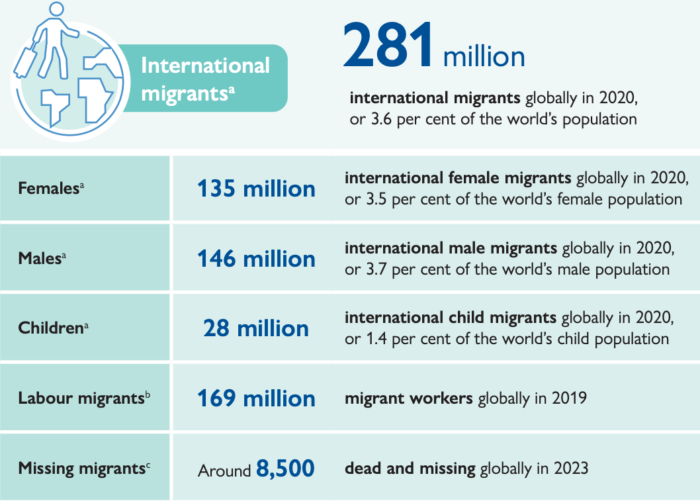

ASTANA—The latest data from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) indicate nearly 281 million international migrants worldwide or 3.6% of the global population. In an interview with The Astana Times, Caress Schenk, an associate professor of political science at Astana-based Nazarbayev University, discusses why migration matters, what is an ideal migration policy, and what are the migration trends in Central Asia.

Caress Schenk has research expertise in the politics of immigration and national identity in Eurasia. Photo credit: screenshot from The Astana Times YouTube interview

While there is no universally agreed definition of migration or migrant, the United Nations notes an international migrant can be anyone who has moved from their country of usual residence. This definition includes short-term migrants, who have relocated for a period of at least three months but less than a year, and long-term migrants, who have moved for at least one year.

Schenk said migrants are often a “really easy target.”

“They are seen as something that’s not normal, or they’re seen as something that is not us,” she said. “Because of that, I think migrants can become very vulnerable as a result. Obviously, when we talk about migrants, there are lots of different types of migrants, and people move all over – inside of countries and out from country to country.”

Migration has been a fundamental aspect of human history. Over the ages, people have moved in pursuit of better living conditions, escape conflicts, seek safety, or explore new opportunities.

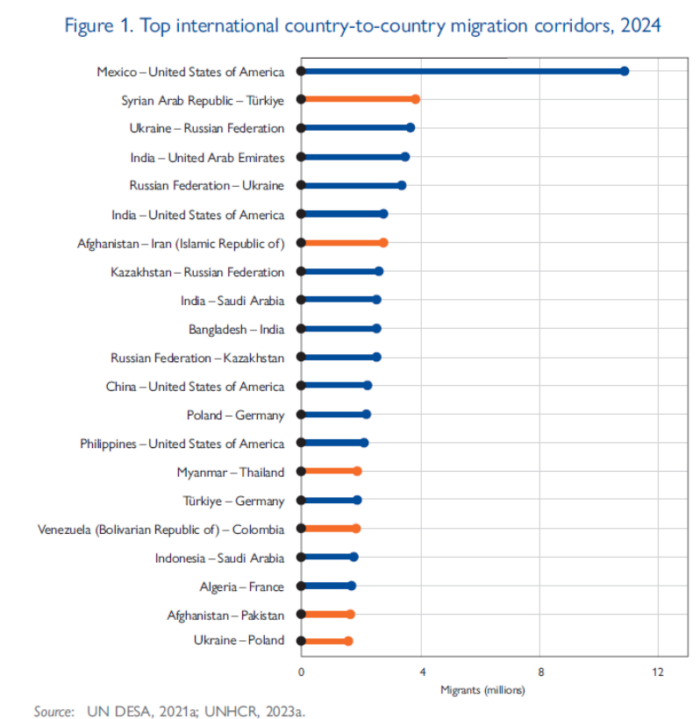

The World Migration Report 2024 says most migration is regular, safe, and orderly, often regionally focused and work-related. It also notes that international migration remains “relatively uncommon.” Headlines tend to spotlight only a fraction of the broader narrative.

Snapshot from the World Migration Report 2024.

However, migration is frequently misrepresented due to misinformation and political agendas, leading to skewed and inaccurate portrayals of its straightforward truths and intricate, context-specific realities.

According to Schenk, one of the biggest challenges is treating migrants as if they are different, which she believes dehumanizes them. It sends a message that they do not deserve full rights or the ability to work. They are often excluded from the healthcare system.

“I think that those kinds of xenophobic tendencies or impulses are really dangerous because it is a very slippery slope to say, ‘well, we want to protect jobs for our citizens,’ to dehumanizing migrants in all sorts of ways that leads to violence, whether it is outright violence or other types of more subtle violence,” said the professor.

Schenk believes people have much more in common with each other as humans rather than “arbitrary artificial borders and boundaries on a map would give in terms of identity.

Economic implications

According to IOM, migration drives human development and can benefit migrants, their families, and their countries of origin.

Migrants can earn wages abroad that are many times higher than what they could earn doing similar jobs at home. According to the organization’s data, international remittances rose from $128 billion in 2000 to $831 billion in 2022.

Migration can also enhance the skill base, crucial for destination countries facing population declines. It can also increase the labor supply in sectors and occupations with worker shortages and address job market mismatches.

Professor Schenk noted that the research on the economic impact of migrants is divided.

“I was just having a conversation with some colleagues about the economic impact of migrants the other day. They wanted to make the argument that migrants take jobs and they are bad for the economy. I wanted to make the opposite argument, that migrants are good for the economy, they bring vitality to the economy, and diversity to society,” she said.

She noted that the truth is that one can find evidence to support either viewpoint because the research is so diverse.

“It demonstrates a lot of different things about complex human systems. (…) I think that in many ways, migrants can be quite good for society, but depending on how people react to those migrants, it can create a lot of really negative outcomes,” she added.

Migration trends in Kazakhstan

According to the Bureau of National Statistics, in 2023, 25,387 people arrived in Kazakhstan for permanent residence, and 16,094 people left the country. The number of arrivals in Kazakhstan increased by 45.7% compared to 2022, while the number of persons leaving the country decreased by 33.3%. Migrants mainly came from the countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States, accounting for 86.3% of arrivals.

Kazakhstan has witnessed a significant shift in migration patterns in recent years, influenced by various geopolitical events.

Schenk shed light on these changes. The economic instability in Russia from 2008 to 2010, compounded by its unfriendly policies towards migrants, has driven many from Central Asia to seek opportunities in Kazakhstan.

“When things weren’t so good in Russia, or sometimes when Russia was making policies that were really migrant unfriendly, it made it really hard for migrants to stay in Russia. We started to see more migrants coming and trying to find work in Kazakhstan. This would be migrants from Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, but we always have seen those migrants come because there is just general openness among Central Asian countries, and it is normal to work across those boundaries,” she explained.

The mobilization efforts in Russia also led to a significant influx of Russian citizens into Kazakhstan.

“There were hundreds of thousands of Russian men, mostly, but also families that came into Kazakhstan within a really short period of time,” she added, highlighting that such a vast influx immediately sent demand in the real estate market up, with pricing substantially rising.

In addition to these migration trends, Schenk also mentioned the introduction of a visa-free regime with China.

Schenk commended Kazakhstan’s ability to navigate these complex dynamics.

“[There is] the idea that Kazakhstan has limited choices because we are right between Russia and China. I don’t think that actually gives Kazakhstan the credit that it has due because it is quite adept at maneuvering and adapting to all of the different things that are going on around it and doing things in the country that matter a lot for the people in the country that has nothing to do with what is going on outside,” she said.

Is there an ideal migration policy?

Highlighting the inherent value migrants bring to society, Schenk advocates for a more open and inclusive approach.

“My ideal migration policy would be to say just let everybody in who wants to come in. Let’s not regulate these things because we are all people, and let’s work together towards economic goals, social goals, or what have you,” Schenk said.

Snapshot from the World Migration Report 2024.

This idealistic vision, however, clashes with the current political landscape. “That is not the way the world works. That is not the way the world is set up right now. Even though I think that would be better, it is not very realistic. No policymaker could ever be elected on a platform where they said, let’s throw the gates open, or let’s open all the borders and let everybody in. That would be political suicide,” she explained.

The professor went on to emphasize the counterproductive nature of strict migration controls.

“There is a sort of law of migration that the more you try to control migrants, the less control you will actually have. It is like child-rearing. The more controlling you are as a parent, the more your child will rebel, and the more they will not flourish and grow to be the person they can be. Same for migration, the more you try to control migrants, the less they will be able to contribute to society, whether it is economically or socially,” she said.

Schenk said migrants bring invaluable perspectives and ideas that enrich host societies. But openness sometimes scares people.

“That openness is really scary for some people, and so the impulse is to control, to close down the spaces that migrants can operate in, and to make it harder for them to live and work and feel free in society. That actually works at cross purposes. It is contrary to the idea of all of the things that migrants can bring to society,” said Schenk.

Drawing from personal experience in academia, she noted migrants bring fresh and interesting ideas about the world.

“At the university where we teach, sometimes we get international students, and I love this because they bring in a different perspective that our local students don’t necessarily have. As an American, I can tell them that there are other perspectives outside of Kazakhstan, but if a classmate is sitting next to them that’s from Nigeria or Turkey or Pakistan and says, ‘In our country, here’s our experience’ – this speaks volumes,” she said.

Political messaging is important

Schenk stressed the important role of political messaging in shaping public perceptions about migration and migrants. Emphasizing the predominantly negative portrayal of migrants in the media, she suggests a shift towards highlighting the positive contributions of migrants to society.

“When we look at the ways that migrants are presented in the press, it is almost uniformly negative. Why does it have to be that way? Well, because it gets votes. People tend to vote for politicians that have a resolute stance on migration,” she explained. “But if we change the narrative to look more at the benefits that migrants bring, people would start to believe that if you tell them the positive sides of this too.”

Schenk said she does not understand heavy reliance on negative messages, pointing out that politicians often resort to fear-mongering instead of providing truthful and informative narratives.

“This truth, it is really complicated, but fear narrows people down to staying in their spaces and acting in limited sorts of ways. But that is really stifling your own population,” she added.

The full interview is available on The Astana Times YouTube channel.