ASTANA – Kazakhstan has witnessed a remarkable surge in its pop music scene over the past few years, with a new wave of talented artists emerging and captivating audiences. In a world where music has the power to connect people from diverse backgrounds and make a change, the Kazakh band Ninety One has emerged as a beacon of cultural expression and social activism.

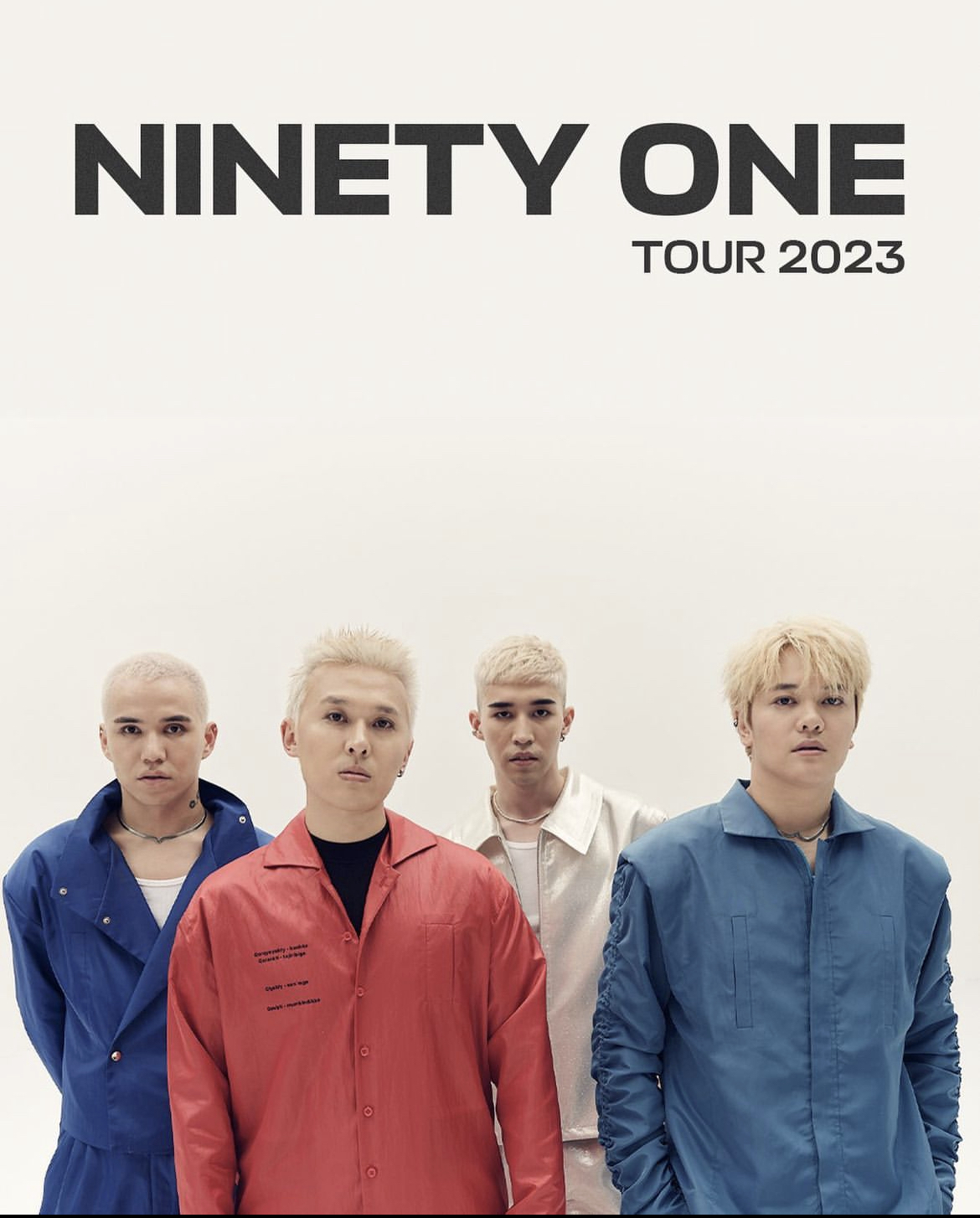

From L to R: ZaQ, Bala, Alem and Ace. Photo credit: Spotify

Through their unique blend of pop, hip-hop, and Kazakh sounds, the group has captivated audiences and embraced the power of language to advocate for change. Breaking stereotypes and breaking barriers, Ninety One has become a voice for Kazakhstan’s youth, using music to challenge societal norms and spark conversations on crucial issues.

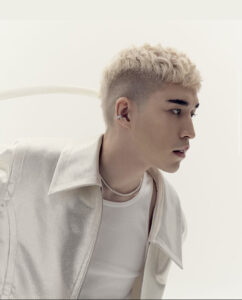

Dulat Mukhametkaliyev, 27, who performs under a stage name, ZaQ, is a native of Semei in eastern Kazakhstan. Photo credit: kprofiles.com

Created in 2014 as part of the K-Top Idols project, a singing competition looking for talented individuals who could form a band, the Ninety One includes four singers – ZaQ (Dulat Mukhametkaliev), Ace (Azamat Ashmakyn), Alem (Batyrkhan Malikov) and Bala (Daniyar Kulumshin). Azamat Zenkaev, under the nickname of A.Z., left the group in 2020.

Ace, 29, passed an internship at Korea’s leading SM Entertainment agency before joining the band. Photo credit: ntk.kz

Their band name represents the year when Kazakhstan gained independence – 1991.

Divided public perception

The band debuted in September 2015 with the “Aiyptama” (Don’t Blame Me) song, which topped the charts for nearly 20 weeks. The music video now has 4.5 million views on YouTube.

Bright costumes, makeup, and long and colored hair is not something one would associate with a Kazakh male band back in 2015, but Ninety One broke all norms and barriers. For a society ripe with patriarchal norms, the welcome to the band was not cheerful.

The group’s first tour was disrupted in nine of Kazakhstan’s regions, either canceled at the last moment without warning or due to protests against the band. The singers were criticized for their “non-traditional” looks.

Alem is the stage name for Batyrkhan Malikov, 30. Photo credit: Alem’s Instagram page

“We saw that coming. I knew we would be subject to scandals and that it would be challenging. But I realized we would not go further without pushing the boundaries, because at the moment show business in Kazakhstan reached its ceiling. The show business has become too localized, and that bothers me because we are a free country. We should see the bigger picture, and everyone knows that,” said former producer Yerbolat Bedelkhan.

Despite the controversy, tickets for their concerts are sold out in minutes or hours, with a rising fandom in each Kazakh city, who call themselves Eaglez. There are more supporters than opponents, even though both are primarily young people.

“If we look at things in general and try to give a rough classification to our young people, we will see two major groups – the first is the urbanized youth who are raised in the city. This is quite new for Kazakhstan, because previously urban citizens were mostly Russian-speaking. But starting from the 2000s, there’s been a new urban generation whose parents moved from the rural areas,” said sociologist Serik Beisembayev in a documentary about the band called “Men Sen Emes” (Face the Music).

Bala, or Daniyar Kulumshin, 25, has a passion for singing and music since childhood. Photo credit: Bala’s Instagram page

“On the other hand, there are young people who are very traditional, which is more common for Kazakh-speaking regions. They are the ones who are now promoting traditional values in the society,” he said, adding that the Ninety One band is the “acid test” to which a young person belongs.

Fresh air in Kazakh show business

Ninety One has been a breath of fresh air for the Kazakh show business, which rarely had any diversity when it comes to how the singers look or what they sing.

In one of his interviews, Bala noted that Kazakh show business predominantly comprises the adult generation. This has changed with the band.

“You could become an artist only if you were an adult. And there was no Kazakh content on the internet. There was no youth on television either – nothing new or fresh. From the moment I was born until I joined the band, nothing had changed,” said Bala, who was just 17 when the group debuted.

Rise of the Kazakh language

While many people see similarities with K-Pop, a distinct feature stands out about Ninety One – their motivation to promote the Kazakh language.

A screenshot from the “Taboo” music video ft. another popular music band Irina Kairatovna. The lyrics of the song has references to acute social problems in the country and to George Orwell.

In a 2021 interview with the BBC, K-pop expert Professor Lee Gyu-tag said Q-pop was deemed a “tool to construct national culture,” while K-pop is “more of a cultural product driven by private companies.”

Ninety One has been instrumental in reviving and popularizing the use of the Kazakh language in contemporary music. By doing so, they aim to inspire pride in their language and encourage young Kazakhs to embrace their roots.

“As a child, I couldn’t simply enjoy a nice show with cool music in my own language,” said ZaQ.

The group announced the release of the new album “Gap” on July 7. Photo credit: Ninety One Instagram page

According to Yerbolat Bedelkhan, who was the band’s producer until 2022, the Kazakh language is an essential element of the self-identification of Kazakhs. Speaking at an event last month on creative industry development, Bedelkhan said the language is a code that carries the national and cultural values of the people.

“We must produce thousands of hours of Kazakh content every day. Then other countries will pay attention to us. When I created Ninety One, many started following our example from countries such as Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan,” Bedelhan.

Ninety One reflects how the entire nation is trying to break free from the Soviet past.

Promoting the use of the language goes hand in hand with how people are trying to recall their national identity. After 70 years under the Soviet regime, which completely suppressed national identities, finding it now is a long process.

“[I want] more soul, more truth. Because when I listen to an artist, I feel he is communicating with me. That kind of music changes me and my outlook on the world. I can become a completely different person after listening to an album, and that’s the power of music. It’s a time when you need to say something to people,” said Zaq in the group’s May 2022 interview with Elle.

It has been 31 years since Kazakhstan gained its independence, yet the push to embrace national identity has only recently been reemerging. People, especially younger generations, are more keen to speak the Kazakh language, opt for outfits with traditional elements, read Kazakh literature, and remember the tragic pages of Kazakh history, such as Asharshylyq (famine) and Stalinist repressions.

The importance of nurturing cultural and historical identity and youth education has been the focus of President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s address at the second National Kuryltai meeting on June 17 in Turkistan.

Using music to advocate for children’s rights

On May 16, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) appointed members of the Ninety One as its National Goodwill Ambassadors. They will use their voices and prominence to advocate for children’s rights, particularly children’s mental well-being and online safety.

From L to R, Batyrkhan Malikov (Alem), Dulat Mukhametkaliyev (ZaQ), Azamat Ashmakyn (ACE) and Daniyar Kulumshin (Bala) during the public event when the group was announced UNICEF’s Goodwill Ambassadors. Photo credit: UNICEF/ RuslanKarsamov

“Music connects people, and we hope that with our music, we can reach people’s hearts and minds and raise awareness about the most critical issues facing children in Kazakhstan,” said group member Ace.

“We know how it feels when you are bullied and public opinion about you forms on the basis of your outfit alone. We know how difficult it is to cope with bullying. Now, we have a chance to support UNICEF programmes and help children overcome these problems,” said Bala.

Arthur van Diesen, UNICEF Representative to Kazakhstan, said Ninety One has “enormous youth appeal.”

“Music gives hope to people. Ninety One incorporates a new generation of Kazakhstan’s artists with enormous youth appeal. We share similar values, and I am confident they will be wonderful National Goodwill Ambassadors for UNICEF,” he said during the public ceremony.

Below is the music video of Ninety One’s popular “Men Emes” (Not me) song, which says, “Holding my flag tight in my hand, I went through hot and cold.”