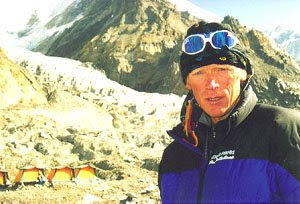

ASTANA – Anatoli Boukreyev, a professional Russian mountaineer from Almaty, Kazakhstan, was the lead climbing guide for the 1996 Mountain Madness expedition to Mount Everest and became widely known for saving climbers during the disaster on the world’s tallest peak. He is portrayed by Icelandic actor Ingvar Eggert Sigurðsson in “Everest,” the recently-released film directed by Baltasar Kormákur.

An experienced high-altitude climber, Boukreyev scaled 10 of 14 mountain peaks above 8,000 metres (26,247 feet) without supplemental oxygen and made 18 successful ascents of 8,000-metre peaks from 1989 through 1997. He died Dec. 25, 1997.

Boukreyev had a reputation in international climbing circles as an elite mountaineer for summiting K2, the world’s second highest mountain, in 1993 and Mount Everest via the North Ridge route in 1995. Eight climbers died in a blizzard May 10-11 the following year while attempting to reach the summit.

According to an April 28 article in The New York Times, 12 people died trying to reach the summit that season, making it the deadliest day and year on the mount until the 2014 Mount Everest avalanche that took 16 lives and the 2015 Nepal earthquake that resulted in avalanches and 18 deaths.

The 1996 disaster gained wide publicity and raised questions about Everest’s commercialisation. Numerous climbers in large and small teams and even some soloists were near the top during the storm, dying both on the North Face and South Col approaches.

Journalist Jon Krakauer published the 1997 bestseller “Into Thin Air” that related his experience while on assignment from Outside Magazine. He was on a team led by guide Rob Hall, four members of which died on the south side.

Boukreyev, whose team lost expedition guide Scott Fischer but no clients, co-authored “The Climb: Tragic Ambitions on Everest” the same year in response to Krakauer’s criticism of his actions during the 1996 disaster.

“The core of the controversy was Boukreyev’s decision to attempt the summit without supplementary oxygen and descend to the camp ahead of his clients in the face of approaching darkness and blizzard,” according to the 1998 “Review of the Climb.”

He defended his decision to move down the mountain ahead of the expedition clients with the argument that someone needed to be at the camp to get them safely into their tents, warmed up and out of their gear. Most importantly, he wanted the climbers to be rested in case a rescue was necessary, which it was, according to Chloe Johnson’s “The Climb” and a June 7, 2012, review of “Into Thin Air.”

“Boukreyev rescued four out of six people lost in the storm and went back up toward the summit the next morning in an unlucky attempt to rescue his guide Fischer, who was missing and found frozen to death,” wrote Johnson.

Boukreyev’s supporters point out that his return to camp allowed him enough rest to mount a rescue attempt and lead several climbers to the safety of the camp when the blizzard subsided around midnight, noted Sherpa Lopsang Jangbu in response to Krakauer’s article on Outsideonline.com.

His detractors said that Boukreyev could have better assisted clients down the mountain if he had simply stayed with them, although every one of his clients survived, including three whom he rescued May 11 after being rested and overcoming hypoxia, reported the article.

“The only client deaths that day were suffered by the Adventure Consultants expedition, led by guide Hall, who lost his own life when he choose to stay and help a client to complete a late summit rather than helping to go down and replenish,” it added.

In 1997, Boukreyev was presented with the David A. Sowles Memorial Award, American Alpine Club’s highest honour, in recognition of his role in rescuing the climbers during the 1996 Everest disaster, according to Americanalpineclub.org.

The climber was killed in 1997 avalanche during a winter ascend of Annapurna in Nepal with Dimitri Sobolev, a cinematographer from Kazakhstan who was documenting the attempt.

Boukreyev dreamt in detail of dying in an avalanche exactly nine months before his death, only he did not know on which mountain it would occur. Others attempted to convince him to take a different path in life but he refused, saying mountains were “his life and work” and that it was too late for him “to take another road,” according to his companion Linda Wylie. She edited and published his memoirs in the 2002 “Above the Clouds: The Diaries of a High-Altitude Mountaineer.”