously for an economy to thrive. However, creative destruction is out of balance in the middle-income countries of Europe and Central Asia.

In the 1990s, during the transition from planned economies to market economies, the forces of destruction were dominant, tearing down outdated institutions.

Over time, some economies transitioned toward creation, allowing entrepreneurship and competition to drive growth. But now, forces of preservation gain first seat in the region’s middle-income countries. This is reflected in the large firms, mainly state-owned enterprises, showing reluctance to give up their market dominance, and governments often protecting inefficient industries rather than allowing new firms to emerge and replace them.

Three drivers of economic growth

In the latest report, the World Bank identifies enterprises, talent and social mobility, and energy as three fundamental drivers of economic growth.

Discussing social mobility, proxied in the report as an educational mobility, in more detail, Izvorski explained that social mobility is the perception and reality that people are doing better than their parents in key areas such as education and income.

He stressed the strong link between education and economic growth, while not visible immediately from the data.

“In our report we look at education. Are kids born, for example, say 1990, so the last decade of the 20th century, which is the last year for which we have data, are they doing better than their parents in terms of getting more education?’ he said.

The other way to look at social mobility is whether educational achievement is independent of family background.

“If, let’s say, my father had a university education and I have a university education, but if my neighbor’s father did not have university education, and he did not have university education, this is a very strong correlation between the education of parents and education of children,” said Izvorski.

“This is not good. You would want for mobility. You would want there to be less of a relationship between the education of the parents and the children. You want children to have equal opportunities to get a good education compared to their parents,” he said.

Declining social mobility

Izvorski acknowledged declining social mobility in Europe and Central Asia.

“On both of these metrics, whether the education of children is better than that of the parents, and whether, you know, there is a correlation relationship between the education of parents and children, most countries in Europe and Central Asia, unfortunately, there is a declining social mobility measured by education. And the same story goes for Kazakhstan,” he said.

When asked why social mobility is stalling, Izvorski suggested two factors. One is the declining quality of education and the second is the weak meritocracy system.

“Quality of education has been declining. And then people, currently, have other options. They can do other things, and they choose to do different things. Some go abroad and work abroad. Some do something domestically,” he said.

“But it’s also the whole environment, what we call rewarding merit, that is not yet entrenched fully in most of the countries. How important it is to reward hard work and merit rather than say, everybody has a chance to go to university. Everybody should graduate. That shouldn’t be the case,” Izvorski said, mentioning an example of public universities that often let students pass without strong performance, creating an environment where diplomas are bought rather than earned.

What’s next?

However, the outlook for middle-income countries is not entirely bleak. Passing the $14,000 per capita threshold is possible, but only if countries embrace reforms that reduce inefficiencies, improve competition, and fully tap into the potential of the private sector.

“For many of the countries in Europe and Central Asia, the most important thing is to have a changed way of thinking about the private sector. That is to allow the private sector and private enterprises to thrive and grow freely,” said Izvorski, stressing how critical it is to reduce the burden on enterprises and create a level-playing field.

Beyond that, countries also need to address talent misallocation and harness lower energy intensity to transition to net zero emissions to foster productivity growth.

Success stories

Countries that succeeded in transitioning to high-income countries, such as Estonia, the Czech Republic, and Poland, did so with strong political will, determination, and a clear vision of progress.

“They went very decisively to change their market institutions, went very decisively on the path of market economy, protecting property rights, disciplining state-owned enterprises, privatizing a lot of them, and making sure that these incumbents – enterprises that have leading positions in the country – do not interfere when smaller companies, young companies who want to enter the market,” Izvorski explained.

A key factor in their success stories was a deep integration with the global economy, particularly the EU.

For a complete conversation, follow the link to the YouTube channel of The Astana Times.