ASTANA – Kazakhstan took over the chairmanship of the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea (IFAS) this year. During its three-year presidency of the IFAS, Kazakhstan will determine the course of the Aral Sea revival. The Zakon.kz news agency published an article examining forthcoming projects facilitated by the IFAS, alongside retrospective assessments of past initiatives executed through the World Bank and other international institutions.

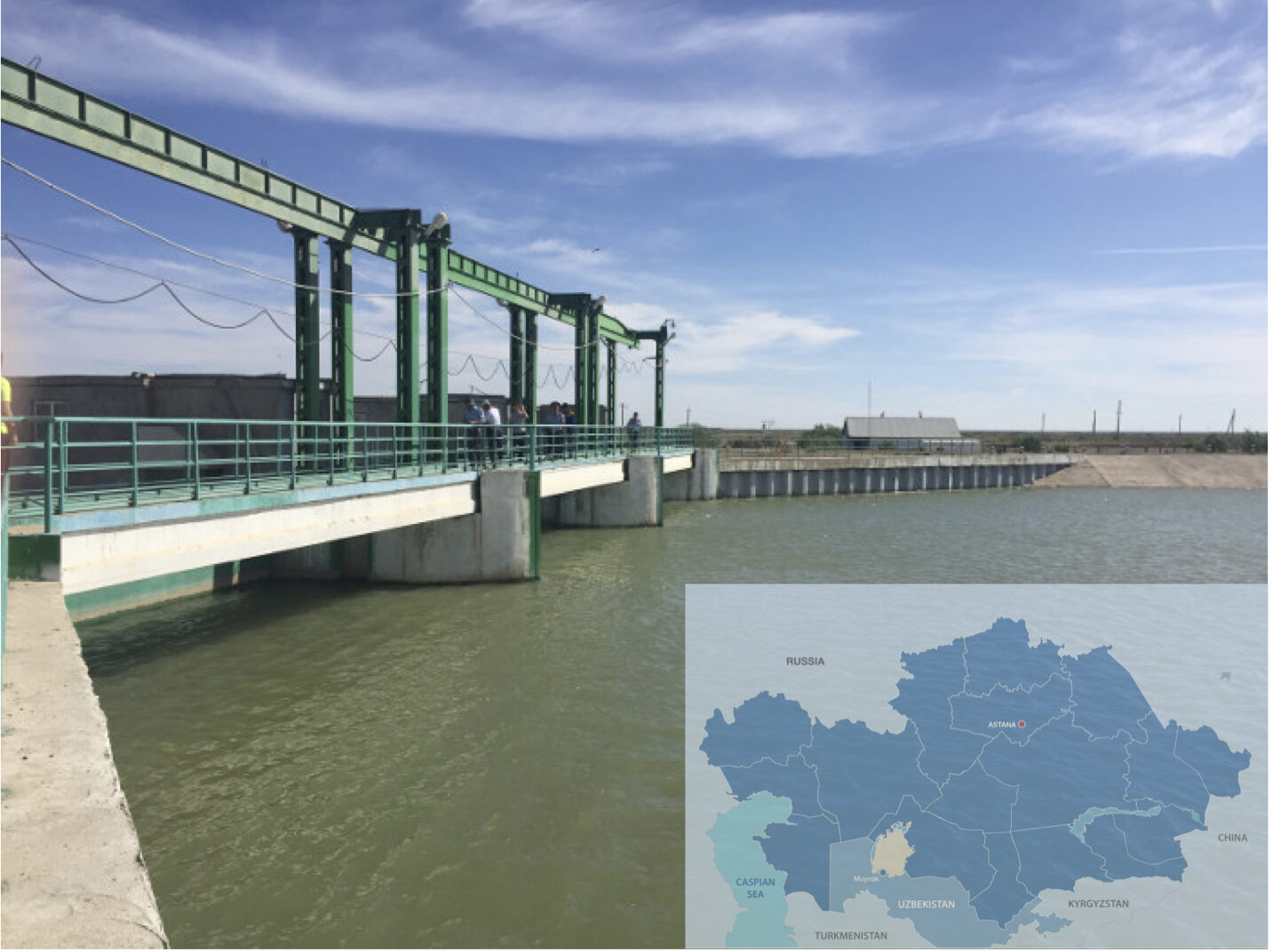

The Kokaral dam built in 2005 ensured the rapid filling of the northern Aral. Photo credit: kazaral.org. Click to see the map in full size.

Saryshyganak project

Through rampant Soviet irrigation projects and over-extraction of water, severe damage was inflicted on the Aral Sea and local communities, leading to a 90% shrinkage.

NASA image of the Aral Sea from 2021. Photo credit: kazaral.org

According to IFAS Acting Executive Director Zauresh Alimbetova, the good news is that there is hope for reversing the decline of both the sea and the region, especially during Kazakhstan’s chairmanship of the IFAS.

The World Bank has been financing the Aral Sea renaissance initiatives since the early 2000s through the Regulation of the Syr Darya River and Preservation of the Northern Aral project, also known as RRSSAM-1. The IFAS played a key role in implementing the project.

The project’s first phase financed the construction of the Kokaral dam in 2005, which ensured the rapid filling of the northern Aral, also known as the Small Aral Sea. The water level in the reservoir reached its design elevation of 42 meters (according to the Baltic system) in one year.

The restoration progress, while still limited, demonstrates the remarkable resilience of the sea. The project’s final goal is to fill the Saryshyganak bay so that the sea reaches the coastal city of Aralsk.

Alimbetova outlined three potential measures.

The first is to gradually fill the sea by raising the level of the Kokaral dam to 48 meters. The second option is to build a 52-meter-high dam in the Saryshyganak bay without altering the Kokaral dam. A supply canal will be constructed either via Lake Kamystybas or Lake Tusshi. The third option proposes to raise the Kokaral dam and build a supply canal from Kokaral to Saryshyganak bay.

The state’s construction expertise will determine which of these options to adopt, according to Alimbetova.

Saksaul plantation project

Among other success stories is Kazakhstan’s saksaul plantation project. Saxaul plantations serve as natural protectors against the wrath of dust storms, especially in deserted areas, dramatically reducing the health hazards arising from the spread of the salt-laden sand containing tons of poisonous particles.

Saxaul plantations serve as natural protectors against dust storms. Photo credit: water-ca.org

In 2022, over 60,000 saksaul seedlings were planted, and the number increased to 110,000 saplings in 2023.

Initially, trucks were used to deliver water to the saxaul fields. Since a well was drilled there last year, it is now possible to increase the area of saxaul, grow other succulent plants, and irrigate cattle and other wild animals.

“For the first time in 2023, we grew saxaul using hydrogel and a closed root system methodology. The rooting rate was up to 60%,” said Alimbetova.

“Saxaul has become the desert’s savior, so we must continue planting it, especially in the Aral Sea area, which has dried up and left behind several million hectares of salted land. Kazakhstan’s presidential administration has proposed planting 1.1 million hectares of saxaul between 2021 and 2025,” said Alimbetova.

The neighboring country, Uzbekistan, also initiated a saxaul plantation project in 2018. They cultivated over 1.73 million hectares of forest plantations in the Aralkum desert.

According to Alimbetova, to grow seedlings, a forest nursery with a laboratory and a research station was built in Kazalinsk city in the Kyzylorda Region under the World Bank’s program.

To preserve the remaining biodiversity, the Center for Adaptation of Wild Animals to Climate Change was created. Situated on the Small Aral, spanning 47,000 hectares, it includes a designated area for observing both animals and plants. The region was once home to 38 species of fish and rare animals.

Aral Sea fishing history

Villages and their inhabitants were impacted by the devastating consequences of the drying sea the most. For the people of Karateren village, located 40 kilometers from the Aral Sea, the thought of the sea disappearing was once unthinkable.

“Fishing has been practiced in our village for over a century. During those years and up to the 1980s, there were no problems with fish because the Aral Sea had enough water and fishermen always returned with full loads of catch,” said the village akim (mayor) Berikbol Makhanov to Zakon.kz.

“There were 4,000 people living here, [there were] advanced brigades, dynasties of fishermen, fish factories, and a plastic boat factory. The auyl [village in Kazakh] was prosperous in those years. Due to a shortage of water in the 1980s, fishermen started to relocate and work in fishing brigades in nearby districts like Balkhash and Zaisan,” he explained.

Local restoration projects

Even as the sea bed dried out, former residents have not lost all hope of returning the life-giving, serene water that the Aral Sea once offered.

Akshabak Batimova is one of those hereditary fisherwomen from the Kyzylorda Region. She was born in the Mergensai fishing village of the Aral district. Following the example of her father and grandfather, she dedicated her life to the sea, studying to become a technologist in fish production.

“Over 10,000 villagers during those years were involved in fishing. We had 22 fishing collective farms. But in the early 1990s, the sea began to dry up rapidly, which left the people without work as the water turned completely salty and the fish disappeared. Desperate, the locals abandoned their auyls and either moved to Balkhash to continue fishing or started a new life in other regions of the republic,” said Batimova.

However, some villagers refused to give up the fight.

“There were also those who survived in their native land. My family didn’t go anywhere, and we started looking for partners to revive the fishery. In August 1996, we found partners in Denmark and went there,” she added.

The result was the project called ‘From Kattegat to Aral,’ which helped Aral and Danish fishers to catch and process flounder in Tastybek village.

“We united around 1,000 fishermen and worked closely with the Danish fishermen’s society ‘Living Sea.’ As part of the ‘From Kattegat to Aral project,’ the Danes allocated us money for boats, gear, and all necessary equipment. We bought the former bakery building and transformed it into a ‘Flounder-fish’ production center,” said Batimova.

According to her, after the first phase of the RRSSAM-1 project, the salinity of the sea decreased from 32 grams to 17 grams per liter of water, the fishing industry was revived and 50,000 hectares of pastures were restored.

The villagers hold on to the hope that with Kazakhstan’s engagement and leadership at IFAS, the sea might one day return closer to the former Aralsk shore.