ASTANA – Archcode Almaty, a research project to conserve the former capital’s architectural identity, seeks to preserve what “we will pass on to those who will live in the city after us,” said co-founders Adil Azhiyev and Anel Moldakhmetova in an interview with The Astana Times.

Azhiyev is an architect and researcher specialising on the strategic city development. Moldakhmetova is a researcher, Light+Space urban project producer and co-founder of Cityzen Space, which specialises in strategic communications. Together, they seek to create an active professional community engaged in architectural heritage preservation, involving the city administration, developers and the wider public.

“An urban dialogue is, after all, a dialogue,” they said. “It is a discussion among different stakeholders of the city – citizens, businesses, the city administration, cultural institutions and non-governmental organisations. For example, it involves the practice of compulsory public hearings when important decisions on buildings, public spaces and natural resources are made, not ‘for show’ but for finding optimal solutions and taking into account the opinions of all interested parties.”

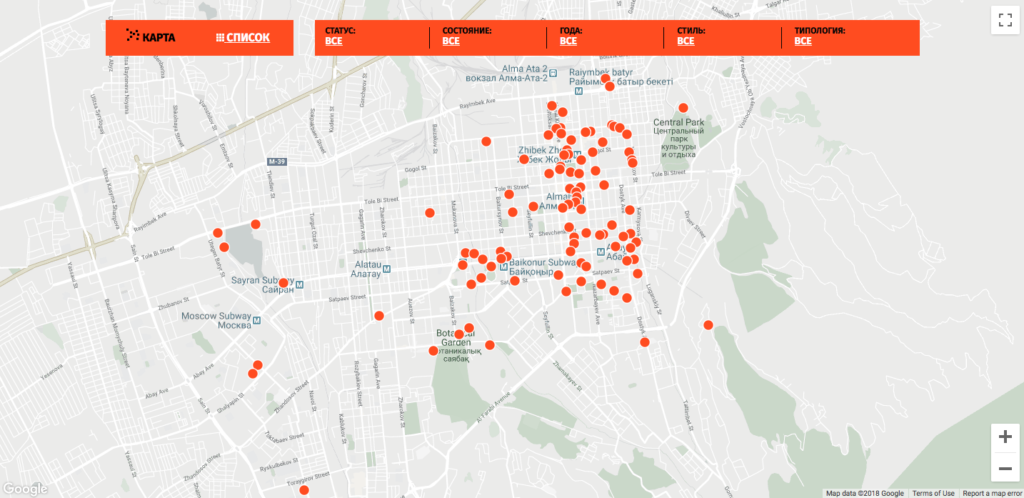

To facilitate the dialogue, the duo has compiled an impressive digital catalogue of the city’s 100 most significant buildings on www.archcode.kz/objects/map. Additional awareness-raising efforts include conducting open architectural walks and lectures with international urbanism experts. Most recently, they organised a series of master classes on archiving architectural landscapes Oct. 18, 21 and 25 at Tselinny Almaty’s centre of contemporary culture.

“An event which garnered the most resonance was the Architectural Code of Almaty pop-up museum, which was notably held in the former government building, now Kazakh-British Technical University. We received very emotional feedback from those who, prior, had not considered Almaty’s architectural value and who then thanked us for pushing them to reflect on how our architectural landscape is changing and what ought to be preserved,” they said.

Cities’ cultural heritage is important to both study and preserve.

“It is thanks to history and our collective memory that places acquire meaning, uniqueness and context,” said Moldakhmetova.

A brief look at Almaty’s history suggests the many ways in which its architecture is unique in Kazakhstan and Central Asia. Its architecture began taking a distinctive shape in the 1930s by undergoing constructivism, followed by Stalin’s neoclassicism and the Soviet modernism of the 1960-1980s. Many architectural projects were initially carried out by visiting experts from Moscow, after which local designers began to get more involved.

“Local architects managed to give projects a uniqueness by adding façade design, solar protection and natural materials such as Mangystau shell rock and anodised aluminum,” they noted. “Kazakh Soviet-era communist politician Dinmukhamed Kunayev strongly promoted the creation of national architecture, so it was during those years that significant progress was made in shaping the face of the city.”

Azhiyev and Moldakhmetova single out several barriers to preserving architectural heritage. A clear, locally-applicable criteria for assessing its value is underdeveloped, so experts tend to draw on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation’s (UNESCO) broad criteria. He added the city’s culture department lacks the resources to carry out the research necessary for developing its own points of reference.

A lack of transparency and the top-down nature of the procedure for adding monuments to the architectural heritage list are also major hindrances.

“[Often, there is] no clear mechanism for monitoring the quality of building restoration and reconstruction and licensed institutions’ decision making on restoration, reconstruction and demolition projects,” they noted.

“Society is not engaged in these processes. In fact, people only begin to write requests to the culture department when a specific building is already under the threat of demolition, at which point it is difficult to effect change,” they added.

Getting involved in preserving one’s urban cultural heritage is a straightforward, if not easy, process.

“Start by exploring the history of your city’s cultural heritage,” said Azhiyev and Moldakhmetova. “Find a circle of like-minded people via social networks and events in order to begin discussing the fate of the architecture. Then, disseminate information on the value of the city’s architecture by working with the press and produce articles on these issues. Finally, do not remain indifferent to historic buildings which are being demolished or poorly restored – write appeals or petitions to your department of culture and highlight these issues in local and international media.”