“It is hard to explain what the very name of Abai means to Kazakhs. His cultural significance can remotely be compared to the role which Leo Tolstoy’s work and personality played in Russia’s culture, especially since the two great men lived in the same historical epoch. But even that would not be enough. Because Abai Kunanbayev (1845-1904) literally molded the nation, his life’s impact on the life of Kazakhs was not only artistic or cultural. His impact was moral, civilizational, even legal – he was really his nation’s teacher, from its very tender age to maturity,” says Nikolay Anastasyev, a professor of Moscow State University and the author of the great biography “Abai. The Hard Flight.”

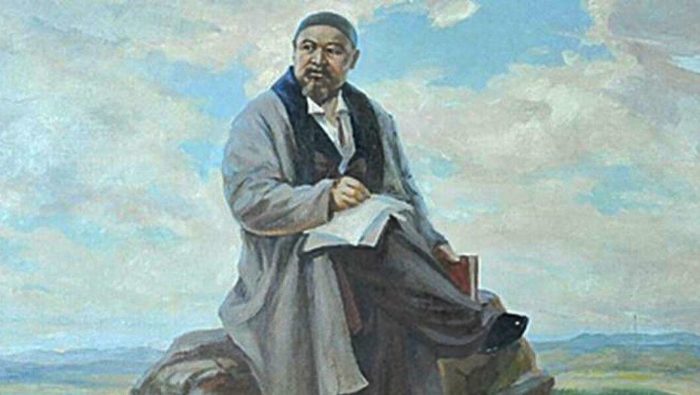

Kazakh artist Nikolai Krutilnikov’s painting “Abay at work” (1923).

One could add here the wise words of the First President of the Republic of Kazakhstan – Nursultan Nazarbayev. Elbasy (Father of the Nation) said that Abai would remain a teacher even for the future generations Kazakhs, because “for every new generation Abai’s legacy will reveal new colors.” No wonder that Abai’s 175th birthday made 2020 “the year of Abai” in Kazakhstan, with more than 500 events planned to mark the anniversary.

One could just quote the encyclopedia saying that Abai Qunanbaiuly (known to tens of millions of Russian-speaking people under a Russified version of his name – Abai Kunanbayev) collected and published the oral legacy of Kazakh folk poetry, that he translated into Kazakh the greatest European poets Goethe and Byron, whose works he first learnt thanks to his mastery of the Russian language. One could add that Abai also translated into Kazakh the works of the greatest Russian poets – Alexander Pushkin, Mikhail Lermontov, Ivan Krylov.

One could roll out this impressive official list of achievements. But that would certainly not be enough for Abai. As Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev rightly wrote in his recent article, Abai created a Kazakh version of a “perfect man”. His life itself became an inspiring example. In that sense, Abai’s achievement can be compared to the achievement of Confucius, “the teacher of a thousand generations” of Chinese. Confucius also made the image of a “perfect man,” “a man of integrity” the central pillar of his life’s work.

Dmitry Babich

“Work and knowledge are better than any wealth, because wealth can be wasted and skills stay with you.” “Believe in yourself, pull yourself out of the daily routine by your own effort.” These are the quotes from Abai’s work, which president Tokayev chose for his speech, noting that Abai’s “perfect man” is exactly what the English people mean when they call someone “a man of integrity.” In Tokayev’s words, what makes a “man of integrity” is primarily the feeling of great social responsibility.

“Social responsibility” – in Abai’s case these are definitely not empty words. Indeed, the lifespan of Abai (1845-1904) fits inside the lifespan of Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910). But the Kazakh member of this great pair, however, lived a much shorter life and was constrained by a number of circumstances: marriage by his father’s choice, the need to support the families of dead relatives, combining Islamic studies in Eastern languages and an education in Russian… Social responsibility – throughout all of Abai’s hard life. And even his death was predetermined by concern and grief for others: Abai died after the deaths of his two beloved sons.

Still, there is still a certain similarity between Abai and Tolstoy: scions of noble families, they both loved their native land, admired its nature and tirelessly toiled at improving themselves and the people around themselves – morally, artistically, culturally. But Abai felt special responsibility. He had to remake his people, the Kazakhs, predicting the hardships that would befall them in the 20th century. He had to open his kind and talented nation of nomads to the world – and bring the world to them via learning and open attitudes. And, what is most tragic, he had to do it in a brief period of time (he did not live to the age of 60, while Tolstoy lived to 82). Abai died in 1904, right on the eve of Kazakhstan’s entering (together with all of the Russian Empire) the period of tragic revolutions. Abai had so much on his hands – and he had to do all that work inside an empire where his people was not a dominant group.

Moreover, saving and protecting his people, Abai had to combine and reconcile. He had to put up with things which seemed irreconcilable. Islam and Christianity, respect for the tradition of the ancestors and learning new trades and sciences from neighbors, diplomacy with the czar’s viceroys and tactful attitudes in settling disputes inside the Kazakh society itself. Abai inherited the position of the judge from his father, but he was also elected to that position by the people’s will and trust. Abai had to learn it all, from the Shariah law and tribal traditions to European laws and modern sciences. He learned so much, that this may be the reason why he was so demanding towards his nation. “Humans are led astray by laziness and absence of action.” “Learn how to toil the land from the Uzbeks, learn sciences from the Russians, learn to fight from the Nogays” – Abai was never tired of urging his people to act and imbibe knowledge, not to stay idle. “If we had only listened to him, we could have avoided so many of the misfortunes that befell us in the 20th century,” says Olzhas Suleimenov, Kazakhstan’s leading poet and public figure, a fighter against the ecological disaster that was produced in Kazakhstan by Soviet nuclear tests.

There were times when it seemed that Abai’s tradition was nearing extinction. When his three sons died, when daughters became victims of Stalinist repressions, when Alash Orda, a Kazakh nationalist party based on Abai’s ideals, was prohibited in the conditions of a communist monopoly on power in the 20th century… But better times returned, like a spring returns to the Kazakh steppes after a harsh and windy winter – and the interest for Abai’s legacy grew again.

“Every new epoch reveals new sides of Abai’s greatness,” Kazakhstan’s Elbasy (Leader of the Nation) Nursultan Nazarbayev said about the great Kazakh poet. “Abai will always live and change together with his people.”

“The Words of Instruction” – series of moral treatises from Abai – this major achievement of Abai’s life is becoming indispensable for Kazakhstan’s citizens, despite the fact that some parts of these instructions are actually very critical of the writers Kazakh contemporaries.

“The great poet criticized his compatriots’ underachievements, but while doing that, he had one goal in his mind – to lead his people to prosperity and to recognition I the entire world,” President Tokayev wrote in his article “Abai and Kazakhstan in the 21st Century.” Now, as the President put it, other nations have familiarized themselves mostly with the economic achievements of Kazakhstan. “Now, let’s put the question this way” why don’t we show the world our culture and the beauty of Kazakh lifestyle – via the example of Abai?”

The author is a Moscow-based journalist with 30 years of experience of covering global politics, a frequent guest on BBC, Al Jazeera and RT.