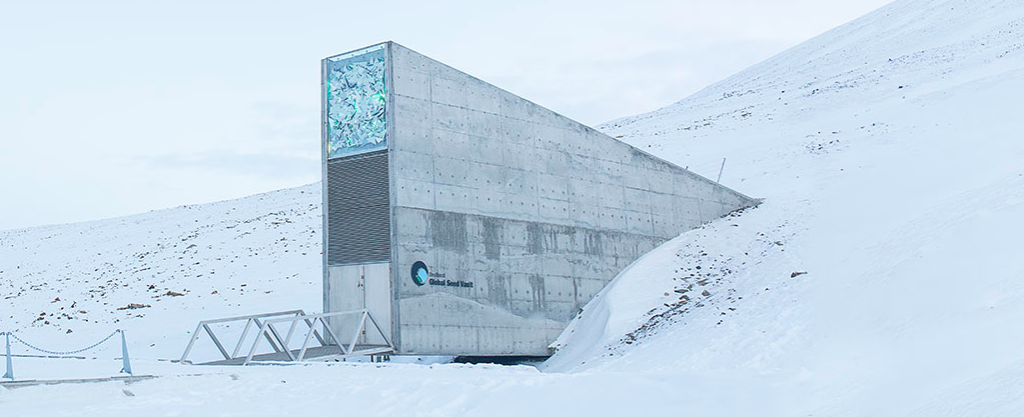

ASTANA – Svalbard is home to approximately 2,500 people and one million types of seeds in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, a secure bank preserving copies of plant seeds held in gene banks in Central Asia and worldwide. In an interview with The Astana Times, seed vault coordinator Åsmund Asdal explained why a vault on the side of a mountain between Norway and the North Pole is the world’s most important insurance policy.

Constructed in 2008, the seed vault is managed under the Norwegian government, Global Crop Diversity Trust and Nordic Genetic Resource Centre. The hope is society will never have to use it, much like home insurance holders hope to never use their policy. Lebanese scientist Mahmoud Solh’s seed-collecting journey throughout Central Asia, for example, developed into Syria’s International Centre for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas (ICARDA) seed collection. Following the 2011 Syrian civil war, some of the seeds were stored in Svalbard for safety until ICARDA was reestablished elsewhere and requested to withdraw its 90,000 seeds.

“The ICARDA case really showed the importance and usefulness of the seed vault,” said Asdal on Svalbard’s first withdrawal. “The fact that ICARDA had copies in the vault made them able to restore gene banks in Morocco and Lebanon and to continue their important work in plant breeding and research for improving food production.”

The vault’s egalitarian design and free-of-charge storage policy has also created a unique world peace zone where rival nations’ seeds sit beside one another. After all, food supply protection concerns everyone.

“Conservation of plant genetic resources is needed for future food production,” he noted. “All countries need food and are concerned about food supplies for their populations… No countries are self-sufficient in genetic resources, so all governments understand that international cooperation is needed.”

Still, Asdal finds the greatest threat to all seed banks is a lack of funds, followed closely by war and natural disasters. Many politicians in both developing and developed countries have yet to act on genetic resource conservation and availability for plant breeding and future food production, he said. The team behind the vault has launched public awareness campaigns to convince governments and gene banks to make vault deposits, with 76 depositor institutes having made theirs, and he hopes to see deposits from Kazakhstan’s gene banks in the future.

“The best way for citizens to encourage the conservation of genetic resources in their countries is by urging governments to allocate resources, by donating seeds of old varieties and landraces to national gene banks who can then deposit copies in the vault and, as consumers, by requesting food products from a diversity of plants,” he said.

At Svalbard, 1.64 million seeds originate from Tajikistan, 1.13 million from Kazakhstan, one million from Uzbekistan, 345,024 from Kyrgyzstan and 308,232 from Turkmenistan. Seed preservation, however, is not a numbers game; instead, it is a diversity one. A 2009 conservationist report “The Red List of Trees of Central Asia” found that Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan have more than 300 wild fruit and nut trees, 44 of which are critically endangered, threatened or vulnerable due to climate change, timber felling, overgrazing, pests and diseases.

“Your region is extremely rich in genetic resources and it is important that these resources are conserved for the future,” said Asdal on Central Asia’s contribution to agricultural diversity. “As of today, there are deposits in the vault from Uzbekistan comprising barley, sorghum, wheat and maize and from Tajikistan comprising barley and wheat.”

The idea behind every gene bank, that seed collection and a greater understanding of crop diversity could prevent famines, was born in the Soviet Union. Raised during severe famines, Soviet scientist Nikolay Vavilov dedicated his life to ending famine in Russia and the world, a pursuit that resonates in Kazakhstan given its 1930-1933 famine that claimed 1.5 million lives. On his visit to Kazakhstan, he identified the wild apple Malus sieversii as the ancestor of all cultivated apples grown and eaten worldwide and added its seed to St. Petersburg’s Vavilov Institute Gene Bank, one of the first in the world.

“Vavilov’s efforts and achievements have been crucial for the development of gene banking and for the conservation of plant genetic resources around the world. He was the pioneer and we are proud to have the seed vault as a facility following his ideas,” said Asdal.

To learn more about the vault, one can visit www.seedvault.no and explore its seed portal at www.nordgen.org/en/global-seed-vault/search-seed-vault.