ASTANA – What is behind a global social enterprise? What are the trends and challenges in social entrepreneurship? What lies at the core of socially-driven activities?

The British Council, in partnership with Chevron and the Atameken National Chamber of Entrepreneurs, hosted a forum in the capital Jan. 31 to address social entrepreneurship as a new model of sustainable social change. Launched in 2013, the forum attracts entrepreneurs and representatives of state bodies and national companies.

The British Council sees social enterprise as a business with the mission to improve people’s lives and solve ecological and social issues. Business profit is used to tackle social issues.

The role of an enterprise should be considered in light of sustainable growth and job creation defined in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report and United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), said British Council in Kazakhstan Director Jim Buttery. He also addressed how an enterprise can contribute to Kazakhstan’s ambitious national development challenges.

“Yesterday – creative enterprise, today – social enterprise. And for me this is a fascinating area. It is an area where the U.K. has a story to tell and experience to share. It is also an area where in addition to making profits through business, you can contribute value to society. Either social in this case or creative, you enrich society in different ways whilst making money. That feels like a win-win,” he said.

The social enterprise sector has been actively evolving in the U.K. for 20-25 years.

“We describe social enterprises as businesses that are set up to trade and to tackle social problems, improve communities and people’s life chances or their environments. They make their money from the sale of goods and services in European markets, but they are reinvesting their profits back into the business and the local community as business profits and society profits. These businesses we now see in the U.K. are all along high streets and operating in almost every single industry sector you can think of,” said British Council global social enterprise advisor Juliet Cornford.

Such businesses are driven by a social purpose that lies at the heart of that business.

“Importantly, they’re generating the majority of their income through trade and revenue mainly from the sales of goods and services. It is not about grant dependency. Many enterprises in the U.K. still have some grants in activities in their turnover. In the U.K., we try and place a benchmark on a minimum of 50 percent. Many enterprises are 100 percent self-financing, but for those that are still evolving and developing we try and encourage them to reach 50 percent. There may be a mixture of income,” she noted.

Social enterprises, autonomous of states and governments, are majority owned by their stakeholders.

“Many social enterprises, for example, are oriented towards [tackling] disability. You may find people on their boards or their governance structures who have disabilities. Social enterprises always aim to be open and transparent,” said Cornford.

The sector is growing and developing. According to recent results, there are now 70,000 social enterprises in the U.K. which account for 5 percent of all businesses. They contribute 25 billion pounds (US$35 billion) to the economy and employ more than a million people.

“And I think the message here is this is no longer a fringe activity. This is making a mainstream contribution to the economy and to the employability of people. Social enterprises are now operating in almost every single industry, from education and housing to transport and manufacturing,” she added.

Social enterprises are not just making a financial contribution, but are working with a diverse community.

In Kazakhstan, public procurement has been provided for non-governmental organisations (NGO) since 2005. Grants have also been issued by the grant financing operator since 2016. Financing has increased by 1.5 times compared to the previous year and totals more than 900 million tenge (US$3 million). Rewards are provided to NGOs to solve social problems. The annual Asar (Together) forum is aimed at interaction among the state sector, business and NGOs.

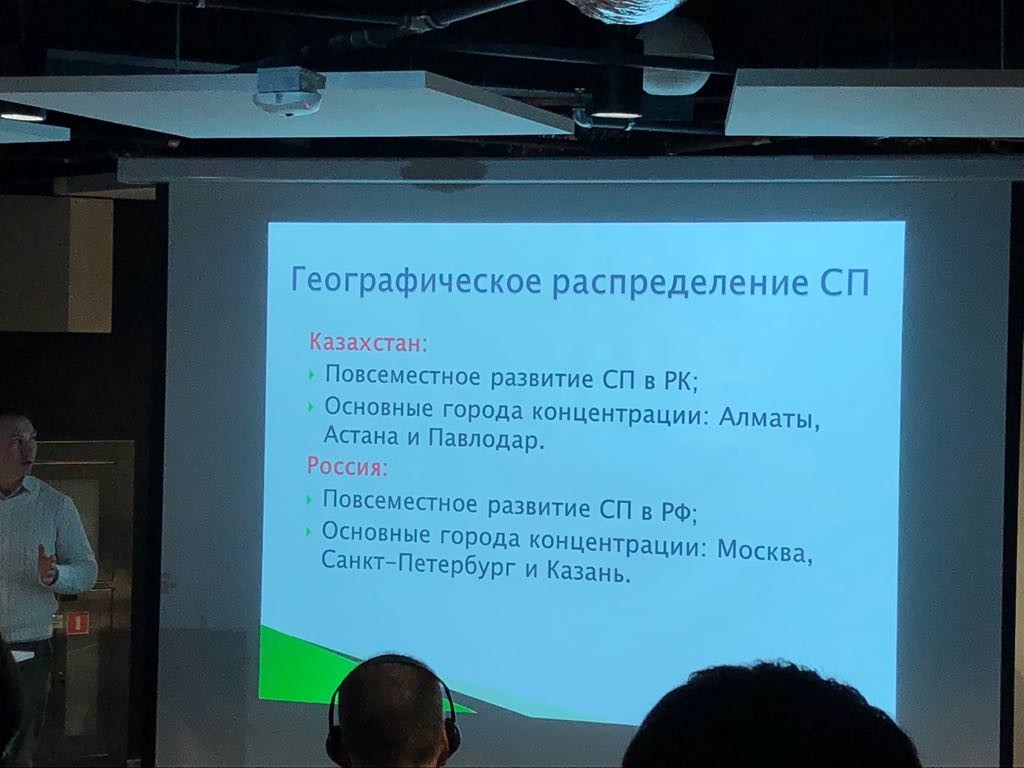

Social enterprise is a relatively new concept in Kazakhstan. Nevertheless, as world practice shows, the model can be widely developed, said Eurasia Foundation of Central Asia project specialist Andrey Bachishe.

“Studies demonstrate low awareness and absence of a universally-accepted understanding of what social entrepreneurship is. People hesitate to invest in business that does not provide fast profits,” he said.

He also pointed to the low level of business culture and legislation that does not provide incentives.

Since 2016, the foundation, in cooperation with Chevron, has released a list of Kazakh social entrepreneurs to raise awareness among NGOs and business and academic communities. Green Tal, a company that trains and employs people from vulnerable social groups, Adal Niet Astana, a social centre assisting older people and a medical centre in the Mangistau region involved in treating and rehabilitating children with physical challenges were named as successful projects.