“Olzhas! Olzhas!” the crowd roared whenever their hero took the stage. A year ago, Olzhas Suleimenov, a 50-year-old poet, founded a protest movement in Kazakhstan to stop the Soviets from testing their nuclear weapons in the Kazakh Desert.

Now his admiring countrymen carry him on their shoulders as they march, and they name their infant sons after him. They elected him to the Congress of Peoples’ Deputies in Moscow. Suleimenov named the protest movement “Nevada-Semipalatinsk” to link the people in both the U.S. and U.S.S.R. who have suffered the effects of nuclear testing.

In May, the Nevada-Semipalatinsk movement held a meeting in Kazakhstan and invited 300 foreigners, including 150 doctors, to join them and visit the desert test site near Semipalatinsk. I was one of three doctors who attended from Canadian Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War. The others were Dr. Alex Bryans, the president of CPPNW, and Dr. Ed Crispin, a general practitioner from Guelph.

We met first in Alma Ata for a conference addressed by scientists and physicians, but taken over by Kazakhs – herdsmen, poets, construction workers and veterans. They grabbed the microphones and became so excited and shouted so rapidly the translation was either garbled or drowned out. Occasionally the interpreter would say cryptically “that seemed to be an in-group debate”.

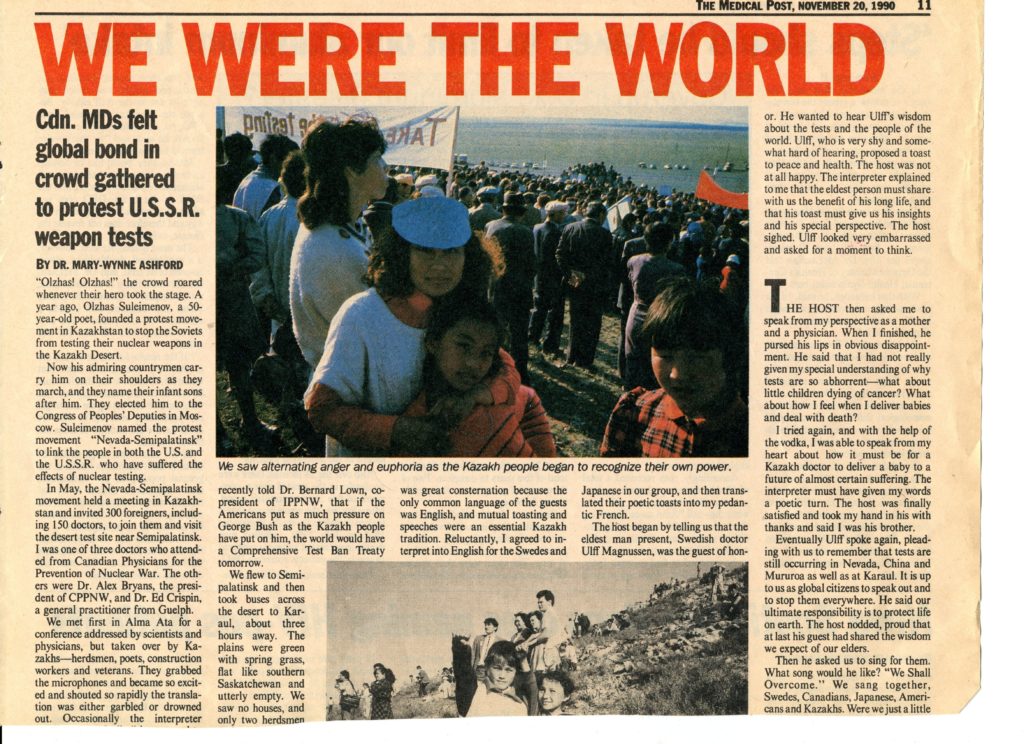

I have travelled in the Soviet Union with International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War four times before, but I have never experienced such a gathering. Posters had caustic message like “Let the Generals build their summer houses on the Test Range!” Gone were the passive faces and the clichés about being a peace-loving people. Instead, we saw alternating anger and euphoria as the people began to recognise their own power.

The Soviet tests have caused widespread radioactive contamination and appear to be continuing to cause cancers and birth defects at a horrific rate. I say “appear to be” because what statistics there are secret and even their doctors don’t know the epidemiologic evidence. Some speakers called for strikes and independence for Kazakhstan, but the general feeling was that what was needed was justice, not secession.

The protests have succeeded in stopping all Soviet tests since last October – a year now. Mikhail Gorbachev recently told Dr. Bernard Lown, co-president of IPPNW, that if the Americans put as much pressure on George Bush as the Kazakh people have put on him, the world would have a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty tomorrow.

We flew to Semipalatinsk and then took buses across the desert to Karaul, about three hours away. The plains were green with spring grass, flat like southern Saskatchewan and utterly empty. We saw no houses, and only two herdsmen and a flock of sheep in the whole day’s journey.

At Karaul, there was a demonstration on a hillside, with hundreds of people holding banners and waiting for our arrival. Again, the passionate speeches and the shouts for Olzhas Suleimenov, their leader. I walked up the hill and looked back over the majestic foothills and out to the mountains 30 km away where the tests are done. We had seen a film of a test carried out inside the mountain. The blast lifted the whole side of the mountain into the air and dropped it back in a cloud of dust.

The demonstration went on all afternoon. We were absorbed into the crowd of Kazakhs, some on horseback, many carrying children. The Kazakhs are handsome Mongolian-looking people with long straight noses and tanned skin. A Shoshone Indian man from Nevada looked so much like the Kazakhs he might have been related.

Some of our doctors were wearing film badges to detect radiation. I was trying to clench my nostrils in a vain attempt to minimise breathing, and I avoided sitting in the dust. But we cannot avoid knowing that we are people of the same earth. This desert that is blooming in early spring is my desert, too, and this tragedy is also my tragedy. I am no more special than this Kazakh woman with her child in her arms. Together we must stop the destruction of our planet.

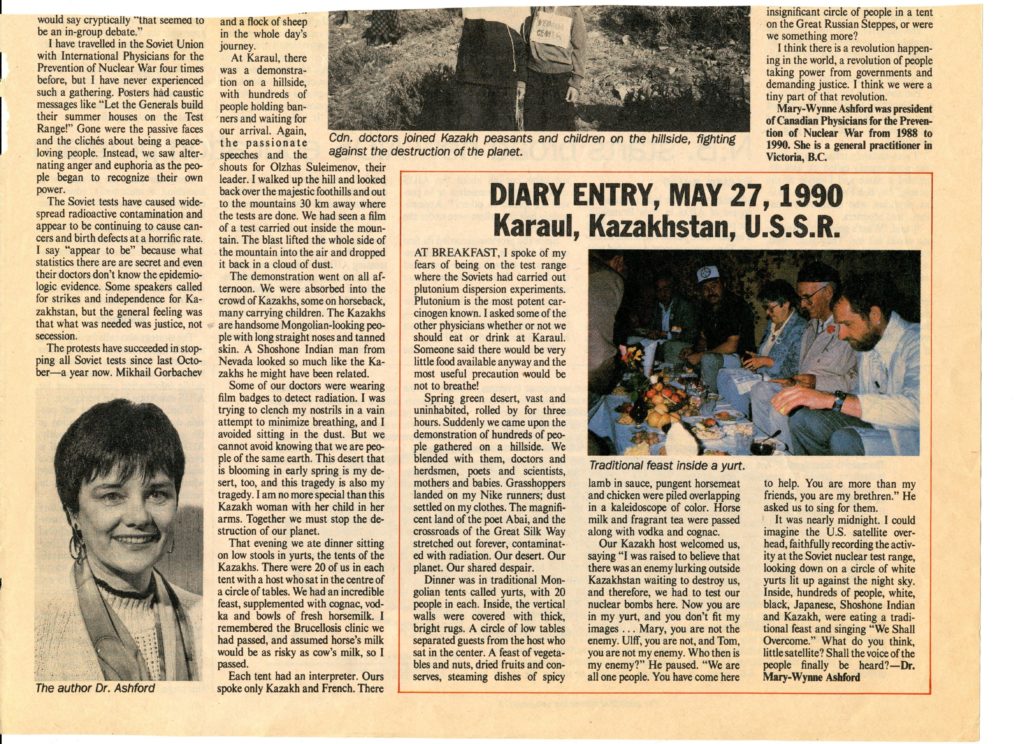

That evening we ate dinner sitting on low stools in yurts, the tents of the Kazakhs. There were 20 of us in each tent with a host who sat in the centre of a circle of tables. We had an incredible feast, supplemented with cognac, vodka and bowls of fresh horse milk. I remembered the Brucellosis clinic we had passed, and assumed horse’s milk would be as risky as cow’s milk, so I passed.

Each tent had an interpreter. Ours spoke only Kazakh and French. There was great consternation because the only common language of the guests was English, and mutual toasting and speeches were an essential Kazakh tradition. Reluctantly, I agreed to interpret into English for the Swedes and Japanese in our group, and then translated their poetic toasts into my pedantic French.

The host began by telling us that the eldest man present, Swedish doctor Ulff Magnussen, was the guest of honour. He wanted to hear Ulff’s wisdom about the tests and the people of the world. Ulff, who is very shy and somewhat hard of hearing, proposed a toast to peace and health. The host was not at all happy. The interpreter explained to me that the eldest person must share with us the benefit of his long life, and that his toast must give us his insights and his special perspective. The host sighed. Ulff looked very embarrassed and asked for a moment to think.

The host then asked me to speak from my perspective as a mother and a physician. When I finished, he pursed his lips in obvious disappointment. He said that I had not really given my special understanding of why tests are so abhorrent – what about little children dying of cancer? What about how I feel when I deliver babies and deal with death?

I tried again, and with the help of the vodka, I was able to speak from my heart about how it must be for a Kazakh doctor to deliver a baby to a future of almost certain suffering. The interpreter must have given my words a poetic turn. The host was finally satisfied and took my hand in his with thanks and said I was his brother.

Eventually Ulff spoke again, pleading with us to remember that tests are still occurring in Nevada, China and Mururoa as well as at Karaul. It is up to us as global citizens to speak out and to stop them everywhere. He said our ultimate responsibility is to protect life on earth. The host nodded, proud that at last his guest had shared the wisdom we expect of our elders.

Then he asked us to sing for them. What song would he like? “We Shall Overcome.” We sang together, Swedes, Canadians, Japanese, Americans and Kazakhs. Were we just a little insignificant circle of people in a tent on the Great Russian Steppes, or were we something more?

I think there is a revolution happening in the world, a revolution of people taking power from governments and demanding justice. I think we were a tiny part of that revolution.

Diary entry, May 27, 1990

Karaul, Kazakhstan, U.S.S.R.

At breakfast, I spoke of my fears of being on the test range where the Soviets had carried out plutonium dispersion experiments. Plutonium is the most potent carcinogen known. I asked some of the other physicians whether or not we should eat or drink at Karaul. Someone said there would be very little food available anyway and the most useful precaution would be not to breathe!

Spring green desert, vast and uninhabited, rolled by for three hours. Suddenly we came upon the demonstration of hundreds of people gathered on a hillside. We blended with them, doctors and herdsmen, poets and scientists, mothers and babies. Grasshoppers landed on my Nike runners; dust settled on my clothes. The magnificent land of the poet Abai, and the crossroads of the Great Silk Way stretched out forever, contaminated with radiation. Our desert. Our planet. Our shared despair.

Dinner was in traditional Mongolian tents called yurts, with 20 people in each. Inside, the vertical walls were covered with thick, bright rugs. A circle of low tables separated guests from the host who sat in the centre. A feast of vegetables and nuts, dried fruits and conserves, steaming dishes of spicy lamb in sauce, pungent horsemeat and chicken were piled overlapping in a kaleidoscope of colour. Horse milk and fragrant tea were passed along with vodka and cognac.

Our Kazakh host welcomed us, saying “I was raised to believe that there was an enemy lurking outside Kazakhstan waiting to destroy us, and therefore, we had to test our nuclear bombs here. Now you are in my yurt, and you don’t fit my images… Mary, you are not the enemy. Ulff, you are not, and Tom, you are not my enemy. Who then is my enemy?” He paused. “We are all one people. You have come here to help. You are more than my friends, you are my brethren.” He asked us to sing for them.

It was nearly midnight. I could imagine the U.S. satellite overhead, faithfully recording the activity at the Soviet nuclear test range, looking down on a circle of white yurts lit up against the night sky. Inside, hundreds of people, white, black, Japanese, Shoshone Indian and Kazakh, were eating a traditional feast and singing “We Shall Overcome.” What do you think, little satellite? Shall the voice of the people finally be heard?

Mary-Wynne Ashford was president of Canadian Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War from 1988 to 1990 and was a general practitioner in Victoria, B.C.

Originally published in The Medical Post on Nov. 20, 1990. Reprinted with permission from the author, Dr. Mary-Wynne Ashford.