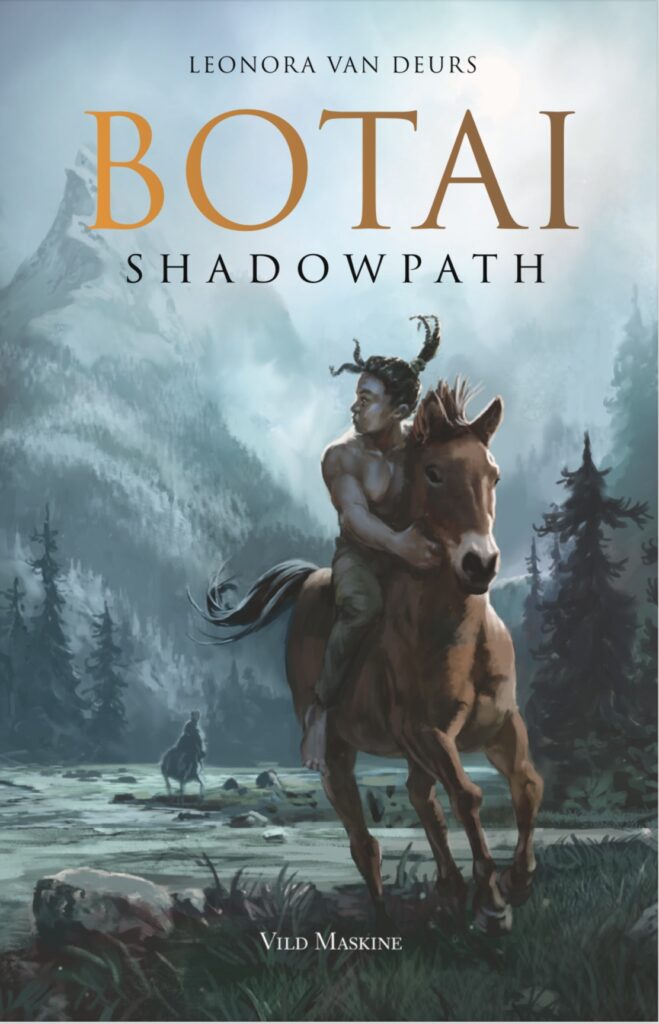

ASTANA – Danish author Leonora van Deurs’s historical fantasy novel “Botai – Shadowpath” based on Kazakhstan’s Botai culture of first horse breeders is a unique piece that bridges the present and past, science and fiction, and Danish and Kazakh cultures. Following its debut in Copenhagen in January, the author visited Kazakhstan, the land where the Botai people once roamed.

Leonora van Deurs was 15 when she first started writing the book. Photo from her instagram account @leonora.van.deurs

In an interview with The Astana Times, she shared her inspiration and journey for the book, her approach to balancing science with creativity, and the first glimpse into the second book that she is working on.

Her book transports a reader to the world of Botai culture, little known in the rest of the world. Dating back to approximately 3700–3100 B.C.E, the Botai people were among the earliest, if not the first, to domesticate horses. The presence of horse bones, bridles, and residues of fermented mare’s milk in pottery suggests they used horses for riding, marking a significant advancement in human-animal relationships.

The inspiration behind the book

The idea for the story behind “Botai – Shadowpath” began with van Deurs watching a documentary “Equus: The Story of the Horse,” which was about the evolution of the relationship between man and horse in Botai culture, living 5,500 years ago in what is now northern Kazakhstan.

In 2015-2016, a team of scientists from the geogenetics center at the University of Copenhagen conducted a scientific study looking into the ancient steppe genomes. The result was an article published in the Nature journal titled “137 Ancient Human Genomes from Across the Eurasian Steppes.”

English translation of around first 40 pages of the story is made by Paul Russel Garrett. Kazakh translation is also to be published.

Nurbol Baimukhanov, co-producer of “Equus: The Story of the Horse,” was also involved in the project and decided to turn it into a film with a complete reconstruction of the eneolithic era within the Botai culture.

After discovering the documentary, van Deurs became passionate about the story. It enriched her imagination, leading to the fantasy take on Botai’s history.

“The film takes you through the different phases from the beginning of the domestication of the horse, which happened here in Botai, in Kazakhstan. It’s very beautiful images. I think hearing from the scientists that are interviewed, hearing from geneticists, and also seeing the reconstruction of the Botai site was extremely inspiring. I thought this was such a beautiful story. I was surprised that no one knew about the story. So I thought I would try and use my skill within writing novels to get this story to be known to the public,” said van Deurs.

The plot of the fantasy novel follows three young people who set off on a journey that will change their fates. Lyez and Jalgi, who grew up in Botai on the Eurasian steppe, live in harmony with nature and horses until a curse, known as Minwri, brings illness and death. Determined to save his people, Jalgi embarks on a dangerous journey to the Altai Mountains in search of the shining stones that can break the curse. Meanwhile, Nakou, a Yamnaya nomad who lost her family to the curse, is forced to flee to the Altai Mountains, where she faces an unwanted marriage.

Balancing history and fiction, science and creativity

“Botai – Shadowpath” is a remarkable feat of history and imagination. “My book, I think, is the perfect example of science working with fiction and with a more creative subject, such as writing and literature,” said van Deurs.

Botai-Burabai open-air ethno-museum shows the reconstruction of the housing allocation of Botai people. Photo credit: borovoe. kz

History and science could be useful in putting one’s life and culture in context. But if we want to make the history easier to digest, we turn to art. For many readers, a historical fiction novel might be the point of entry into the world of history or a window into a particular culture and period.

“I couldn’t have written this book without the science and if it hadn’t been for the literature part, then people wouldn’t have been interested. The problem with science is that it’s a little difficult to access for other people who may not work in science. I think if you can manage to make them complement each other, this is truly a very good thing,” she added.

While approaching the writing, van Deurs wasn’t after quick results. She has done meticulous research about the Botai culture as she strived to fill in the gaps in her knowledge.

“The first year I didn’t write that productively, I was mostly researching, and I was working with the [Eske] Willerslev’s [a Danish evolutionary geneticist] team at the center of geo genetics in Copenhagen, and they were helping me by sending me scientific articles that I could read. I had a lot of questions at the time, of course, and I was figuring out what elements to include from history, and they were really helpful,” said van Deurs.

After the first year, she spent another two writing the novel, which debuted in January.

The way van Deurs speaks about her writing is in direct contact with her current study of mathematics and physics at the University of Münster in Germany.

“The process of writing for me is a little bit more, shall we say, flowy than for other authors. I think I’m naturally structured. I study mathematical physics as well, so it’s quite a structured way of thinking, which, at the same time, allows for creativity,” she said.

Perhaps her mathematical skills also played a role in her creative process.

“Science, for me, is like a condition. It’s something I have to do. From a very young age I wanted to be a scientist, but then I also knew that I really loved to write and I really love to do creative things. I also play jazz piano, for example, and I do other creative things,” said van Deurs.

“I think the way we view it today is people like to label themselves: like I am a mathematician, or I am an author. I like to not label myself as much. Of course, it depends on the context, but you can be both. I think once I do one thing, it’s just a break from the other and doing both actually balances me as a person,” she added.

‘Is the context of the story true?’ readers might inevitably ask about historical fiction. There is a fine line between history and fiction – a balance van Deurs has mastered admirably in her book. For those inquiring, van Deurs included a postscript with an explanation of the Botai culture and history that inspired her novel.

“The reason I put it in the back [of the book] is because I want people to first read the story and then get really invested and engaged, hopefully, in the subject by reading about it and really living the Bronze Age and living the history of Botai. And then, when they have really gained an interest in it, they can turn to the postscript,” said van Deurs.

Despite being set in an actual Botai culture environment, her novel is not an attempt to recreate the past, but rather bring a leap of imagination into the context of Botai people. She aimed to make readers drawn to the story first before throwing a lot of scientific facts that could be off-putting.

“It’s like a bit of a strategic way for me to get people to read about it, because young people have a short attention span. We just have to admit that. Especially now, with social media being so fast-paced, like TikTok, people’s attention span is extremely short. And this goes for fiction as well. Like you have to have a very fast-paced plot,” she added.

The environmental and cultural message

With the universal theme of people and nature running through her work, it is no surprise that it serves as a powerful reminder of the environmental importance of that bond.

“I think one message of my book is that, definitely, today, I think we’ve really lost contact with nature. (…) And when you lose contact with nature, unfortunately, we also lose our empathy for nature. We’re in a biodiversity and climate crisis. The more connection we have with nature, the better we understand our past, the Bronze Age, for example, and the better we can take care and empathize with the problems that we have with nature today,” said van Deurs.

“Hopefully, when you see it from the perspective of these Bronze Age people in Botai, you will see how strongly they feel for nature. You’ll hopefully feel the connection to the Kazakh nature as well,” she added.

For Kazakhs, literature might also become one of the good means of telling their cultural story.

“For a Kazakh person, I hope when they read it, they will really live the cultural history of the country. I think you can do that for any culture. And I think this is very healthy in strengthening our cultural connections between countries,” said van Deurs.

“Botai – Shadowpath” is written in Danish, with the first 40 pages already translated into English. The book will also receive funding for the Kazakh translation.

Visit to Kazakhstan

Van Deurs described her visits to Kazakhstan as “surreal.” “It was quite surreal to stand in the museum and see some of the artifacts that are literally in my book,” she said.

Some of the them include arrows, scrapers, stone grinders, and other tools. “So there was an amulet, for example, that is used at the end of my book. It’s a little rock with a hole in it,” she added.

Van Deurs also plans to explore nature and go horseback riding near the Almaty and Altai Mountains in the East Kazakhstan Region.

“I can’t speak for the experiences I will have in the future here in our journey around Kazakhstan. I have not really been to Kazakh nature yet, but I think it will be a big moment for me to see where the Botai people lived, which is something that I’ve had to imagine and research from my home country in Denmark. Standing there and smelling it, feeling it and sensing nature will be a really big moment for me,” said van Deurs.

She is working on the second book of “Botai – Shadowpath” and hopes that her journey through Kazakhstan will inspire her to write a fitting continuation of the Botai people’s story.

“My second book is in the same world as the first book, but it’s a few years after the first book, so some of my characters have grown a little bit older, which adds an extra dimension to their way of thinking, their way of acting in this environment. It will also focus a little bit more on the other steppe cultures that were around, aside from the Botai people,” said van Deurs, giving a sneak-peak into the second book.