The global environmental community is preparing for the 29th Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which will take place in Baku this November.

Photo credit: Shutterstock

As a responsible participant in the global fight against climate change, Kazakhstan is also getting ready for this significant event, where several agreements, including climate financing, are expected to be signed. The country intends to actively engage in all conference activities. In his address, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev identified climate change as one of the key global challenges and called on businesses to adopt cutting-edge technologies in this area and establish a modern emissions monitoring system.

Bakhyt Yessekina.

Since ratifying the Paris Agreement in 2016, Kazakhstan has been adapting advanced international practices in combating climate change. In 2023, a presidential decree approved a strategy for achieving carbon neutrality by 2060, setting priorities for transitioning to a low-carbon development model. Additionally, a government resolution approved the nationally determined contribution (NDC), which targets an unconditional reduction in greenhouse gas emissions of 15%, and 25% with international support, by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. These documents establish the legal framework for Kazakhstan’s current climate policy.

Kazakhstan’s primary legislative document for achieving climate goals and implementing environmental policies is the Environmental Code, which was revised in 2021. The new edition introduces innovative mechanisms to green the economy, such as Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEA) for development programs, the adoption of Best Available Techniques (BAT), and other measures inspired by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) practices. However, certain provisions, especially those concerning CO2 emissions, still need improvement. This includes modernizing the quota system, implementing offset projects, and enhancing the emissions trading system (ETS), which has been in place since 2013.

Article 20 of the Environmental Code identifies the economic sectors subject to quotas, including the power, oil and gas, mining, metallurgy, chemicals, and partially the manufacturing sectors. These regulated sectors are the primary beneficiaries of improved climate legislation, particularly concerning free quotas and participation in domestic carbon trading. In contrast, European countries emphasize a fundamental principle of carbon trading—creating incentives for businesses to reduce emissions and making emission reduction projects profitable. Unfortunately, Kazakhstan’s ETS, which covers only six major sectors and has a surplus of free quotas, does not sufficiently incentivize companies to cut emissions. Meanwhile, sectors such as agriculture, transport, and construction, which account for over 60% of emissions, are not included in the National Carbon Units Plan and do not participate in Kazakhstan’s ETS.

Moreover, Kazakhstan’s approach to calculating quotas is not optimal compared to OECD countries. In Kazakhstan, quotas are based on acceptable limits for the entire country, which are gradually reduced annually. Quotas are then allocated to companies emitting over 20,000 tons of CO2 equivalent annually. This approach relies on historical data, whereas OECD countries set quotas based on the Best Available Techniques (BAT), motivating companies to improve production processes instead of merely penalizing excess emissions. While Kazakhstan’s legislation does include BAT principles, they have not yet been fully implemented. If the new measures in the Environmental Code are put into practice, they could significantly enhance the quota system and ETS.

Kazakhstan’s approach to accountability for environmental violations also differs from OECD standards. The Environmental Code sets penalties based on exceeding emission limits, regardless of the actual harm caused, while OECD countries calculate fines based on the environmental damage inflicted, requiring more substantial evidence of harm. Thus, a more rigorous evidence base for the damage caused by enterprises is required, and the predetermined standard ceases to be the sole benchmark for companies with the potential to pollute the environment.

A similar principle applies to emissions trading, where revenue from ETS is typically directed to the state budget. The OECD, however, recommends reinvesting these funds directly into reducing and preventing emissions, ensuring that the system’s original purpose is maintained.

Other aspects of Kazakhstan’s ETS could also benefit from legislative improvements, such as expanding the coverage of regulated sectors. Currently, less than half of emissions are included in the ETS, which is significantly lower than the European system’s scope. The ETS also requires stricter regulation and greater transparency to facilitate oversight and attract investors.

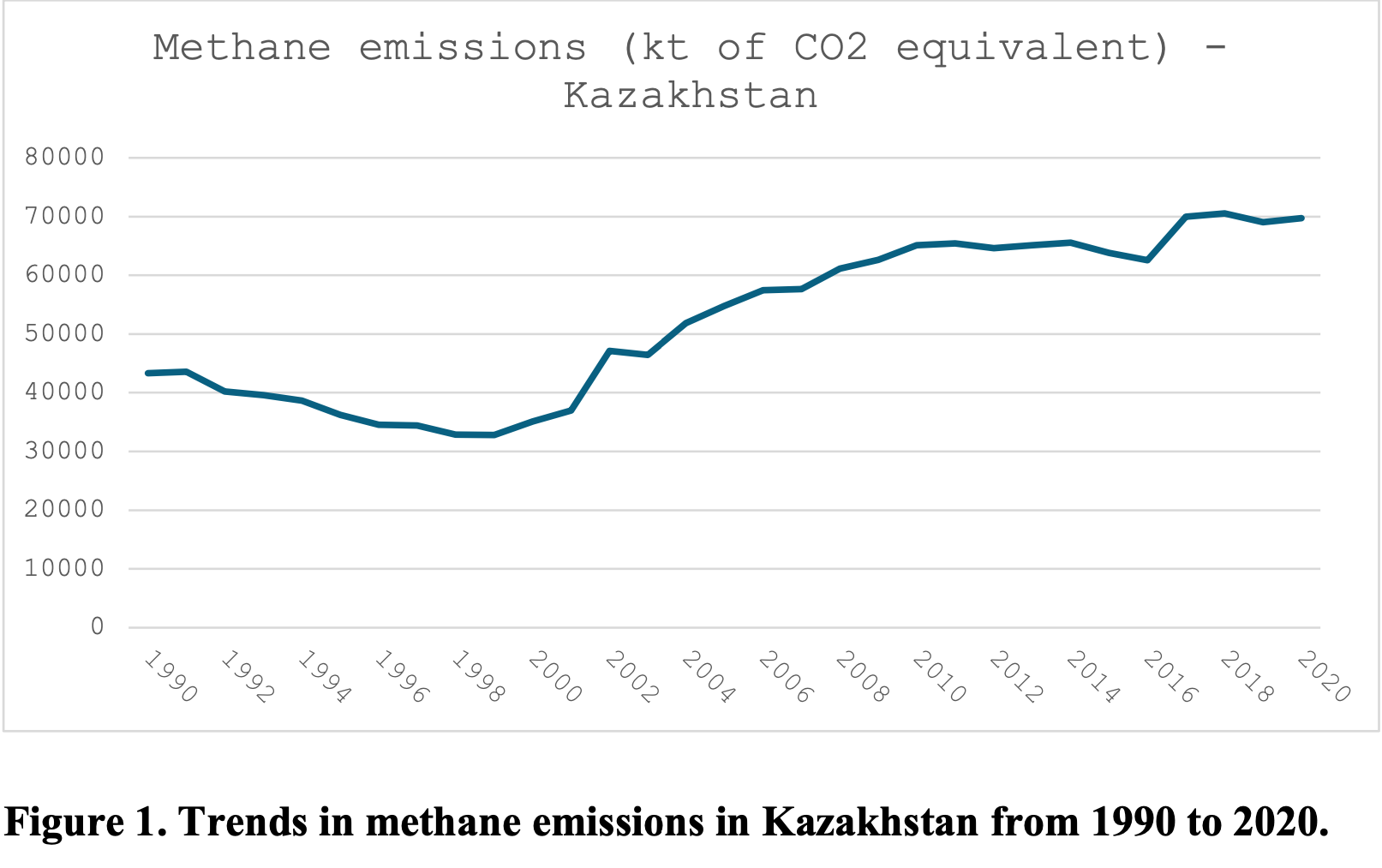

Another way to expand the ETS and fully realize its potential is by including methane emissions, which have been rising steadily since 1999. This would establish a market-based approach to regulating methane emissions and encourage major emitters to reduce them.

This area is particularly relevant following Kazakhstan’s recent accession to the Global Methane Pledge, which aims to set specific methane reduction targets. There is limited international experience in methane market regulation outside of EU initiatives, presenting Kazakhstan with an opportunity to become a leader in implementing this approach.

Offset projects offer a promising path for reducing overall emissions by compensating for them through additional greenhouse gas absorption. Kazakhstan, like OECD countries, uses this concept to attract investment in environmental projects, allowing offset units to be sold on the market via ETS while reducing overall emissions. However, offsetting faces common challenges, such as verifying the quality of offset units. Standards need to be tightened to ensure compliance with the additionality principle, meaning that offsets should result from intentional absorption actions rather than existing activities. There are also issues such as double counting, inaccuracies in calculating absorption due to complex methodologies, and the inability to use certain absorption sources, like pastures, for offset projects.

However, addressing these challenges requires the development and implementation of new standards, including requirements for the qualification of experts in validation and verification. A draft has already been developed by experts from the Green Academy, with the support of the EBRD, and is awaiting approval from the relevant government authorities.

The author is Dr. Bakhyt Yessekina, the member of the Green Economy Council under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Director of the Scientific -Educational Center Green Academy.