ASTANA – The beginning of the second decade of the 2000s marked the turning point for Kazakh auteur cinema. The country launched a reboot of Kazakh art cinema through Kazakhfilm studios, which became the catalyst for realizing Kazakh directors’ unique points of view.

Photo credit: Shutterstock.

With a lineup of films at the Cannes, Berlin, and Venice Film Festivals by then-young filmmakers Emir Baigazin, Adilkhan Yerzhanov, and Farhat Sharipov (alumnus of the Temirbek Zhurgenov Kazakh National Academy of Arts), world critics started noticing the phenomena of Kazakhs auteur cinema.

Emir Baigazin

A native of the Aktobe Region, Baigazin was born in 1984. It took him a few years to pursue directing full-time. After studying for only a year at a university in Aktobe, Baigazin worked for two years as an actor at the region’s drama theater. At age 20, he enrolled in Kazakh National Arts Academy to become an actor, ultimately choosing film directing as his major.

Emir Baigazin. Photo credit: Baizagin’s Facebook page.

In 2013, Emir Baigazin became the first Kazakh director to participate in the main competition of the International Berlin Film Festival with his debut feature film “Harmony Lessons.” Baigazin’s competitors at the time included prominent directors Steven Soderbergh, Gus Van Sant and Bruno Dumont.

The film about bullying in a rural school received the Silver Bear for outstanding artistic achievement in Berlin that year and the main prize at the 18th Sarajevo International Film Festival, as well as almost a dozen Grand Prix at various film festivals.

In 2013, Hollywood Reporter wrote that the film is “grimly poetic, formally disciplined and psychologically gripping, this is a legitimate discovery.” According to critics, the Berlinale programmers’ bold decision to usher Kazakh writer-director Emir Baigazin into the big league with “Harmony Lessons” paid off.

In 2013, Baigazin became the first Kazakh director to participate in the main competition of the International Berlin Film Festival with his film “Harmony Lessons.” Photo credit: Kinopoisk.

“What also makes ‘Harmony Lessons’ fascinating is weighing the familiarity of certain thematic elements against the unusual setting and approach. Essentially, the film is about the process of ostracism, humiliation and bullying by which smart teenage kids can be transformed in the cruel environment of high school into marginalized figures capable of violence. There are vague echoes of films like Gus Van Sant’s ‘Elephant’ in the juxtaposition of brutality and lyricism, but this is very much the culturally specific work of a distinctive voice,” reads the review.

The main character’s story of bullying and internalized emotional turmoil parallels situations at schools across America and worldwide. The main character is inevitably denied a happy ending, but the finale becomes more troubling, even haunting, as the Hollywood reporter called it.

“Harmony Lessons” became part of Baigazin’s coming-of-age trilogy, in which the primary protagonists are youngsters and teenagers who act as lone wolves, opposing adults and each other. The trilogy’s second installment, “The Wounded Angel,” premiered at the International Berlin Film Festival in 2016. The film received the Best Film award at the Funf Seen Filmfest in Germany, Special Jury Prize at the Jeju Film Festival in South Korea, and Best Director at the Art Film Fest in Kosice (Slovakia).

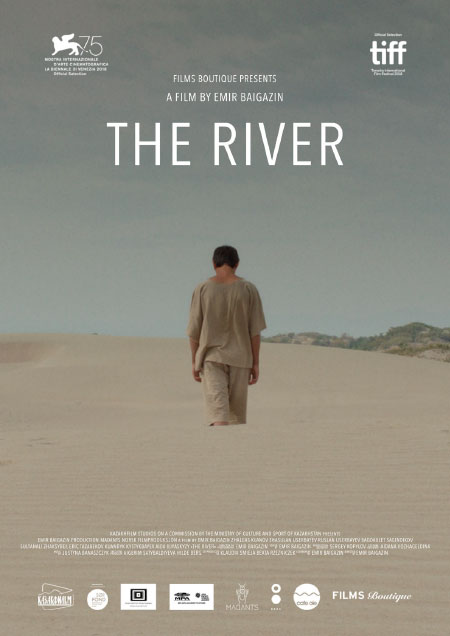

“The River,” the concluding installment of the trilogy, was awarded best directing in Venice in the competition of experimental and new films “Horizons” (2018). Photo credit: Kinopoisk.

“The River,” the concluding installment of the trilogy, was awarded best directing in Venice in the Horizons competition of experimental and new films (2018) and a resident grant from the Hollywood Foreign Press Association.

According to Hollywood Reporter, “The Wounded Angel” is transfixing even when perplexing, making every frame a composition of austere beauty. Baigazin, according to the critics, has developed into an even more assured visual stylist, with minimal camera movement and action predominantly playing out within static shots.

Describing his process in an interview with The Village, Emir Baigazin said that for him, it is important to have an “inner wall” of the film.

“I include only what I consider necessary in the film, frustrating my crew by cutting much of what we have filmed. To me, there is real beauty and candy-box beauty. If, during the editing, you keep a cold heart and think about the film’s internal, invisible development, then you achieve the first. Then the film scenes ‘burn out’ the screen and catch the eye,” he said.

Adilkhan Yerzhanov

Adilkhan Yerzhanov was born in Zhezkazgan in 1982. A Kazakh National Academy of Arts graduate, Yerzhanov is perhaps the most prolific master of Kazakh arthouse. In 2022, he launched five projects. His films have appeared in the programs of prominent festivals in Cannes (“Owners,” “Affectionate Indifference of the World”), Venice (“Yellow Cat,” “Goliath”), San Sebastian (“A Dark, Dark Man”) and Rotterdam (“Storm”).

Adilkhan Yerzhanov. Photo credit: esquire.kz

As a child, he was fascinated with drawing comics, which later translated into his directorial style. According to the critics, his works are a type of film comic in which catchy amateur theater scenography coexists with ridiculous comedy and piercing social critique. He targets patriarchal foundations, a meaningless tradition covering corruption and lawlessness in provincial life. The action of practically all films takes place in the same author’s universe – the village of Karatas, which is easy to visit but difficult to get out.

“As a kid, I wanted to make cartoons, even though I wasn’t good at drawing. I had no idea how to make cartoons and had to do everything frame by frame. My enthusiasm gradually evolved into sketching comics, but I lacked access to new publications. I only recall receiving a few editions of Murzilka magazine. This Soviet comics method is most likely reflected in my storyboards, which I create as if they were my children’s comics,” Yerzhanov said in one of his interviews.

According to the critics, the quintessence of Yerzhanov’s auteur style was a black comedy, “A Dark, Dark Man,” about the search for a serial killer in a provincial village. The horror of social realism is softened by absurdist and graveyard humor. The action occurs in three locations – a picturesque cornfield, a warehouse with cargo containers, where a child’s corpse is found, and a police station.

According to the critics, the quintessence of Yerzhanov’s auteur style was a black comedy “A Dark, Dark Man.” Photo credit: Kinopoisk.

The New York Times critics described the film as “clearly designed for big-screen immersion,” putting it on the same level for its methods and themes with such acclaimed art-house titles as Bruno Dumont’s “Humanité,” Bong Joon Ho’s “Memories of Murder” and Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s “Once Upon a Time in Anatolia.”

“The mystery aspect is handled obliquely. The film is more of a mood piece, and much of its pitch-black humor derives from the contrast between the barren landscape and the sheer number of horrors it contains. … Only the closing moments seem less nervy,” the review reads.

Its obvious hopelessness creates space for hope. Because one of the most powerful manifestations of hope occurs when everything around you is adverse, and there is no ground for this hope to exist. The main character, Bekzat, played by Daniyar Alshinov, discovers that when he has nothing and there are no more expectations from life, in that very moment he decides to do things differently for the first time.

Farkhat Sharipov

Native of Almaty, Sharipov was born in 1983. He became a director by chance. As Sharipov said in his interviews, in his teen years, he was a musician and a member of a rock band. His initial dream was to become a sound engineer. However, upon enrolling at the Kazakh National Academy of Arts, he walked into the wrong door and applied for directing instead of sound engineering. Eventually, he completed both majors at the academy.

Farkhat Sharipov. Photo credti: RIA news.

He made his cinematic debut in 2010 with “The Tale of the Pink Hare.” According to critics, the story of student Yerlan, who gets to attend parties, from bohemian to gangster, meet, quarrel, and make peace with a charming rich girl, marked the end of the glamor movie era in Kazakhstan’s film industry.

Sharipov’s new protagonist is an ordinary man in his 40s going through a midlife crisis in “The Secret of a Leader” (2018). The film opened with a direct quote from Rashid Nugmanov’s “The Needle” (1989), the first movie of the post-Soviet era with Viktor Tsoy, soloist of the famous Kino band, in the lead, and took home the Golden St. George for best film at the Moscow International Film Festival in 2019 and the Grand Prix in Warsaw’s Film Festival.

The topics discussed are synchronistic to many countries where people undergo similar trials by age 40. The international jury saw that, yet it seems what has won the jury’s hearts is the director’s guts to call a spade a spade in an overly tolerant modern society.

According to Russia’s Kinokultura critics, the film centered on the totally disoriented generation.

“As a child, you’ve been raised with a set of values. Then the system changed. Some went along and changed their values. But some others felt lost and perplexed. These opening lines – uttered at the training sessions for personal development at the very beginning of the film – introduce one of the main themes: the predicament of the post-Soviet generation caught between the fading values of the recent past and the newly constructed ones shaping their future,” reads the review.

Sharipov’s “The Secret of a Leader” (2018) won the Golden St. George For Best Film at the Moscow International Film Festival in 2019. Photo credit: Kinopoisk.

The hero goes through a transformation entailing a chain of moral choices, making the story of his success morally ambivalent, if not outright criminal.

In 2020, Sharipov released “18 Kilohertz” about the heroin epidemic among teenagers in the late 1990s in Almaty. The film won the Grand Prix at the Warsaw International Film Festival (2020) and Best Film for Youth at the Cottbus International Film Festival (2020).

Sharipov continued the theme of teenage drug addiction in the 2022 film “Scheme.” It took the Grand Prix in the International Berlin Film Festival’s Generation 14plus section.

Both films are not only made for auteur festivals but also facilitate a conversation between parents and their teenage children, allowing both sides to hear each other out.

According to Sharipov, teenagers do not discuss many taboo topics because they anticipate the adult’s reaction. He believes it is important to provide a teenager with a choice.

“It is quite easy to find oneself in a predicament similar to that of the film’s main protagonist. Human freedom is extremely difficult to limit. My film is about making a choice. It is critical that a teenager makes that choice himself and understands that he has one,” Farkhat Sharipov said in an interview with The Steppe.