ASTANA – Kazakh national music kui, traditionally played on dombra or kobyz, captivates fans from all over Kazakhstan. The music has become so popular that it prompted the Kazakh Ministry of Culture and Sport to organize a festival of traditional music Shertpe Kui that took place in Almaty during Dec. 1-3, promoting the music genre that forms an important part of the Kazakh cultural heritage.

The winner of the festival among 45 participants became Madiyar Suleimenov earning the grand prize of 1 million tenge (US$2,130). Photo credit: press service of Kazakh Ministry of Culture and Sport

The three-day musical event took the viewers on a journey through the rhythms of the Kazakh world. The festival was composed of two rounds and featured young dombra players aged 16-35 who competed performing five works of the traditional shertpe kui school and one modern composer’s melody. The winner of the festival among 45 participants became Madiyar Suleimenov earning the grand prize of 1 million tenge (US$2,130).

The kui is a traditional Kazakh piece of music that is not just a set of rhythms, it takes one back to the remote past where Kazakh nomads expressed through it their liberty, joy, as well as misery and daily worries. Music was pervasive in everyday Kazakh life: it could be heard during national holidays, as part of rituals and ceremonies, like weddings or the Nauryz (new year) celebration.

The word “kui” (küy) in the Kazakh language also correlates with the notions of “mood” and “condition.” From this one can understand the psychologism and the nature of the genre intended to reflect all moves of the human soul.

Kazakh traditional art of dombra kui was included in the UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2014.

Dombra, a traditional two-string Kazakh instrument remains the main instrument to play kuis. Kuis on dombra are divided into two major categories: shertpe kui and tokpe kui, depending on the flow of the music.

Shertpe kuis are often low-pitched and played on dombra with the tips of the fingers of the right hand. While tokpe kui is performed with an emphasis, with a full swing of the right hand which gives the sound a flowing nature.

The Limp Kulan legend – the power of delivery of Kazakh kui

The beauty and ancient history of Kazakh kui has always fired the imagination of the people. Here is the captivating story on the delivery power of kui that lies in the performer’s mastery.

“Aksak kulan” (The Limp Kulan) is a Kazakh folk kui played by Ketbuga, based on the legend, the events of which are related to the death of Jochi, the son of Genghis Khan, the emperor of the Mongol Empire.

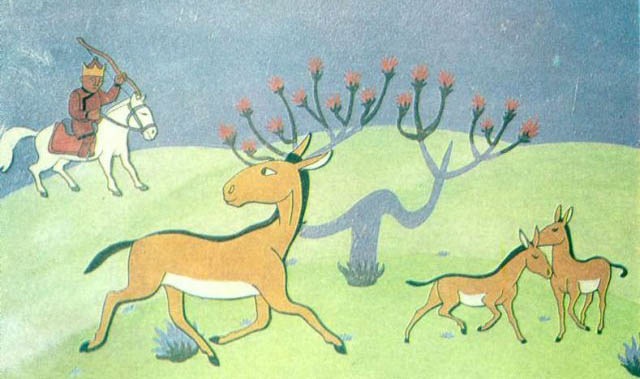

A frame from the 1968 animated movie “Aksak kulan.”

According to the legend, Jochi was keen on archery for kulans. Once he chased a herd of kulans so deep into the woods, that his group was left far behind. The leader of the herd, known as the Limp Kulan suddenly turned around and attacked Jochi, who fell off the horse, injured his neck, and died immediately.

None of the retinues dared to deliver the news to Genghis Khan. The father’s heart felt something was wrong and threatened the death penalty for anyone who reported bad news.

Hearing that, wise old Ketbuga zhyrau (kui performer) carved a dombra from a birch tree, strung the strings on it, and came to Genghis Khan’s palace. He did not say a single word. Ketbuga began to play on dombra a sad melody, a kui which told the story of how Jochi died and the Khan understood everything.

The legend has it that after Ketbuga stopped playing, Genghis Khan said “You deserve to die for your sorrowful message, but since you have not uttered a word, your dombra will be punished. Fill the dombra’s throat with lead!”

This is also a story to explain why the Kazakh dombra has a hole in the middle of its body part.

Aleksandr Zatayevich, preserving Kazakh kuis

A treasured period of Kazakh music history including thousands of kuis and songs was preserved and made known beyond Kazakhstan due to the extensive work done by Soviet ethnographer Aleksandr Zatayevich.

Aleksandr Zatayevich (M) has made an enormous effort in recording and preserving the Kazakh traditional kuis and songs. Photo credit: e-history.kz

Zatayevich developed a fascination for the rhythms of old Kazakh kuis and songs after attending the Vernyi (current Almaty) congress of akyns (performers) in 1920. He recorded a handful of songs before deciding to dedicate the next 10 years of his life to collecting and recording the melodies of the steppe.

The result of over 10 years of effort, is the collections “1,000 songs of the Kazakh people” and “500 Kazakh kuis and songs” published in 1931. The latter collection included musical pieces of such remarkable composers as Abai Kunanbayev, Kurmangazy, Birzhan Sal, Zhayau Musa, Dauletkerey, Baluan Sholak, Muhit, Ibrai, as well as notable folk performers as Amre Kashaubayev, Gabbas Aitpaev, and Kali Baizhanov.

In 1931, in his unsent letter to Romain Rolland (French writer), quoted in Kazakhstanskaya Pravda newspaper, Zatayevich wrote “the beginning of No. 482 (Otti-ketti song) reminds the tempo, the thematic development of Beethoven, and the trio of this piece is almost identical to musical formulas of Anton Rubinstein, who certainly could not have known the Kazakh music, and No. 57 – this colorful march of Jochi Khan (the older son of Genghis Khan) is a true musical and archeological piece, worthy of some Stravinsky, and so on,” describing the diversity of Kazakh musical pieces.

Another letter addressed to Zatayevich’s daughter, offers an insight into the author’s first meeting with a well-known Russian writer Maxim Gorky and the story of Zatayevich playing him Kazakh kuis.

“The other day I was at Maxim Gorky’s. He invited me to sit down in a friendly way, but when I just started ‘last year I sent you, in Sorrento, my work ‘1,000 songs of the Kazakh people’’, his eyes widened, a wide smile spread over his face, and he stood up and offered his hand across the table again with the words: ‘I am sorry, I did not hear you! So, you are Zatayevich! You have sent me the most magnificent book, the richest collection of beautiful melodies, which I have shown to many Italian musicians, who in turn admired them!’” wrote Zatayevich.

The author continues in the letter: “Leaving, I expressed my desire to play him my pieces someday, when he extended his hand to the magnificent Bechstein (piano) saying ‘What about now?’ Of course, I happily began playing “Adai” kui and then “Aida-bylpym,” “Ardak,” “Saryarka” – eight to ten pieces in all! He then asked me to come over and play him and his friends more when he gets back from his vacation to Russia in five weeks. I gladly agreed.”